Advocates learned about Washington's legislative process from a Legislative Information Center staffer including specific steps to track and participate virtually in the 2021 session.

Here are some observations from the Tuesday January 5th Washington Legislative Information Center (WA LIC) class for Prevention Voices.

My top 3 takeaways:

- A “facilitator” of Prevention Voices introduced Washington State Legislative Information Center (WA LIC) staff to provide a free class on the legislative process.

- Kitsap Public Health District Community Liaison Megan Moore welcomed attendees on behalf of Prevention Voices, a group of “substance use prevention professionals who are just here to educate about youth substance use prevention" and who were not “lobbyists.” She said the presentation was for those who wanted “a little bit more training on how to participate in session” and introduced Laura Love, a WA LIC Information Specialist, to lead the training segments.

- In October 2020, Moore cautioned the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) about “better access to marijuana, and alcohol, and tobacco products” and a “decreased perception of harm for the community” (audio - 3m).

- WA LIC was established by the legislature to “provide courteous, accurate, and timely information about the Legislature and the legislative process to the citizens of Washington State and the members and staff of the Legislature.”

- The Center’s portfolio covers lawmaker communication as well as educational and legislative publications:

- The presentation the group received was one of WA LIC’s “free classes to the public and to state agencies on understanding the legislative process and navigating the legislative website.”

- The Center schedules classes on request at “360-786-7573 or email us at support@leg.wa.gov. We recommend that Navigating the Legislative Website (Class Handout, video) is taken as a precursor to the Advanced Legislative Website Use class (Class Handout). The classes can be tailored to either introductory or advanced levels of knowledge and experience, and can be custom designed if needed.”

- Kitsap Public Health District Community Liaison Megan Moore welcomed attendees on behalf of Prevention Voices, a group of “substance use prevention professionals who are just here to educate about youth substance use prevention" and who were not “lobbyists.” She said the presentation was for those who wanted “a little bit more training on how to participate in session” and introduced Laura Love, a WA LIC Information Specialist, to lead the training segments.

- WA LIC Information Specialist Laura Love gave tips for successful advocacy as she educated attendees on how lawmakers preferred to receive public input during a largely virtual legislative session.

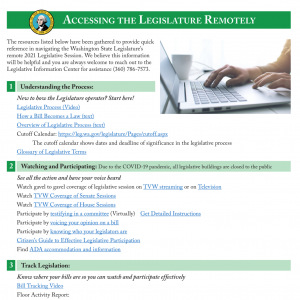

- Navigating the Virtual Session (audio - 9m, audio - 6m). Love showed attendees the legislature’s homepage where WA LIC had linked a document on Accessing the Legislature Remotely to cover “all the information you need about this upcoming virtual session.” She said that watching bills and participating in hearings was “where we will see the changes for this session.”

- Remote Sign In. Love described how to select chamber committees from the remote sign in webpage noting “if there are committee meetings, you will see” them within 24 hours of the start time.

- First select the type of committee: House, Senate, or Joint.

- Then select the committee name to see “what bills are going to be discussed in that meeting, and then you will have the opportunity to go in and sign up to testify.”

- Once a bill was selected, a person can submit written testimony, request to testify, or have their position included in the legislative record.

- Love explained that in 2021 people would have the option of submitting written comments on bills to committee members and staff before and “up to 24 hours after the start time of the hearing.”

- Love followed up after publication to note, "People will be able to sign in to testify on a bill as soon as it is scheduled, not necessarily 24 hours in advance. Could be 7 days, could be less than 24 hours. Definitely need to sign in prior to closing the testimony links 1 hour before the hearing starts."

- Committee Hearings. Love reported that all committee hearings would be hosted over Zoom and those wishing to testify during a hearing would be sent “an individual link to that Zoom meeting” which was associated with an individual’s sign up information and shouldn’t be shared with others.

- She explained what to expect after joining a meeting, as participants begin in Attendee mode until they’re called by the committee chair. Then, the person would be reconnected as a Panelist “to speak at this point.” Love said “you do not just automatically unmute when your name is called” and that it was a common problem for those testifying to still be muted.

- Video was permitted, but it was possible to join with an “audio-only” option, she noted. “A pop up box” would prompt audio-only testifiers to unmute.

