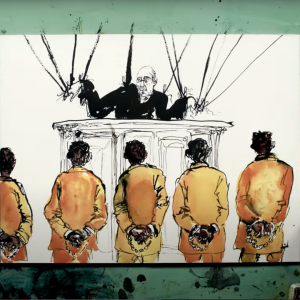

A history of racial discrimination in the American drug war and Washington state’s legal industry was described by a task force member, guest presenter, and commenters from inside and outside the industry.

Here are some observations from the Monday December 14th Washington State Legislative Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis (WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis) public meeting. In this summary, we focus and expand on a “History of Racism in Cannabis Policy and Enforcement” presented to task force members.

My top 3 takeaways:

- Evidence of racial disparities in the criminal justice system had long been observed, particularly during enforcement of cannabis prohibition.

- Nationwide, cannabis use rates by Black Americans stayed close to their White counterparts yet Black Americans were arrested at a rate three and a half times higher, according to the Brookings Institute. A variety of organizations had outlined racial discrimination around both cannabis and wider drug prohibition policing.

- A fact sheet about disparities nationwide among cannabis arrestees was created by the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

- The Drug Policy Alliance maintained a website on Race and the Drug War.

- Check out the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sponsored project, The War on Marijuana in Black and White.

- Some organizations that documented the racist past of the American drug war include History.com the Foundation for Economic Education, and the Collateral Consequences Resource Center.

- There was evidence of disparities in American judicial sentencing and incarceration around drug laws as identified by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.

- Academic literature and books document a pattern of racially-focused cannabis policing:

- The Colors of Cannabis: Race and Marijuana

- Reefer Madness: Sex, Drugs, and Cheap Labor in the American Black Market

- The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

- Something's in the air: race, crime, and the legalization of marijuana

- Between the World and Me

- Until We Reckon - Violence, Mass Incarceration, and a Road to Repair

- Marijuana Legalization in Washington State: Monitoring the Impact on Racial Disparities in Criminal Justice

- Racially disparate policing around cannabis was also evident outside the U.S. in the United Kingdom, Canada, and worldwide. Even police associations such as the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP) and the National Police Foundation had acknowledged the problem.

- In enacting the Initiative 502 cannabis licensing process, the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) faced broad accusations that staff had discriminated against non-White license applicants and disenfrancised communities of color from having the opportunity to participate in a legal industry after bearing the brunt of enforcement under cannabis prohibition. Following passage of HB 2870, Washington state cannabis social equity legislation signed into law on March 31st, WSLCB committed to scheduling a series of engagements with communities of color. The agency began by coordinating with the Washington State Commission on African American Affairs (CAAA), then contracted with Cultures Connecting to assist in facilitating the events which took the form of three virtual gatherings on September 29th, October 5th, and October 12th.

- The WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis created by HB 2870 hosted its first meeting on October 26th where members introduced themselves before discussing the task force bylaws and operating principles and disproportionately impacted areas.

- The task force got a late start due to the coronavirus pandemic, missing the deadline for their first report to the legislature. Task force staffer Christy Curwick-Hoff noted the social equity program to be defined by the task force and implemented by WSLCB would be “in existence from December one of [2020] through July 1st, 2028.” But the task force itself was scheduled to sunset on June 30, 2022 as defined in section 5(12) of the session law. Hoff previously questioned “whether that timeline should be extended because of the delay.” Rebecca Saldaña, Senate majority appointee to the task force, previously voiced an interest in promoting legislation to ensure the group had sufficient longevity.

- Nationwide, cannabis use rates by Black Americans stayed close to their White counterparts yet Black Americans were arrested at a rate three and a half times higher, according to the Brookings Institute. A variety of organizations had outlined racial discrimination around both cannabis and wider drug prohibition policing.

- Task force members, guests, and commenters unpacked some of the History of Racism in Cannabis Policy and Enforcement.

- Task force Co-Chair Paula Sardinas began by speaking to the importance of understanding the “history of racism in cannabis prohibition and their lasting impacts that we see today.” She expected the conversation would be “passionate” and asked everyone to “actively listen” (audio - 1m).

- Read the Staff Summary of Background Information on Arrest Inequities provided to task force members.

