Members got an extensive review of hemp in food policies in other states, learned five principles regulators wanted recommendations to prioritize, and debated scheduling their next meeting.

Here are some observations from the Wednesday September 21st Washington State Hemp in Food Task Force (WA Hemp in Food Task Force) Meeting.

My top 4 takeaways:

- A previously delayed overview of hemp in food policies outside of Washington covered a multitude of states; artificial and synthetic cannabinoid rules; as well as federal packaging and labeling requirements, prompting several questions.

- On August 17th, Task Force Member Joy Beckerman, Hemp Ace International Founder and Colorado Hemp Works Senior Advisor and Co-Founder, promised to present task force members with what she’d learned about policies in other states and countries. On August 31st, WA Hemp in Food Task Force facilitator Steven Byers acknowledged that Beckerman had been unable to attend. Meetings announced for September 7th and 15th were cancelled.

- Beckerman began with a disclaimer given the rapidly developing nature of the topic. She explained that her presentation had been updated already, but there were sure to be changes and emerging issues.

- Beckerman then addressed “what governs the products that we are making, foods for humans, or dietary supplements” because they were generally referenced or relied upon by laws in other jurisdictions governing hemp in food (audio - 23m, presentation).

- Beckerman shared several parts of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations on good manufacturing practices in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), specifying:

- Foods for Humans (21 CFR 117)

- Dietary Supplements (21 CFR 111)

- Drugs (21 CFR 210 / 211)

- Foods for Animals (21 CFR 507)

- Over-The-Counter (OTC) drugs (21 CFR 330)

- Beckerman emphasized that WA Hemp in Food Task Force members should be especially concerned about 21 CFR 101 covering Food Labeling, and “there are indeed guides out there that the FDA puts out:”

- 21 CFR §101.36 Nutrition labeling of dietary supplements

- Dietary Supplement Labeling Guide

- Food Labeling Guide

- She also claimed it was “impossible” to follow all federal rules, “particularly the [investigational new drug] preclusion” in 21 USC 321(ff)(3)(B).

- Find out more from other commentary on cannabidiol (CBD) and the New Dietary Ingredients (NDI) process:

- Beckerman shared several parts of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations on good manufacturing practices in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), specifying:

- Identifying 27 states which “allow CBD in cosmetics, food, and dietary supplements,” Beckerman reviewed a “patchwork” of “very rigorous” state policies which “require either licensing or product registration.”

- Utah and Hawaii were “states that allow CBD in cosmetics and dietary supplements only.”

- In ten states, CBD was allowed in cosmetics only, but “basically nobody's enforcing anything. It's just…a Twilight Zone world that we are living in,” Beckerman argued. She specified that cosmetics policies were “unclear” on the use of CBD in Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Wyoming. Law enforcement hadn’t been brought to bear, she explained, since questions about “what is the risk to public harm and what are the resources that are available to enforce” hadn’t resulted in many actions until “delta 8[-THC] and synthetic conversion into intoxicating products started flooding the market.”

- Read about Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) research into delta-8-THC policy in other states from June 2021.

- Mississippi and Pennsylvania didn’t allow CBD, although Beckerman added that she’d networked with several “Pennsylvania Department of Ag[riculture] gals” in July, and “they had no idea that Pennsylvania doesn't allow cannabidiol.” Her information listed nine states as generally unclear on the matter.

- Another 13 states had production licensing or product authorization, and 25 had labeling requirements. Beckerman described how Maryland and Oregon only mandated labeling in accordance with federal regulations for products in cannabis dispensaries, but no labeling rules related to “general sale.” She offered to come speak to the labeling work group to dig into the many “rabbit holes” related to the subject.

- 21 states had product testing rules “all over the place,” she noted, a topic the task force was handling through the Concentration and Safety Work Group.

- Turning to “states with age restrictions,” Beckerman shared that:

- Louisiana required a purchaser to be 18 to buy a product containing “any CBD at all,” and required someone buying an “adult-use consumable hemp product” to be 21. Sellers had to attest to having “checks and balances in place on your website,” but oversight was lax (“that's a rule and nobody cares”).