- Testimony could be accepted though Zoom on a “phone only” basis where the link sent featured “the webinar ID, the password, and the phone number,” Love indicated. When calling, an individual enters the webinar ID, then the password, “and then you will join the meeting.” Phone callers would receive a notification that the person’s phone was unmuted. If that didn’t happen, “you can press *6 and that will unmute your phone.”

- Speakers were asked to identify themselves by name, Love stated, as well as any organizational relationships first. She recommended beginning with something like “thank you for having me chairperson, and here’s my opinion” on the bill that committee was hearing.

- After testimony, a person’s view would switch back to attendee mode. Love said “you can either choose to leave the meeting and continue to watch it on TVW or not watch it at all” or “you can continue to watch through the end of the Zoom meeting.” Individuals speaking on multiple bills needed to stay logged in to the meeting.

- Commenting on a Bill. Individual bill pages, for example HB 1019, offered the ability to “comment on the bill,” Love noted, but remarks sent via that route only went to the sender’s “district legislators” and not committee members nor their staff.

- Instead, Love commented that she would “highly recommend” that those testifying send written comments the “day beforehand” to allow committee staff to ensure written remarks were received by members.” She advised sending remarks to the Committee Assistant who would see that members received copies. Their contact information was located at the bottom of committee member/staff pages. Love pointed out that legislative email addresses followed a format of [first name].[last name]@leg.wa.gov, and that committee staff could also be contacted by phone. She said when written testimony was available ahead of a person’s testimony on a bill, “it gets put in the bill’s official file. So, ten years from now, you could request” the bill file through a public records process “and when you open that bill file your written testimony is a part of that official record.”

- The 2021 policy committees for cannabis legislation were the Washington State House Commerce and Gaming Committee (WA House COG) and the Washington State Senate Labor, Commerce, and Tribal Affairs Committee (WA Senate LCTA). Each included a staff webpage.

- Instead, Love commented that she would “highly recommend” that those testifying send written comments the “day beforehand” to allow committee staff to ensure written remarks were received by members.” She advised sending remarks to the Committee Assistant who would see that members received copies. Their contact information was located at the bottom of committee member/staff pages. Love pointed out that legislative email addresses followed a format of [first name].[last name]@leg.wa.gov, and that committee staff could also be contacted by phone. She said when written testimony was available ahead of a person’s testimony on a bill, “it gets put in the bill’s official file. So, ten years from now, you could request” the bill file through a public records process “and when you open that bill file your written testimony is a part of that official record.”

- Attendees had a few questions throughout the presentation.

- Donna Kelly, Community Prevention and Wellness Initiative Coalition Coordinator, (audio - 1m). Kelly asked about the best introduction when testifying. Love offered a couple of possible options and advised against an opening of “yo, legislators.”

- Kelly is listed as a Pend Oreille County Counseling Services contact on the Athena Forum.

- One participant asked, “how soon can you sign up for hearings.” Love said to expect to be able to sign in one’s position (pro, con, or other) and/or register to testify “24 hours before the committee hearing starts.” Sign ins would be closed one hour before a hearing starts. She remarked that it was possible one would not be called depending on how many wished to participate (audio - 1m).

- Moore asked about TVW coverage of the House and Senate Sessions, wondering “if they will be in speaker or gallery view,” and whether viewers would “see all of them at one time on the screen” or “only see the person speaking?” Love wasn’t sure, but “streamlining” of the process continued. She expected TVW would “go with whatever the Chair decides, or whatever the House and Senate tells them” (audio - 1m).

- An attendee asked for a way to see “all the committee hearings.” Love replied that the legislative homepage would always list committee hearings happening that day with links and agendas. The Agendas, Schedules, and Calendars search page “put you in your current week” initially while also allowing for custom searches of date ranges, specific bills, and more, she reported. Love observed that individuals could register for email notifications from the legislature and set preferences to track bills, committees, or floor calendars. She said every Wednesday the committee meeting schedules for the following week were sent out and people could sign up to receive a “combined meeting schedule” as well as updates from WA LIC. “This is a great way to sign up to have the information come to you rather than have to go in and look through the agendas and calendars every week,” Love told the group (audio - 5m).

