A keynote speaker went over trends in cannabis consumption related to high potency products, aiming to dispel the argument that product prohibitions undermine public health goals.

Here are some observations from the Friday September 16th University of Washington Addictions, Drugs, and Alcohol Institute (UW ADAI) 2022 Symposium on “High-THC Cannabis in Legal Regulated Markets.”

My top 3 takeaways:

- The first keynote speech of the symposium on “Market Trends in High Potency Cannabis Products” was presented by Jonathan Caulkins, a guest researcher with a history of evaluating the Washington cannabis market who expressed skepticism about permitting regulated concentrates.

- Beatriz Carlini, UW ADAI Research Scientist in charge of the ADAI Cannabis Education and Research Program (CERP) and the symposium Program Chair, warmly greeted Caulkins. Admitting she’d been "his fan since 2014," she believed “many people here already have heard and read the wonderful things” he’d published. She identified his position as a Professor of Operations Research and Public Policy at the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU, audio - 1m, video).

- In 2009, Caulkins challenged the notion that U.S. cannabis legalization could significantly impact the level of violence that had been present in the Mexican drug war. In 2015, he argued that data indicated cannabis consumers were unlikely to be college graduates.

- Cannabis articles published by Caulkins’ or with his contribution include:

- Altered State? Assessing How Marijuana Legalization in California Could Influence Marijuana Consumption and Public Budgets (2010)

- Developing Public Health Regulations for Marijuana: Lessons From Alcohol and Tobacco (2013)

- Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know (2016, 2nd Edition)

- Evolution of the United States Marijuana Market in the Decade of Liberalization Before Full Legalization (2016)

- The Real Dangers of Marijuana (2016)

- Radical Technological Breakthroughs in Drugs and Drug Markets: The Cases of Cannabis and Fentanyl (2021)

- Caulkins had also worked as a researcher for the RAND Corporation Drug Policy Research Center on studies of the Washington State cannabis sector.

- Before the Grand Opening - Measuring Washington State’s Marijuana Market in the Last Year Before Legalized Commercial Sales (2013)

- After the Grand Opening - Assessing Cannabis Supply and Demand in Washington State (2019)

- Cannabis Legalization and Social Equity - Some Opportunities, Puzzles, and Trade-Offs (2021)

- Caulkins, though “thrilled and honored” to speak, cautioned the audience that "I think my job is to make you uncomfortable." He planned to “try to present data and ideas that will challenge things that you think you know about this topic.” He promised he would “talk from the policy and societal level” about the topic, letting others “do a fantastic job of explaining the laboratory science” (audio - 2m, video).

- First, he would argue “legalization of supply by for-profit companies as opposed to legalization of use is a major driver of the spread of high potency cannabis products.”

- Additionally, Caulkins commented that he thought “legalization of commercial supply is a major driver of other important themes that are also threats to public health and they are all wrapped together and at times are hard to sort out.”

- Finally, accepting cannabis legalization “as a given,” Caulkins wanted to “think that the high potency products specifically are a threat and ask ‘what can one do about that from a policy perspective,’ and particularly entertain the idea of what would happen if some specific cannabis products were banned.” He wondered if such a plan would “generate an illegal market that would eliminate the benefits of the ban and create the problems of illegal markets because illegal markets are what fascinates me.”

- Beatriz Carlini, UW ADAI Research Scientist in charge of the ADAI Cannabis Education and Research Program (CERP) and the symposium Program Chair, warmly greeted Caulkins. Admitting she’d been "his fan since 2014," she believed “many people here already have heard and read the wonderful things” he’d published. She identified his position as a Professor of Operations Research and Public Policy at the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU, audio - 1m, video).

- Caulkins presented arguments and data on cannabis concentrates, for-profit markets, wholesale prices, types of cannabis use, and the implications of national legalization and product prohibitions.

- For-Profit Legalization (audio - 8m, video)

- Caulkins made clear that adults choosing to use “a high potency cannabis product, that's a tremendously important choice for them that can be directly informed by this fascinating scientific literature, but that's not something that policy makers or public health people get to decide.” But “as a society…are we going to legalize a commercial, or for-profit supply,” he asked, “with many ramifications including the proliferation of these high potency products.”