- Sardinas offered detailed testimony on November 30th about her motivation in supporting social equity at WSLCB as CAAA had seen “structural racism as the underpinning of how a lot of agencies and policies work in Washington State.” WSLCB had “become a suspect” of this manner of discrimination but seemed to be “willing to do the right thing when given the tool,” she said (audio - 15m, video).

- Jason Clark, a Credible Messenger Justice Center Equity and Justice Advocate (audio - 3m, audio - 15m, Presentation). Clark said he “grew up in poverty” and part of his presentation would cover “the way we’ve been impacted by the war on drugs.” He had experienced expulsion from school and incarceration at age 18 after selling drugs as a way to “change the trajectory of my financial future.” Even after serving his sentence, Clark saw “that connection to the criminal justice system proved to be a barrier for me.” His work with Credible Messenger broadly dealt with “capacity building and technical assistance for different leaders who’ve been impacted by systems.”

- Clark presented on:

- “Historical context...specifically around the impacts on Black and Brown communities.”

- “The impact of diversity and ownership.”

- “Some successful program examples and the barriers that they’ve faced.”

- A “review on data and enforcement.”

- Clark framed his presentation with an award winning video by Jay-Z and the Drug Policy Alliance which outlined how the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush “doubled down on the war on drugs,” significantly incentivizing drug sentencing and funding prison expansion to accommodate the resulting offenders through policies like the Rockefeller Drug Laws in New York. The American prison population “grew more than 900%” largely from Black and Hispanic communities. A recent trend towards legalization made similar activities to grow or sell cannabis “celebrated” in some states even as “most states still disproportionately hand out mandatory sentences to Black and Latinos with drug cases.” Legal states had seen “venture capitalists migrate to these states...but former felons can’t open a dispensary” and records in New York City---which had decriminalized cannabis possession in 2014---showed that disproportionality in possession citations endured, according to the video.

- Clark asserted that those impacted by cannabis prohibition should be included in Washington State’s legal industry “in an equitable fashion” as he highlighted signs of economic fallout felt in communities undergoing disproportionate enforcement. He stated that the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was a prime example of inequity being perpetuated by policy choices, noting that his grandparents' home in Detroit purchased through FHA in 1949 “isn’t worth a dime more” than the original value of $11,000. The absence of equity had other “disparate connections to systems,” Clark indicated, such as education and employment opportunities, and those without these avenues for growth “are more likely to be incarcerated.”

- However, Clark suggested task force members had an opportunity to remedy one area of unequal treatment by enabling cannabis equity license applicants to be “strategically mentored through capacity-building and developed into” successful business owners.

- Considering “diversity in ownership,” Clark told task force members to review the presentation notes he’d prepared for Washington-specific data on cannabis arrests, as the arrests were “incredibly disparate” against Black and Hispanic populations. Amongst owners of cannabis retail licenses, he noted “we see that same inequity” where more licenses were owned by White men as compared to their proportion of the state population.

- Beyond a stake in the cannabis industry, Clark asked “what about Black and Brown populations impacted by the war on drugs?” He noted that the cannabis market was forecast to hit $75 billion by 2030 and communities which had disproportionately suffered under prohibition wouldn’t experience true equity until policies “reach into the communities that have been impacted by incarceration based off of the war on drugs and especially cannabis sales.”

- Turning to the WSLCB implementation of a social equity program, Clark said Washington should “pay attention to what’s happened in other states” on social equity in order “to develop something that can...create a standard of success.” He reviewed several equity programs in California cities:

- In Oakland, among the first municipalities to prioritize equity, Clark indicated that the City hadn’t achieved the desired impact on their cannabis sector to date.

- In Sacramento, the City’s equity program had resulted in several businesses being approved in recent months, Clark reported. That program didn’t consider “applicant resources” in its evaluation, another factor which worked against applicants in areas harmed by cannabis prohibition, Clark explained. Despite good intentions, “less than five of” 29 new businesses were from communities of color, “and none of them were Black communities,” he said. While Sacremento’s program “applied the right mixture of capacity building resources, it’s obvious they failed in the equity as a program outcome for their communities.”