- Donna Kelly, Community Prevention and Wellness Initiative Coalition Coordinator, (audio - 1m). Kelly asked about the best introduction when testifying. Love offered a couple of possible options and advised against an opening of “yo, legislators.”

- Love went through the process of forming legislation into law in Washington state, including details on amending bills and scheduling floor activity (audio - 33m).

- WA LIC provided educational resources dedicated to the legislative process in video and text formats as well as a webpage on how a bill becomes a law.

- Love began an “abridged” version of her usually hour-long presentation by explaining “the legislative branch writes the laws, the executive branch enforces the laws, and the judicial branch interprets the laws.” She noted that the legislative branch was the “author” of the state’s constitution, the “guidelines” for the state government.

- Washington’s legislative branch operated on a biennial calendar with a 105-day long session in odd numbered years, and a shorter 60-day session in even numbered years, Love said. She then indicated that bills from the long session could be “carried over into the next session within the biennium.”

- Love noted legislative sessions began on the “second Monday in January.” In long sessions, lawmakers “write the biennium budget” and followed up with “a supplemental budget” during short sessions.

- Budget bills were prefiled in both chambers. In the House, HB 1093 was a second supplemental operating budget bill for the 2019-2021 biennium while HB 1094 was for “Making 2021-2023 fiscal biennium operating appropriations.” The senate companion bills were SB 5091 and SB 5092, respectively.

- Special legislative sessions could be convened by the Governor, or by a super-majority of both chambers, and last up to 30 days, she added.

- Washington has 49 state legislative districts, which Love explained were equal in population and based upon the U.S. Census Bureau’s information for the state. She said the federal government had until April to get 2020 census data returned to the State so the Washington State Redistricting Commission could “redraw those districts so that they are even in population” independent of the legislature. The citizens of each district received two representatives and one senator to represent them, Love stated.

- At a Washington State Legislative Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis meeting in December 2020, Senator Curtis King wondered aloud whether census updates could impact the State’s allotment of cannabis retail licenses for social equity applicants.

- On January 5th, WSLCB leadership indicated the agency had shared "cannabis industry space" data with census officials.

- Citizens were able to propose laws to the Legislature or the entire electorate through Washington’s ballot initiative process, she commented, as well as referendums on adopted or proposed legislation.

- Initiative 692 in 1998 and Initiative 502 in 2012 were proposed and adopted by voters via the ballot, establishing the state’s first medical cannabis law and first recreational legalization law, respectively.

- Love indicated that bills introduced by lawmakers could come from “anywhere,” but had to be submitted to the Washington State Office of the Code Reviser (WA OCR) whose staff drafted the bill. A legislative sponsor returned the draft bill to WA OCR with their signature which “turned it from a draft bill to a real bill.” A bill number and tracking webpages were created, she elaborated, with House bills (HB) numbered beginning at 1000 and Senate bills (SB) beginning at 5000.

- Love commented that some legislation had the “exact same bill, verbatim, no changes” introduced in both chambers; these bills were called “companion” legislation. She acknowledged the many ways and opportunities bills had to be substituted or amended before being voted upon by a legislative chamber, and believed companion bills could increase the odds of passage. Love said if companion bills were both advanced, legislative leadership made a choice on which chamber’s version should be voted on.

- The first reading was the “introduction of a bill,” she said, where it was assigned to a committee for further consideration. Committee hearings provided insight on a topic and “constituency feedback” on bills before they were considered by all the lawmakers in a chamber, Love told the group. Most bill hearings would include remarks “from the prime sponsor of a bill,” she said, and committees sometimes convened for work sessions to learn about subject matter independent of particular legislation. Committees held executive sessions to “take action on a bill” by altering it, making a recommendation for or against passage, offering a substitute bill for consideration by the whole chamber, or sending a bill to another committee, Love observed. She described how “almost all bills start off through a policy committee” like WA House COG or WA Senate LCTA before going through a fiscal committee. She noted, “if the bill is not going to have a $50,000 impact on the budget then it does not need” to be heard by a fiscal committee in order to proceed.