- Attempting to “help you walk in the shoes of the companies," Caulkins laid out his reasoning for why commercial sales would have predictable impacts. First, he believed cannabis legalization “fundamentally changes the whole structure, performance, and conduct of the cannabis producing sector.” He felt a “big myth with legalization” was that the regulated market would “be same old, same old, just without arrests.” Caulkins was confident that two decades earlier “the typical cannabis producer inside the United States was growing 99 plants because there was a federal law that kicked in at a hundred plants.” Growing indoors with artificial lighting helped producers avoid arrest, but he called it “totally crazy. No other plant-based product you buy at the grocery store is grown that way,” he stated.

- Cannabis was among crops which had utilized practices from urban horticulture and vertical farming, which had received federal research funding related to other commodities. With indoor farming expected to be a growing sector between 2022 and 2028, the practice of indoor cultivation had been reported by the media to be the ‘future of farming.’

- Looking to Canada, Caulkins admired the scale with which cannabis could be grown and “what it means to be efficient in the legal production of a plant” where their “typical grow facility there can be a million square feet.” He derided other cannabis producers, describing Canadian “grow masters” that weren’t “people who commune with the plant and talk to it and sweet tones to try to get it to flourish. They're often PhD agronomists bringing modern agricultural science to bear.” Professionals there were “able to produce much higher potencies through better growing technologies and better strains,” Caulkins said.

- Furthermore, with legal production and processing, there were now industrial machines for extracting "a lot of the cannabinoids," he noted. While the “flower buds have the highest concentration,” Caulkins asserted that there were “lower concentrations of cannabinoids there in a bigger part of the plant” which “adds up.” In the prohibited market, he assumed this biomass was “unrecoverable” and “thrown out.” Caulkins claimed that when commercial cannabis operations recognized they “can capture those,” this created a business motivation “to change our consumption patterns from mostly flower to, ballpark, of 50/50 mix of flower and extract-based [tetrahydrocannabinol] THC, and industry succeeded.”

- Next, Caulkins mentioned data from Canada and Colorado suggesting sales of cannabis flower diminished in relation to concentrates in the years following legalization. He called it another “reason why legalization induces this change” towards products with greater cannabis concentrations, as legal access could offer “hundreds of different products” as contrasted with a caricature of a 1990s “retail drug dealer" who couldn’t stock many items “in their trench coat pocket.”

- Another theme Caulkins emphasized was that businesses in legal cannabis sectors faced a “strategic challenge” as they were “resisting the downward price pressure that comes from…basic cannabis becoming a commodity.” He added that a way to “fight commoditization and downward pressure on prices” was through product variety, though he was dismissive of attempts by companies to claim their cannabis was organic or earned an appellation.

- These drivers of products with higher cannabinoid concentrations were intertwined with legalization policymaking, said Caulkins, who recognized that the expansion of cannabis concentrates wasn’t only limited to places with legal cannabis. He showed cannabis seizure data from the Mexican border, with a graph of cannabinoid concentrations in “marijuana” and “sensimilla” increasing prior to legalization in Washington and other states, but argued the trendline contained “a step jump up with legalization.” Caulkins wasn’t an advocate of claims that “the trend towards higher potency over the last generation is induced by legalization, but I am claiming that legalizing for-profit supply is a driver” of products’ expanding availability and use.

- Wholesale Prices (audio - 5m, video)

- Caulkins placed “high potency” products in the “top 10 list of the biggest public health threats of legalizing commercial supply,” while qualifying that he doubted it was “perhaps, even in the top five.” He was also concerned about the declining price of retail cannabis, which “has been really dramatic,” estimating it worked out to “essentially an 80% decline in the price per gram before adjusting for the change in potency.” Caulkins offered California as a proxy for national cannabis wholesale prices before legalization of cannabis “because that was the biggest market.” His presentation showed that:

- California wholesale prices were “down 82%” between 2010 and September 2022, from a reported $5,500 per pound, to $1,000 according to the U.S. Cannabis Spot Index.

- National and British Columbia cannabis prices were offered as an approximation for Washington wholesale rates, declining “about 77%” from $4,085 per pound to “~$950” over the same period.

- Washington retail prices were estimated to have dropped by “about 75%” between 2006 and September 2022, going from $40 a gram to $10.