- In Minnesota, “this is mind-blowing, any product containing any hemp-derived cannabinoid” was restricted by law to those 21 and older.

- Oregon had also “defined ‘adult use cannabis item’ requiring 21 years of age for sale in a licensed dispensary,” and were potentially “working on a regulatory framework for 21 and above in other locations outside of licensed dispensaries.”

- “Rhode Island, any ingestible product containing hemp derive[d] CBD” was limited to those 21 and older.

- In Virgina, “any product that contains any detectable THC, you got to be 21.”

- Though inhaled products were beyond the focus of the task force, both Florida and New York restricted inhaled hemp items to those 21 and over.

- Other age-based restrictions her presentation identified involved advertising or restrictions around product types as most “states prohibit products that are attractive to children, contain cartoons, imitate a candy label, or are in the shape of animals, people or fruit:

- 1. California: Advertising or marketing placed in broadcast, cable, radio, print, or digital communications can only be displayed where at least 70 percent of the audience is reasonably expected to be 18 years of age or older, as determined by reliable, up-to-date audience composition data

- 2. Hawaii: Label must include the statement ‘Keep out of the reach of children.’ or words of similar meaning

- 3. New York: Label must include the statement ‘Keep out of the reach of children.’

- 4. Ohio: Label must indicate that consumers should consult a licensed healthcare professional if pregnant, breastfeeding, currently taking medications, or under 18 years of age

- 5. Virginia: For products that contain any THC, the label must state that the industrial hemp extract or food containing an industrial hemp extract contains tetrahydrocannabinol and may not be sold to persons younger than 21 years of age

- 6. West Virginia: Any product containing more than 0.3% of [THC], or more than 0.3421% of tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, must declare ‘NOT INTENDED FOR SALE TO PERSONS UNDER THE AGE OF 18’ on the label”

- Several states had policies Beckerman described as indicative of concern “with impairment and/or cannabinoid limit”:

- California officials didn’t want people to “mess around with THC isolate,” and “THC or comparable cannabinoid” was “defined as any of the following:

- Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA).

- Any tetrahydrocannabinol, including, but not limited to, Delta-8-THC, Delta-9-THC, and Delta- 10-THC, however derived.

- Hemp products may not include THC isolate as an ingredient.

- [California Department of Public Health], through regulation, may include or exclude “comparable” cannabinoids from the definition of THC, based on their intoxicating effect, or lack thereof.”

- Louisiana had “fairly new” regulations which applied to hemp items, “even if it's a cosmetic”:

- Defines “adult-use consumable hemp product” as a consumable hemp product that contains more than 0.5 mg of total THC per package, and prohibits the sale of such products to those under 21. Note this…restriction is in addition to the 18+ sales restriction applicable to all consumable hemp products.

- Consumable hemp products may not exceed a delta-9 THC concentration of 0.3% or a total THC concentration of more than 1%.

- Consumable hemp products cannot exceed 8 mg of total THC per serving.

- Minnesota “kind of just legalized edibles…with this law for CBD” which “Prohibits the sale of hemp products that contain THC or any other cannabinoid (such as CBD) to those under 21; Minnesota’s law also sets a 5mg/serving limit and 50mg/container limit for total THC in ‘edible cannabinoid products’ sold at retail.”

- North Carolina lawmakers amended their “State Controlled Substances Act to only exempt THCs in hemp in a product that does not exceed 0.3% delta-9 THC, not merely to THCs ‘found in hemp or hemp products’” as a way of matching the limits in the 2018 Farm Bill and “sort of following the [Drug Enforcement Administration] DEA’s interim final rule.”

- In Idaho, only “products with non-detectable THC are permitted” meaning, “if there's any THC, it's not legal.”

- Virginia required that products with any detectable THC to “only be sold to those 21 and older.”