- Love highlighted how the Rules committees in each chamber functioned differently from other committees and were able to decide “which bills are going to be eligible to move forward in the process.” Bills are added to a green sheet in the Senate, and a consideration calendar in the House which she described as “generally bills that are assumed to have less opposition.” By contrast, Love said that “x-file” legislation was “known to have more opposition” so what sheet a bill was listed on contributed to the odds the bill would be advanced.

- From WA LIC’s Guide to Lawmaking: At each Rules Committee meeting, members are allowed to move or “pull” a predetermined number of bills from the Senate white sheet to the green sheet or from the House review calendar to the consideration calendar. These moves are called pulls. Bills are generally pulled from one sheet to another without debate and the bills are then eligible to go to the floor at the next meeting.

- During this unprecedented session, the Washington State House Rules Committee (WA House RUL) and the Washington State Senate Rules Committee (WA Senate RULE) will have their meetings broadcast for the first time.

- Bills selected by a chamber’s rules committee get scheduled for a second reading, which Love described as when lawmakers “discuss the meat and merits” of a particular bill. This was also the stage at which committee substitutes to a bill were considered, she added, and if adopted the advancing legislation was titled a “substitute” House or Senate bill before being amended further.

- “Page amendments” tended to be small and targeted to a minor text change, Love explained, while “striker” amendments remove “everything after the enacting clause and inserts new language.” She stressed that Washington law didn’t allow lawmakers to change the enacting clause of a bill, but could alter everything else about it. Objections under this provision were referred to as "Scope and Object" challenges, Love added.

- Bills amended on a chamber floor were considered “engrossed,” Love stated, and were sent back to a rules committee unless lawmakers chose to suspend that requirement and move legislation to the third and final reading, which she indicated happened regularly. If a bill passed the third reading vote it would be sent to the opposite chamber for a matching process of consideration, proposed amending, and passage, she elaborated. Should the bill be changed, Love added, those changes would need to be approved by the chamber of origin either in their entirety or through a conference committee to negotiate a compromise between the various versions of a bill. She indicated that either chamber could refuse this option but that should they agree on a compromise, a conference report was created with the new draft of the bill which was voted on by both chambers.

- See Cannabis Observer’s coverage of the 2020 supplemental budget conference committee report adoption.

- Legislation passed by both chambers would be delivered to the Governor’s Office, where the Governor could choose to sign, partially veto, or completely veto the bill, she said. Love told the group that “only in budget” bills could the Governor execute “line item vetoes.” The Governor had five days from receiving a bill to take action on it, not counting Sundays. If, however, bills arrived at the Governor’s Office in the last five days of session, the Governor was allowed 20 days to sign or veto them, she added.

- A signed bill became law following formal registry with the Washington State Secretary of State (WA SOS) and “starts on its effective date.” While bills could specify their own effective date, Love told attendees most took effect 90 days “after the last day of session.”

- Love explained the session cutoff calendar was a series of deadlines when bills must complete certain benchmarks before the end of a legislative session known as Sine Die. She noted some bills could be designated “necessary to implement the budget” (NTIB) and receive extra time for lawmakers to act.

- The Guide to Lawmaking describes Sine Die as “a longstanding tradition in the legislature that either occurs when both chambers are completely finished with legislative business or at midnight on the last day of session, whichever happens first.”

- Love concluded her presentation by pointing out the most important resource she could share was WA LIC’s support services contact information.

Information Set

-

Announcement [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - Prevention Voices

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 00 - Complete (1h 10s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 01 - Class Introduction - Laura Love (47s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 02 - Navigating the Virtual Session - Laura Love (9m 27s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 04 - Navigating the Virtual Session - Question - Committee Sign In (1m 10s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 05 - Navigating the Virtual Session - Laura Love - continued (5m 31s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 06 - Navigating the Virtual Session - Question - TVW Coverage - Megan Moore (1m 29s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 07 - Navigating the Virtual Session - Question - Committee Meeting List (4m 59s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 08 - General Legislative Process - Laura Love (33m 6s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Prevention Voices - 09 - Wrapping Up - Megan Moore (2m 22s; Jan 11, 2021) [ Info ]

-

-

WA LIC - Class - General Information

[ InfoSet ]