- Caulkins included that cannabis “pre-legalization was say 14% THC product. Now, call it 21%” He calculated at a “50% increase in potency” coupled with an “80% decline in the price per gram without adjusting for potency translates to like a 90% decline in the price per milligram of THC. That's a big change.”

- Fully expecting there “will continue to be downward pressure on prices if we go to national legalization,” Caulkins said there was “the possibility that the production cost after national legalization could be down in the range of $10 a pound.” His “thumbnail explanation” was the potential to “get a thousand pounds per acre from cannabis. It's a very productive plant.” Speculating that agricultural extension data might show the value of an acre of tomato crops as $10,000, which he called “maybe vaguely similarly difficult to grow,” with cannabis that could amount to “two cents a gram. That's a penny or two per joint” before packaging and distribution.

- Under the assumption that his comparison of tomatoes to cannabis was credible, Caulkins went on to offer the perspective that ketchup or sugar packets of about a gram amounted to “about three cents each.” He argued that cannabis flower could reach similarly low values that “we give away in other contexts.” This scenario amounted to a “radical challenge" in the cannabis market and to public health, he commented, and cannabis companies would have “to figure out how to get you to pay" for items. Caulkins drew parallels to the bottled water industry, where companies convince “us to pay two or three dollars a bottle for something that's almost indistinguishable from a product that's basically free.” With national legalization and presumed “large-scale modern agricultural production,” he anticipated cannabis businesses would “have to figure out how to get you to pay what you're willing to pay…for something they can produce for a very low price.”

- As one of the few legal states without the right to cultivate cannabis in a personal residence, at publication time Washington consumers were more reliant on products and prices set by cannabis licensees, lawmakers, and the unusual conditions of a state legal market operating under a federal prohibition.

- Caulkins placed “high potency” products in the “top 10 list of the biggest public health threats of legalizing commercial supply,” while qualifying that he doubted it was “perhaps, even in the top five.” He was also concerned about the declining price of retail cannabis, which “has been really dramatic,” estimating it worked out to “essentially an 80% decline in the price per gram before adjusting for the change in potency.” Caulkins offered California as a proxy for national cannabis wholesale prices before legalization of cannabis “because that was the biggest market.” His presentation showed that:

- National Legalization (audio - 5m, video)

- Among numerous consequences of national legalization, Caulkins turned to marketing after it “happens and we go from little $50 million a year cannabis companies to national and multinational brands the way that we have in other consumer products” where it was normal to see “marketing increasing sales to a product segment.” What he found to be less considered was his fear that large corporations could “act strategically to reposition a product in the social space.”

- Again drawing parallels to other products, Caulkins talked about the history of tobacco product marketing and “pioneer[ing] a new market with women” in the U.S. He also noted wine interests deliberately repositioned their product towards “something that's associated with fun and friends, and maybe especially women because men already have beer for that space,” concluding that by “2022 what space in our society does that product occupy? Wine is no longer confined to be something we think of with meals.” Caulkins found this strategy had also been applied to hard alcohol, whose interests worked to reform laws and be included at “baseball games and football games” by changing packaging and labeling to look more like beer “and then that led to the hard ciders and seltzer world.”

- See a 2020 opinion piece covering consumer trends in wine, “A Short History of Wine Marketing, Particularly in California.”

- Caulkins hoped public health advocates would lobby federal officials who were “contemplating, nationally, legalization of for-profit supply. This is sort of the message that we would deliver…among the myriad things that you are thinking about in this political process…try to also remember that one of the consequences will be greater availability and use of high potency cannabis products.”

- Frequency of Use (audio - 6m, video)

- Following legalization by states, Caulkins relayed “changes in consumption patterns that are concerning for public health” weren’t limited to “just the high potency products.” He talked about "frequency of use and intensity of use,” showing “household survey data” regarding “how many Americans self-report use of a cannabis product in the last 12 months” beginning in 1992. That year represented “the end of the 12 years of Reagan-Bush tough cannabis policies. That was the low point in modern cannabis use,” he remarked, and “since then, the number of people who report use in the last year has almost tripled.” Caulkins attributed this both to population growth, as well as “a doubling in per capita use,” and believed most Americans would accept such an increase “in order to purchase getting rid of all of the costs and ugliness of drug prohibition in illegal markets.”