- The New York Cannabis Control Board in the Office of Cannabis Management t permitted “25 milligrams (mg) total cannabinoid limit per package for food and beverage.” Dietary supplements had a “total cannabinoid limit of 100 mgs per serving and 3,000 mgs for the container again,” and the board voted to adopt changes to cannabinoid hemp regulations on September 20th to raise “in-process hemp extract” on THC, “it was three percent until yesterday, now it's five.”

- Oregon had centered regulations on hemp in “adult use cannabis item[s]” which were products that:

- “1. Contains 0.5 milligrams or more of any combination of:

- a) Tetrahydrocannabinols or tetrahydrocannabinolic acids, including delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol or delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol; or

- b) Any other cannabinoids advertised by the manufacturer or seller as having an intoxicating effect;

- 2. Contains any quantity of artificially-derived cannabinoids (see definition below); or

- 3. Has not been demonstrated to contain less than 0.5 milligrams total delta-9-THC when tested in accordance with ORS 571.330 or 571.339. This include[s] products where the testing was not sensitive enough to determine whether there is less than 0.5 milligrams of THC in the item.”

- “1. Contains 0.5 milligrams or more of any combination of:

- California officials didn’t want people to “mess around with THC isolate,” and “THC or comparable cannabinoid” was “defined as any of the following:

- Beckerman noted that when FDA analyzed hemp products, “they are going to use highly calibrated, very sensitive machinery and lab equipment” so any business or state regulator “not also using those highly calibrated, incredibly sensitive and accurate testing facilities or services, you may come up with non-detectable [sic], but it actually is detectable.” Though she considered the odds of enforcement by federal agencies “very low risk,” civil litigation was not as restricted: “you can just be sued just in regular civil court, has nothing to do with an enforcement agency at all.”

- Continuing on to artificial and synthetic cannabinoids, Beckerman said Hawaii had a prohibition that “no person shall sell, hold for sale, offer, or distribute any hemp product into which a synthetic cannabinoid has been added.” She remarked that those cannabinoids were then defined as “a cannabinoid that is produced artificially, whether from chemicals, or from recombinant biological agents, including but not limited to yeast and algae, and not derived from the genus Cannabis, including biosynthetic cannabinoids.” She was confident that Nevada officials had been the first to define synthetic cannabinoids in that way, and that officials in Hawaii and Michigan had copied it (audio - 6m).

- Nevada had been the first to set a prohibition “on the production, distribution, sale, or offering to sell a synthetic cannabinoid,” she said.

- New York had a similar standard which kept processors and retailers from making items with “synthetic cannabinoids, or D8, or D10 through isomerization.” Rules in that state for CBD “specifies an exclusion of synthetic cannabidiol,” and expressly “means the naturally occurring hemp derived phytocannabinoid cannabidiol.”

- Oregon regulators defined artificially derived cannabinoids “as a chemical substance that's created by a chemical reaction that changes the molecular structure of any chemical substance derived from the plant Cannabis family cannabaceae.” Compounds weren’t classified as artificially derived provided they were:

- A “naturally occurring chemical substance that’s separated from the plant Cannabis by any chemical, or mechanical extraction process,” making it acceptable “if you use a mechanical process or a chemical process, but it's naturally occurring.”

- “Cannabinoids that are produced by decarboxylation from a naturally occurring cannabinoid acid without the use of a chemical catalyst.”

- “Any other chemical substance identified by the commission in consultation with the Oregon Health Authority and the State Department of Ag[riculture] by rules.”

- 2022 legislation in Virginia impacted products with synthetic cannabinoids and the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Safety released a statement “doubling down and wanting people to know ‘no way’ on these chemically synthesized D8s,” regarding them as adulterants. Someone “who manufactures, sells, or offers for sale a chemically synthesized cannabinoid including, Delta 8 or Delta 10, in foods or beverage is in violation of the Virginia food and drink law.” Furthermore, “any cannabinoid that is synthetically produced via chemical reaction fails to meet the definition of industrial hemp extract” under that law.