- Other jurisdictions with equity programs enacted or under development included Denver, Colorado and the State of New Jersey.

- Christopher Poulos, Washington Statewide Reentry Council Executive Director and task force member representing the Washington State Department of Commerce (audio - 9m, audio - 4m). Poulos said his input came as “a formerly incarcerated person” and law professor who had taught a class on drug war history “going back through the 1800s to today” which covered “how cannabis prohibition was developed” and the ensuing impact “on Black and Brown communities.”

- Poulos spoke to his history as a cannabis felon who subsequently graduated from law school before starting to “represent youth facing criminal charges.” He found that the individuals he represented on drug charges were invariably “Black, Brown, or from generational poverty, or all of the above.” From this, Poulos had come to know that “laws are simply not enforced the same way across the board.”

- Going back over a century earlier, Poulos said that even after the abolition of slavery in the U.S. “not being employed could get you arrested” which led to “exclusion from voting” and other rights and privileges, meaning “the continued control of Black and Brown people” through public policy. He commented that Harry Anslinger, an early federal official widely called America’s first Drug Czar, used racism frequently and unapologetically in advancing and enforcing drug prohibition.

- While the U.S. had a “public health approach” to drug use at the beginning of the 20th century, Poulos noted, “all of that changed and this was not accidental this was a very targeted, racist system that began way before [President Richard] Nixon’s or Reagan’s war on drugs.” He pointed out that America’s drug war included “alcohol prohibition, drug prohibition, the crack epidemic versus how we’re now treating the opioid epidemic.” As the latter had a wealthier, Whiter user demographic “now suddenly there’s an interest in the public health approach that we never saw before.”

- Poulos then quoted senior Nixon adviser John Ehrlichman, who said in 1994, “we knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

- Poulos remarked that a message that “drugs are bad, just don’t do them” was often tempered by individuals’ experience “with the policies” of drug prohibition. While one could say “the war on drugs has failed,” a fuller study of history led to a realization that “there was never actually a war on drugs, there was only a war on people, and that war targeted” communities of color “and the poor.” He said policies like stop and frisk were “simply not implemented in affluent White communities, or even White communities generally.” The resulting “disparate enforcement techniques” became self-fulfilling criminal statistics used to rationalize even stronger policing, Poulos explained. “We’re not over the hurdle,” on confronting racist drug enforcement practices “by any means,” he cautioned.

- Read Poulos’ research paper, The Criminalization of Addiction: Privilege and Recovery. He was unanimously re-appointed to lead the Reentry Council on September 30th.

- Poulos subsequently stated that WSLCB rules on criminal history checks for applicants “targeted and impacted...the people who are very most impacted” by disparate enforcement of cannabis prohibition resulting in them being “pretty much excluded” from the legal industry “for a minimum of ten years.” Poulos believed that to “even say that we’re working on this” meant that opportunities for those with criminal records to apply successfully had to be addressed “head on.” Clark called attention to ban the box legislation to remove disclosure of an individual’s criminal history from employment applications as being one way to “focus on the capacity-building of people who’ve been impacted” by the criminal justice system.

- Sardinas found their presentation “powerful” and thanked both for memorializing “in your document what the community has been saying for years.” She then opened the event up to comments from attendees.

- Baljit Bassey (audio - 6m). Bassey reported that he’d twice applied for a cannabis license and “had trouble” because sources of capital for his business were limited, as were available locations for a licensed premise. The process led to “depression and substance use” for him as well as an arrest “and losing the shop” before ever opening. Bassey “ended up with nothing” and hoped his experience could illustrate problems with “how the structure is laid out.” Sardinas asked him to send his comments in writing due to connection difficulties and suggest anything “that would have helped” him during prior application attempts.