- However, looking at the self-reported statistics of individuals who had consumed cannabis in the past month, he said there had been a “quadrupling" since legalization while “the number of days of use has increased sevenfold since that nadir in 1992.” Speaking for public health officials, Caulkins said their concern was “in daily and near daily users,” which had gone from “under a million” in 1992 to “over 12 million Americans.” Attributing this to a “repositioning of the product in its function in our society,” he explained that “a generation ago, cannabis was like alcohol…predominantly a recreational drug” which “people did for fun at parties on weekends.” Recognizing that “about one in 10 people were using [cannabis] much more frequently, many of them had some sort of substance use issues. But the great bulk of people were not using it daily or near daily.” More recently, Caulkins claimed “fully 40% of current users report using daily or near daily much more like the pattern for cigarettes” and that this cohort of consumers accounted for “for 80% of the sales” of cannabis. Because of this, he viewed occasional cannabis consumers as unimportant to industry interests.

- Heavy use by a minority of consumers had also been identified in alcohol research, though some research has posited that “nine in 10 adults who drink too much alcohol are not alcoholics or alcohol dependent.” 2021 Gallup survey results indicated overall alcohol consumption by adults had been fluctuating since states began legalizing cannabis.

- Intensity of Use (audio - 5m, video)

- The dosages available “in terms of THC per day” had become “more intense” as well, Caulkins asserted. Going from “the typical user in 2000 to the typical use session in 2022,” he estimated that in 2000 the average consumer of a twice-weekly, 0.4 gram joint with 4% THC ingested “less than five milligrams per day of THC on average.” For 2022, he outlined average consumption “at 1.6 grams a day on average, of 20% THC. It's 320 milligrams per day on average, that is a 70-fold increase in average THC consumption,” he commented.

- Behavioral health impacts from such an increase were an open question for Caulkins.

- “Maybe not, the human body is really pretty amazing. There is this phenomenon of tolerance, we can get used to things and maybe the people who are using 70 times as much function just as well in society, they’ve just adapted to this.”

- “But sometimes the dose makes the poison. So, by a weird coincidence the same numbers apply to cocaine…down in South America indigenous communities have been using the coca leaf to make coca tea… and the amount of cocaine molecules that you consume when you have a cup of coca tea is less than five milligrams.” Prior RAND research “estimated total cocaine consumption” in the U.S. “as well as estimating the number of frequent users” showing “327 metric tons divided by three million chronic users: 290 milligrams per day, about a 70-fold difference. And now ask, is there any important behavioral or health difference between having a cup of coca tea per day or consuming cocaine at the intensity of chronic cocaine users in the United States and I think there might have been.”

- Turning to consumption of caffeine, Caulkins spoke of “my favorite drug, which is Diet Coke” but decided coffee might be a more relatable caffeination commodity for the Seattle-based event. At 76 milligrams a day (”my normal daily dose”), he calculated that a seventy fold increase was equivalent to “35 grande Starbucks cappuccinos every single day.” Caulkins joked that this level of caffeine consumption didn’t phase the audience, “but in the rest of the country people think that's a big increase” and that other regions of the country “would say there might be” health consequences. He went so far as to mimic a stutter, a possible reference to signs and symptoms of caffeinism which, like cannabis, has been correlated with increased risk of psychosis.

- The early 20th century precursor to Caulkins’ favored drug, Coca-Cola, mixed caffeine with cocaine. Some estimate that each glass contained around nine milligrams of the substance.

- For Caulkins, “the grand experiment that we as a society have embarked upon is finding out whether or not this substance which was basically harmless at five milligrams per day remains harmless at 300 milligrams per day and the jury is still out.”

- In the 1980s, the level of cannabis use Caulkins termed “harmless” triggered calls for execution from some in law enforcement. Cannabis consumption "on a few occasions" was enough to keep Douglas H. Ginsburg from being confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1987. A study of arrests between 1990-2002 found “82% of the increase in drug arrests nationally (450,000) was for marijuana offenses, and virtually all of that increase was in possession offenses…Of the nearly 700,000 arrests in 2002, 88% were for possession,” regardless of the frequency or intensity of use.

- Prohibitions (audio - 15m, video).

- Presuming that products with high concentrations of THC were a particular concern, Caulkins believed “there's a set of policy implications that are terrifically important but are dull,” although he recognized the importance of, and supported, regulations around packaging and labeling, education, prevention, data collection, and monitoring. But he was likely to “want good labeling even if I wasn't singularly concerned about high potency products.”