- Highlighting packaging and labeling rules in other states, Beckerman noted that it was commonplace for products to include an “FDA disclaimer” acknowledging that statements made in advertising or on the label hadn’t been evaluated by that agency. The wording “is totally prescribed. It must be in a hairline box. It must be bold,” and she commented that the only allowance in the CFR for variance was “if you're talking about more than one statement, or more than one product, whether it's an advertisement or on the label, then you would use plural versus singular for either ‘State,’ and/or ‘statement’ or ‘product.’” Beckerman laid out several ways states had “elaborated on that statement." Multiple states required this wording on products besides dietary supplements, even though the FDA labeling requirement didn’t apply to food, beverages, or cosmetics, she said (audio - 16m).

- California required the statement to be completely capitalized, though the FDA did not.

- Hawaii didn’t require the second sentence about products “not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease” on the FDA label.

- Massachusetts utilized the slightly different wording of items not having been "analyzed or approved" by the FDA.

- Beckerman believed compliance experts scrutinized hemp product labels and would decide they “look ignorant because you're so diverting” from a “very clean and clearly written federal law, and you’re butchering it and putting it on products it doesn't belong.” Starting in Indiana, many labeling disclaimers also required a statement that the product came from hemp and “does not contain greater than 0.3% THC,” she reported, but eventually other states followed suit.

- “When Florida rolled out its [regulations] and it actually said in law you weren't even allowed to say THC on your label” and had to spell the word out, she remarked, adding “they actually enforced [it] they started pulling products off shelves almost the minute that rule became effective because the labels did not verbatim say what they needed to say.” However, she indicated regulators there had since taken that rule out “entirely.”

- Another issue was use of a QR code to retrieve additional information as allowed in California, she indicated, “but not other things that belong on a label in accordance with” the CFR. “California is by no means saying ‘you can put it there and you don't have to put it on your label,’” Beckerman said. Moreover, state leaders in the state had already adopted limits on delta-9-THC and beta myrcene under California Proposition 65, which she mentioned meant “if it's a detectable level of D9 it triggers the reproductive harm warning. If there's a detectable level of beta myrcene it triggers” a large cancer warning.

- New York labeling warned about the possibility a product could result in failing a drug screening. Beckerman told the task force it was “scary stuff, right, because we want to be able to sell our products but…we also don't want to get sued” by people not knowing a hemp item could lead to a positive drug test if they’re on “parole or probation, or they're undergoing child custody, or if their employment” would test them. Such a test “may not be able to distinguish between cannabinoid metabolites. It may read CBD as THC,” she cautioned, pointing to an August 31st statement from Michigan law enforcement announcing they’d “halted all toxicology testing processes because they're afraid they've been leading to potential inaccurate test results” as they’d found CBD could “be converted to THC in the testing process.” Beckerman stated that enforcement officials were growing “very concerned with how many cases” and people had “been affected because of prosecution because of these potentially inaccurate tests,” with one Indiana county crime lab also reportedly stopping their testing for this purpose.

- Find out more from the September 2022 research article “Comparison of State-Level Regulations for Cannabis Contaminants and Implications for Public Health.”

- Task force member Jessica Tonani, Verda Bio CEO, asked about delving into the science behind the reported false-positive tests. Beckerman answered that she wasn’t a scientist but, having worked with them as Director of Legal Affairs “when these complaints would come up,” her impression was that with “certain tests that it's simply the level of sophistication of the test itself.” They would be unable to control testing equipment or methodologies used by “these people, or agencies, or employers, or military” and “all of these different law enforcement across the nation,” she explained. Beckerman conveyed that “the devastation of the potential lawsuits when this happens” was extreme (audio - 2m).

- Nextraction Vice President of Quality Operations Eric Elgar, another task force member, followed up on the impact from changes to packaging and labeling rules in New York (audio - 1m).