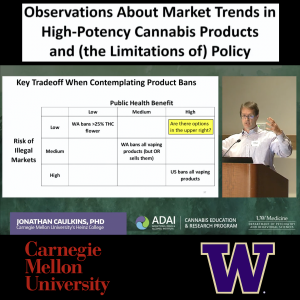

- Caulkins raised a “more difficult question, which is this issue of product bans,” particularly on “cannabis products like banning waxes and dabs, or banning vaping” or cannabis flower “that is above a particular potency cut off.” A flower THC limit of 15% had been added in the notoriously cannabis-tolerant Netherlands, he stated.

- A 2018 review from the Transform Drug Policy Foundation claimed the 2011 policy limiting cannabis to 15% THC may not have been uniformly implemented, and asserted “the potency threshold is arbitrary” with “no evidence it would reduce health harms.”

- Caulkins felt that “very high taxes [are] sort of similar to the way you think about a ban. If the tax difference is modest, then it is not a major concern. But if the tax difference is big then it almost begins to operate like a ban.” He considered whether or not product specific bans would incentivize an illicit market that undercut the public health benefits of the product ban. The potential for an illicit source of product was enough for “some people [to] say that vetoes the whole idea,” but his perspective was that illicit operations would have to be “selling that product at a price point that induces consumers to choose that illegal product over the legal alternatives.”

- Involving the confluence of several factors, Caulkins identified the enforcement of product bans as key, since “illegal production is going to happen because producing in an unlicensed and unregulated way will always be less expensive than producing while following the rules…If the legal folks have to follow all the other rules and the cheaters don't, the cheaters will have an advantage and they will be able to thrive.” He offered the example of a “gray market” medical grower whom he encountered “complaining about all the regulations,” leading him to doubt the person knew “what honest business people have to put up with.”

- “The point is it's a case-by-case thing that depends on what thing you're talking about banning and all of the economics around it,” continued Caulkins, before giving “three hypothetical scenarios to lead to the general point.”

- “Imagine that the country banned all vaping products. That would produce some public health benefit, but I do think that would also create an illegal market. There would be production in Mexico and Canada, movement across the border by organized criminal activity…It's an open question whether or not that size illegal market would more than offset the public health benefits…but I do think there would be an illegal market there.”

- “Now suppose Washington State alone banned vaping products, but Oregon said ‘we're open for business. We're going to sell these.’ I believe that some of those vape pens would make it across the state border. But, I don't think that would predominantly be done by criminals carrying semi-automatic weapons. I would suggest thinking about that the same way that fireworks crossed state borders 25 years ago…it would undercut some of the public health benefits, but it wouldn't be a particularly destructive illegal market.”

- Find out more about Washington State firework regulations.

- Finally, “suppose Washington State tried to ban flower that was more than 25%. My guess is that would not create much of an illegal market. I think most people who want a high potency flower would say ‘24% and the convenience of buying at a legal store is good enough for me.’”

- Caulkins suggested taking “those three cases and now lay them out on the basic analytic framework that should inform decisions of ban or not ban a product.” With a goal of maximizing the public health benefit and minimizing the risk of the illegal market, he plotted the three scenarios and observed that “the bigger reach on the public health side, the bigger the risk of an illegal market.” However, Caulkins wouldn’t “stand for” an objection that “just says ‘ban of products always fail,’ that is just false. It's observably false.” His examples of this were:

- “A prohibition in this country against walk-behind rotary lawn mowers that do not have a dead man’s switch. That was put in place in 1982.” With the added cost, “there is room for a potentially illegal market on people selling walk-behind rotary lawn mowers that do not have a dead man's switch. My city is not plagued by organized crime, drive by shootings, driven by that illegal market. That is a product ban that works at achieving some public health safety benefit without inducing any illegal market”

- “In Europe, you can buy chocolate candy eggs that have little toys in them…Those are banned in the United States…When my kids were young our neighbor across the street” brought them “Kinder Surprise candies and my kids were delighted. So there was illegal activity at some level but it was like that cross-state borders for fireworks.”

- “I've spent the last year looking at the history of prohibitions of fireworks and the related illegal markets. I think it's a highly relevant example for us today, because there's a direct analog to potency. The short summary is that the United States went through first free markets, then prohibition, then legalization of personal fireworks very much the way that we did with cannabis just a little bit earlier. And ironically, there are other parallels like the number of emergency room mentions per hour of use is spookily similar for fireworks and for cannabis. But to oversimplify there was this 1966 child protection act” which “took a market that had previously had highly potent fireworks available for general use, up to 3,000 milligrams of black powder, and put a potency cap of 50 milligrams.” The result was “a lot of informal cross state line trade in federally illegal consumer firework products that generated no big crime issue, undercut some of the benefits. There is also an illegal cross international border trade with products over 50 milligrams produced in Mexico and brought into the United States by criminal organizations. It is not a multi-billion dollar market, but there is a little bit of that.” The number “of injuries, especially the number of eye injuries,” had risen and fallen based on liberalization of state policies, he argued.

- Policy on absinthe had been a "spectacularly successful prohibition for nearly 100 years" because people interested in that alcohol “had the opportunity to consume many close substitutes of other kinds of hard liquor” even as concerns around the product were “mostly unfounded." Nonetheless,“it's a demonstration that a product ban does not always produce any illegal market.”

- Bans on caffeinated alcohol products were largely ineffective, as “it is defeated by do-it-yourself at home, rum and coke, but it has not generated an illegal market.”

- A ban on flavored cigarettes “has reduced youth smoking” without “a large illegal market in flavored cigarettes.”

- Lawn darts “were banned in 1988. I do not know of any organized crime groups that are trafficking in lawn darts. I do note that YouTube does have do-it-yourself instructions for how you can fabricate [lawn darts] your own home.”

- Caulkins concluded that “when thinking about product bans, you're basically balancing public health benefits against the risk of illegal markets.” He believed it to be “absolutely not responsible to say all product bans fail” or always “create illegal markets that undercut all the public health benefits, and create big problems.” Even without certainty “what bans will work best,” Caulkins advocated for regulators to “use this tool.” He urged officials to “start low, go slow, find those products which are particularly egregious and which have a relatively small customer base as your starting point.” To him, it was “a small public health benefit, but I think there's low risk” and provided “experience with what does, or does not work in terms of product regulations and bans.”

- For-Profit Legalization (audio - 8m, video)

- Following his remarks, Caulkins took questions about prohibiting vapor products, cannabis as a substitute for other substances, local bans, and product marketing.

- “What would happen if Washington implemented a ban on vaping products, [and] Oregon did not initially, but then it followed later?” (audio - 2m, video)

- Caulkins understood the potential for an illegal market, however his expectation was “you'd have that informal cross-state sort of fireworks style thing..if Washington leads. How do other states react?” He hypothesized that “the rest of the states might say, ‘inspired by Washington's wisdom. We will come along also,’ and then eventually you get to a nationwide ban where you would expect there to be substantially less use of vaping pens because, although there could be an illegal market in them, you'd expect, you know, prices to be higher, or lower availability. There's a lot of people who are just honest and wouldn’t participate in it.”

- The alternative was that “Oregon would say ‘Suckas, we’ll take your tax revenue,’” Caulkins indicated, saying that possibility seemed lower for Washington than in New England, where leaders in smaller states “would say ‘the benefits for us have collecting tax revenues on sales to all of the other big states around us would make the temptation too great.’ The West is a little different because states are bigger and you have fewer instances of major population centers on the other side of the border.”

- “Is the biggest expansion in daily, near daily cannabis use coming at the expense of alcohol. So they are substitutes?” (audio - 3m, video)

- Designating this “the billion dollar question both from industry perspective and public health perspective,” Caulkins stated that “I think 25 years down the road” as their “children and grandchildren judge us for what we did on cannabis policy now,” this topic would be one of the top outcomes judged as he felt future generations wouldn’t “care only about the cannabis-specific outcomes.” He viewed the academic literature as “more or less divided straight down the middle” and that anyone focused on the question could “cherry pick only from one side or the other.” Caulkins didn’t trust researchers to have a full grasp of the impact of cannabis legalization, since although Washington State had legalized “the other Washington has not, and that matters.” He wanted to “study it like crazy now, but no matter what we find based on data to date, I think we should remember the future is very hard to predict.”