- Task force appointee Amber Wise, Medicine Creek Analytics Scientific Director, inquired about the limit of quantification in “the testing for CBD and THC in blood versus products.” Specifically, she wanted to know about a “couple of states that had something about prohibiting any detectable levels of THC in the product.” Beckerman knew that some places said “no” detectable level of the cannabinoid. Wise replied that depending on the product, it could be “quite difficult to test accurately at very low levels of THC,” and distinguished between testing for a cannabinoid compound in matrix versus a metabolite in a blood sample (audio - 3m).

- Beckerman informed the group she’d been compiling a document with “examples of unusual prohibitions or requirements and…a baseline that is not unusual but that is basically replete throughout the states that have any regulatory framework is that the hemp in all of these states, it's required that they come from a [U.S. Department of Agriculture] approved source” with a “state or tribal plan, or their foreign equivalent.” She named a few exceptions in California, New York, West Virginia, “and I think, perhaps, others” based on where hemp extract was sourced from, or whether refrigeration of a product was required for safety. California rules also barred including hemp in “an alcoholic beverage or product containing nicotine or tobacco, or medical devices” (audio - 5m).

- Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) Commodity Inspection Division Assistant Director Jessica Allenton shared insight on WSDA and Washington State Department of Health (DOH) priorities with regard to hemp in food, before taking questions from the task force members.

- WSDA staff hosted a public hearing on their hemp program on September 7th. The CR-103 for the adopted rulemaking project was filed with the Washington State Office of the Code Reviser (WA CRO) on September 14th.

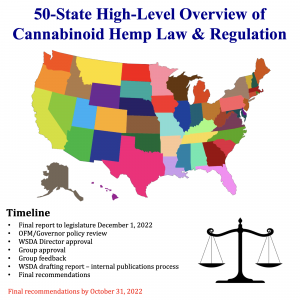

- Allenton described how the group was “two months into a four month process since we have to have the final report to the legislature on December” 1st (audio - 3m, presentation).

- Allenton confirmed the report wouldn’t “include draft bill language,” although it was “something that this group can continue to tackle. But for WSDA’s purposes our requirements are to provide a final report” rather than legislation that could be developed “outside of this process.”

- Thanking Beckerman for the information she’d collected, Allenton indicated that a staffer at WSDA had also been collecting “resource links” she planned to distribute to task force members.

- Beckerman was grateful for the clarity that the report would not prescribe legislation, but she asked to confirm members were supposed to be “looking at a proposed regulatory framework” that would rely upon a legal framework. She understood the task force would need a report “includ[ing] recommendations for regulating and allowing” hemp in food, observing that “bills can be short” while rules “can be 100 pages long, and they may need to be.” Allenton expected the task force report would “flow into” potential legislation as part of a “second step" after their input on “future things that we still may need.” She perceived their timeline for completion to be tight, and that several topics could wind up “in that ‘for-future’ bucket” (audio - 3m).

- Beckerman had another question around documents with resources that had been shared among Concentration and Safety Work Group members. Allenton promised materials would continue to be available through an online portal (audio - 2m).

- A timeline shared by Allenton specified final recommendations from the task force were due by October 31st (audio - 3m).

- An initial draft of the report would be made by staff and “it'll be a back and forth process” of feedback and approval by task force members, according to Allenton. The final report would need approval from WSDA Director Derek Sandison, she indicated.

- A review of the approved report by the Washington State Office of the Governor (WA Governor) and Office of Financial Management (WA OFM) could take “up to two weeks.” Allenton was clear that a “very quick turnaround” meant input on the report would “have to be a very quick process.”

- The goal to develop task force recommendations before October 31st would require numerous work group and task force meetings, stated Allenton. She relayed that Kelly McLain, Policy Advisor to the Director and Legislative Liaison, had told her about “things that she has already heard from this group” like “the need for using existing sanitary requirements,” appropriate food manufacturing standards, “and then lab testing by rule must include pesticides and molds.”

- Wise cast doubts on the idea the task force had reached consensus on those areas, particularly on lab standards, evoking clarification from Allenton that she was merely mentioning “really positive conversations” task force members had already engaged in (audio - 1m).