- In 2018, Carlini authored “Role of Medicinal Cannabis as Substitute for Opioids in Control of Chronic Pain: Separating Popular Myth from Science and Medicine” for UW ADAI which called for further research on the relationship between medical cannabis and opioid cessation.

- For tobacco, “the story’s mostly bad news” as Caulkins alleged research was “less divided in its bad news. Increasing cannabis supply tends to increase tobacco smoking for instance. There's studies that suggest that tobacco smokers who are also smoking cannabis have more difficulty quitting tobacco smoking while they continue cannabis smoking.”

- Designating this “the billion dollar question both from industry perspective and public health perspective,” Caulkins stated that “I think 25 years down the road” as their “children and grandchildren judge us for what we did on cannabis policy now,” this topic would be one of the top outcomes judged as he felt future generations wouldn’t “care only about the cannabis-specific outcomes.” He viewed the academic literature as “more or less divided straight down the middle” and that anyone focused on the question could “cherry pick only from one side or the other.” Caulkins didn’t trust researchers to have a full grasp of the impact of cannabis legalization, since although Washington State had legalized “the other Washington has not, and that matters.” He wanted to “study it like crazy now, but no matter what we find based on data to date, I think we should remember the future is very hard to predict.”

- “Is there data on the size of illegal markets for flavored vape products in municipalities that have” banned them? (audio - 1m, video)

- Reasoning that “when a municipality implements a product ban, that's even more vulnerable to the informal cross-border smuggling” than state-level prohibitions, Caulkins’ “guess [was] if it's only a municipality doing the ban and the municipality next door has not,” access to vapor products would continue.

- After the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found vitamin E acetate to be a contributor to instances of vapor-associated lung injuries, state lawmakers passed a law in 2020 increasing WSLCB authority over cannabis products, including vapor items, which agency staff implemented through rulemaking that year.

- Reasoning that “when a municipality implements a product ban, that's even more vulnerable to the informal cross-border smuggling” than state-level prohibitions, Caulkins’ “guess [was] if it's only a municipality doing the ban and the municipality next door has not,” access to vapor products would continue.

- “Has the cannabis industry already been changing its marketing practices including trying to pioneer new markets...And if so, can we stop it?” (audio - 2m, video)

- Caulkin’s immediate response was “I think we've seen some steps in that direction, but the big steps will wait for there to be large enough corporations to…have a strategic interest in changing the whole market.” He suggested that “a hundred small and medium size companies that are…$50 million in sales or below” would lack the nationwide influence, and any “benefit of that would be spread across all 100 small companies.” The possibility increased if there were a “smaller number of very big companies,” but Caulkins saw no way to stop it as “we have a First Amendment freedom of speech protection that the Supreme Court interprets as applying to commercial free speech.”

- “What would happen if Washington implemented a ban on vaping products, [and] Oregon did not initially, but then it followed later?” (audio - 2m, video)

Information Set

-

Presentation - v1 (Sep 23, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - UW ADAI

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 00 - Complete (55m 20s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 01 - Introduction - Bia Carlini (55s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 02 - Presentation - Introduction - Jonathan Caulkins (1m 58s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 03 - Presentation - For-Profit Legalization - Jonathan Caulkins (7m 48s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 04 - Presentation - Wholesale Prices - Jonathan Caulkins (5m 9s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 05 - Presentation - National Legalization - Jonathan Caulkins (5m 5s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 06 - Presentation - Frequency of Use - Jonathan Caulkins (5m 50s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 07 - Presentation - Intensity of Use - Jonathan Caulkins (4m 33s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 08 - Presentation - Prohibitions - Jonathan Caulkins (15m 5s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 09 - Questions (38s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 10 - Question - Banning Vaping Products in WA (1m 58s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 11 - Question - Substance Substitution - Jonathan Caulkins (3m 13s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 12 - Question - Municipal Product Bans - Jonathan Caulkins (1m 25s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Audio - UW ADAI - 13 - Question - Strategic Market Manipulation - Jonathan Caulkins (1m 45s; Sep 19, 2022) [ Info ]

-

-

UW ADAI - Symposium - 2022 - General Information

[ InfoSet ]

-

Agenda - v1 [ Info ]

-

Sign In Sheet - v1 (Sep 16, 2022) [ Info ]