- Allenton next spoke to discussions she and McLain had with representatives from DOH, where there’d been agreement in urging “realistic timelines and what science is available.” The consensus of staff was that there may “be topics that you are all discussing where you may feel like you need a concrete answer, but it might not be available at this time,” she cautioned, as “recommendations do often include the need for ongoing research in an area.” Allenton mentioned other matters of concern to regulators, listing them as five principles for “walking before running” with hemp in food, along with rationales from officials (audio - 5m, audio - 5m):

- “1. The first step should be cannabinoids only.

- Why? We have the most information about those extracts and that makes this a good place to start from a risk perspective.

- 2. The first round of food types should be pre-packaged items only.

- Why? This reduces risk to businesses and the consumers. Inspections and regulation is then focused on food and beverage production rather than local restaurant and free dosing in coffee shops, etc. A good place to start with recommendation for continued work.”

- Pre-packaged servings of hemp in products, and “on-site dosing” like CBD in “coffee stands, you know, adding ingredients right there,” was a business practice that troubled regulators.

- Elgar voiced support for this idea.

- “3. Regulations should be in rule not statute. The regulatory agencies remain uncertain about the inclusion of numeric standards in statute.

- Why? The statute is not set in stone but difficult to change. This is an evolving area of science which makes the requirements to work within the legislative structure difficult.

- Tonani confirmed there still needed to be initial legislative approval for a hemp in food program. Allenton readily agreed regulators didn’t want to “get pigeonholed into like, numeric standards in statute,” instead preferring to have “flexibility that, as science changes, as industry changes” and there’s more information, changes could be made “in a rule setting versus a statute setting” (audio - 1m).

- 4. Expedited rulemaking authority.

- Why? The two main agency’s (WSDA and DOH) can move forward and be nimble in addressing industry needs and concerns – example is the hemp program since 2019.

- An expedited CR-105 rule process was used for adoption of rulemaking implementing HB 1210 on July 6th.

- [5]. Statute should include directions for GMP, sanitary standards, basic labeling (with rulemaking), laboratory testing requirements for pesticides, metals, mold (all with rulemaking).

- Why? We agree with providing explicit instructions to the agency’s however we need the ability to make changes as quickly as the science warrants it. The last thing we all want is to work this much and end up opening a market pathway and then having to close that market channel until the Legislature reconvenes.”

- A previous mention of a WSDA toxicologist being hired had been researched by McLain, and prospective candidates had suggested “in order to do what we were asking it was going to take, you know, 12 to 18 months.” Realistic goal setting was key to their recommendations, and not “having you all feel like you have to solve the world's hemp and food problems in five weeks.”

- Wyckoff Farms CEO Dave Wyckoff was amenable to expedited rulemaking powers for WSDA to get the program going, and asked about the department’s role in lobbying for legislation, assuming it was presented by the 2023 legislative session. He elaborated that “there are a number of people involved in the hemp industry in the state that very much would like to see us put on a more level playing field” with other states. Allenton expected that McLain, as legislative liaison, would “talk about impacts" with lawmakers, which depended on the bill language. She expected counterparts from DOH would approach lobbying around any bill the same way. “Ideally, it’s a partnership,” she said, so officials would know what was being proposed in law, and why, and whether the department’s leaders were opposed to something. Neither agency planned to advance a request bill on the topic (audio - 4m).

- Check out WSLCB request legislation under consideration for 2023.

- Beckerman wondered aloud “how are we gonna get all this done” in the allotted time, since “obviously we want to put something together as meaningful as possible.” WA Hemp in Food Task Force facilitator Steven Byers advised “staying at a high enough level” in recommendations that they weren’t dependent on highly specific research or data points, finding that level of responsibility “liberating” in the face of daunting recommendations (audio - 3m).

- “1. The first step should be cannabinoids only.

- Returning to the issue of policies and programs in other states, Beckerman proposed formatting her materials and sharing them among work group members which could be used to "form a skeleton" for their recommended system (audio - 13m).

- Allenton opened up the floor to hearing if there were particular state systems the task force or work group members wanted more detailed information on. Beckerman assured everyone she’d share what she’d learned so far, saying some state programs were “nuts,” and others were almost too “sophisticated.”

- Byers welcomed any ideas for recommendations as well as input on whether existing ideas needed more improvement before inclusion in a draft report.

- Wyckoff hoped to lift some concepts from an existing and "not overly comprehensive" program in place elsewhere, otherwise there would be a “very, very substantial burden" on WSDA officials. He further wanted their recommendations to “include both the statute and the regulations, because without the former, the latter might not be as meaningful.” Beckerman related to Wykoff’s attitude, but had seen less comprehensive methods “didn't know what they didn't know” resulting in “frankly dangerous laws…it's just such a catch 22.” She preferred “starting with…a really well drafted set and pairing it down…as opposed to starting with a poorly drafted set and just…not having the benefit of that level of concern, and sophistication that the group and the regulators would have.”

- Elgar thought "finding that perfect balance" would be difficult, and encouraged the task force to find an existing process that "deviates the least" from federal statutes, while also aiming to have hemp in food treated comparably to other processed foods. Wyckoff’s “different perspective,” was that major food and drink companies “not atypically, will have third party audits done just because those types of large customers, food and beverage customers, require it” or undertake it themselves. He also anticipated DOH staff would “go out and audit every CBD ingredient producer for food and beverage before that entity can start providing those ingredients, could take really quite some time” and would be “one of the factors that I think would be helpful for everyone to consider how we're going to…try to get [a hemp in food program] out as responsibly soon as possible.” Elgar replied that his business had “just received our hemp extract facility certification, and the state did come out and inspect this prior,” noting “that structure exists, it wasn't cheap though.”

- Task force members heard brief updates about what the Concentration and Safety Work Group had been accomplishing, and also considered product testing needs.

- According to Wise, the Concentration and Safety Work Group “met twice” and at their last meeting “we just went over relevant testing requirements for [legal cannabis] products to get a sense for what's going on currently in Washington state with that.” Additionally, she said they’d “generally agreed upon requiring some sort of batch or a lot level testing for cannabinoid concentrations, what non-scientists often call potency,” inclusive of “CBD, THC, and any other naturally occurring compounds or…any other advertised compounds.” Testing should be at “the final product level,” or the “intermediate product level when it's sold as a food ingredient,” she commented. Wise didn’t “think we agreed on as…a subgroup, of having different designations between food products and dietary supplement products, and there are two different CFRs that cover those categories of products,” meaning they’d need to make determinations on designations and standards for testing and the intermediate and end stages. Testing on “pesticides, heavy metals, microbial content, mycotoxins, and residual solvents” had been talked about, she stated, and members of the work group had been interested in “some guidance on in terms of…who's the regulatory agency or gatekeeper” of the products (audio - 4m).

- Learn more from the WSDA Testing Protocol for Identifying Delta-9 Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) Concentration in Hemp. along with Hemp Export and Import Information.

- Byers again looked for ideas to add to the list of potential recommendations, to which Wise advocated for hewing close to federal rules on dietary supplements in 21 CFR 111 and 21 CFR 117 regarding food, even though they failed to call out specific tests to perform. Beckerman argued this made trade associations like the American Herbal Products Association useful, since those groups were “good places to start in terms of manufacturing processes and certifications.” Wise talked about the differing product types and their respective testing standards, and Beckerman offered to help get links to existing testing protocols for them to consider (audio - 5m).

- According to Wise, the Concentration and Safety Work Group “met twice” and at their last meeting “we just went over relevant testing requirements for [legal cannabis] products to get a sense for what's going on currently in Washington state with that.” Additionally, she said they’d “generally agreed upon requiring some sort of batch or a lot level testing for cannabinoid concentrations, what non-scientists often call potency,” inclusive of “CBD, THC, and any other naturally occurring compounds or…any other advertised compounds.” Testing should be at “the final product level,” or the “intermediate product level when it's sold as a food ingredient,” she commented. Wise didn’t “think we agreed on as…a subgroup, of having different designations between food products and dietary supplement products, and there are two different CFRs that cover those categories of products,” meaning they’d need to make determinations on designations and standards for testing and the intermediate and end stages. Testing on “pesticides, heavy metals, microbial content, mycotoxins, and residual solvents” had been talked about, she stated, and members of the work group had been interested in “some guidance on in terms of…who's the regulatory agency or gatekeeper” of the products (audio - 4m).

- WA Hemp in Food Task Force facilitator Steven Byers prompted a discussion to schedule task force meetings in the remaining weeks before their recommendations were due to WSDA staff on October 31st (audio - 16m).

- Tonani called for additional work group meetings to make progress on topics members wished to offer recommendations upon, and Byers wanted the full task force to meet again in two weeks.

- Beckerman advocated for weekly work group meetings where members could “participate, or don't participate” in the run up to the next task force meeting.

- Wise believed it would be possible for her work group to get some recommendations put together for the full task force ahead of the next meeting. She needed input from other work group leaders, either in an open meeting or “behind the scenes.” Wise was direct in saying that the task force was “already pretty burdensome for my schedule, and I'm sure other people's as well.”

- Bonny Jo Peterson, Industrial Hemp Association of Washington (IHEMPAWA) Executive Director expressed her willingness to meet more often, as “I feel we're pretty far behind.” Elgar concurred with her assessment,

- Allenton elaborated on the difficulty WSDA staff faced managing this task force as well as the Hemp Commission Task Force, which had matching timelines for obtaining member recommendations and drafting reports for publication by December.

- Following a poll conducted after the meeting, members agreed to meet eight days later on Thursday September 29th.

Information Set

-

Announcement - v1 (Sep 12, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Agenda - v1 [ Info ]

-

Chat Log - v1 (Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Chat Log - v2 [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Complete (2h 37m 15s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Welcome - Steven Byers (4s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Introduction - Jill Wisehart (43s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Introduction - Megan Moore (50s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 04 - Agenda - Steven Byers (8m 42s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Presentation - Cannabinoid Hemp State Law and Regulation - Joy Beckerman (23m 13s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Presentation - Cannabinoid Hemp State Law and Regulation - PAL - Joy Beckerman (15m 35s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Presentation - Cannabinoid Hemp State Law and Regulation - Questions (1m 1s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Break (45s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 14 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Jessica Allenton (3m 18s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 17 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Timeline - Jessica Allenton (2m 49s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 19 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Agency Feedback - Jessica Allenton (5m 22s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 21 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Agency Feedback - Jessica Allenton (5m 15s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Questions (20s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 24 - Presentation - WSDA and DOH Priorities - Comment - Joy Beckerman (2m 30s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 27 - Next Steps - Steven Byers (40s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 28 - Question - Task Force Recommendation Process - Amber Wise (4m 35s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Comment - Jessica Tonani (5m 37s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 30 - Question - Task Force Activity After Recommendations - Amber Wise (1m 15s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 31 - Next Steps - Steven Byers (46s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 32 - Question - Work Group Reports - Amber Wise (56s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 33 - Next Steps - Scheduling Task Force Meetings - Steven Byers (15m 59s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 34 - Update - Work Group - Concentration and Safety - Amber Wise (4m 8s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 36 - Question - Deferring Some Recommendations - David Gang (4m 45s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 37 - Wrapping Up - Steven Byers (1m 26s; Sep 21, 2022) [ Info ]

-

-

WA Hemp in Food Task Force - Meeting - General Information

[ InfoSet ]

-

Announcement - v1 (May 16, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Announcement - v2 (May 18, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Document Repository - WSDA (Sep 6, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v3 (Nov 30, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v4 (Jan 12, 2023) [ Info ]

-