- Peter ManningBlack Excellence in Cannabis (BEC) Co-Founder (audio - 6m). One thing Manning wanted the task force to “look at is why we are all here.” He said he and BEC Co-Founder Aaron Barfield had identified “an issue with Black people in the cannabis industry” as licensing had been unfairly “lopsided.” “Social equity is good,” he said, “but somebody needs to pay the price for how they affected our community.” Manning told the group that “the narrative that [WSLCB is] trying to push is as if Black people were too stupid or finanicailly inept to get a store. That’s not true.” He suggested that even if applicants for social equity licenses were successful they’d still “have the same overseers that made it difficult for Black people to get involved in the first place” and that the agency needed “get rid of the cancer, you can’t put a BandAid on cancer.” Manning warned, “They’re just going to come up with a good way to design to take it from us in the future if we don’t get rid of them.” Sardinas assured everyone that “I’m committed to the cause that is equity for the Black, Indigenous, and people of color community, I’m committed to working with the task force and making sure we collectively make the changes that are necessary, including if there need to be changes at a state agency. We are doing this work in earnest.” She added that the group wouldn’t “shy away from the difficult work.” Co-Chair Melanie Morgan gave her assurance that the task force would keep the cannabis history they’d learned in mind and credited Barfield for “speaking his truth” and raising the issuein the media. She asked Manning to follow up with her legislative office “in terms of the LCB’s structure” believing it was fair for the task force to question “is this the right team to carry out the recommendations that the task force will be putting forward?”

- Manning and Barfield aired their concerns with the Board in October and December 2019 before going over discrimination allegations with board members directly on January 20th.

- Manning testified in HB 2870’s senate hearing and commented during the first and third BIPOC sessions, the October 26th WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis meeting, and a work session with lawmakers on December 4th.

- Paul Brice, Happy Trees Owner (audio - 3m). Brice said he found WSLCB decision making took away “any Black minorities’ ability to advertise or have a voice” as he’d been fined for “every non-advertising violation.” He commented that Enforcement officers “just found a reason to try to target me and make sure I didn’t have no freedom of speech.” Brice believed the ability of cannabis businesses to voice “what it is that, you know, we need support or we need help” and advertise “what has happened” to minorities in the cannabis market without regulatory penalization was a component of good equity policy.

- Task force Co-Chair Paula Sardinas began by speaking to the importance of understanding the “history of racism in cannabis prohibition and their lasting impacts that we see today.” She expected the conversation would be “passionate” and asked everyone to “actively listen” (audio - 1m).

- Outside the work of the task force, a series of efforts were underway to undo or lessen the impact of cannabis prohibition, wider drug prohibition, and police brutality.

- Any next steps for HB 2870 would be up to the Legislature which hosted cannabis work sessions in the Senate and House on November 30th.

- Cannabis Prohibition

- In 2018, City Attorney Pete Holmes and Mayor Jenny Durkan went to court to secure a motion to dismiss cannabis possession charges the City of Seattle had made from 1996 to 2010.

- In 2019, Governor Jay Inslee announced the Marijuana Justice Initiative, a special pardon program for cannabis misdemeanors. In addition, a law was passed in May 2019 allowing for easier vacation of multiple cannabis misdemeanors.

- HB 1019, which would legalize residential cannabis cultivation by adults, was prefiled ahead of the 2021 legislative session. BEC supported the concept in their presentation on cannabis equity, whereas the Washington Association for Substance Abuse and Violence Prevention (WASAVP) opposed the predecessor bill.

- The Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on December 3rd, the first time either chamber of the Congress had supported the removal of cannabis from the federal Controlled Substances Act. However, the odds of the bill passing the U.S. Senate and being signed into law were reportedly slim.

- Policing and Other Reforms

- Treatment First WA is “a coalition of experts and community leaders who support replacing failing drug laws with a public health approach – treatment, recovery, and education.” The group attempted to get a measure decriminalizing personal drug use on the ballot in 2020 but switched to a legislative campaign for 2021.

- Oregon's Measure 110, a similar possession decriminalization measure, was passed by voters on November 4th.

- According to TalkingDrugs.org, Mexico’s “model of decriminalisation is codified in the country’s laws through statutory reforms, and was introduced in 2009, with Ley General de Salud (General Health law). In 2018 the Mexican Supreme Court ruled the prohibition of possession of cannabis for personal use and cultivation of cannabis was unconstitutional.” At publication time, Mexican lawmakers had been delayed in meeting a court deadline to pass cannabis legalization legislation and received an extension through April 2021.

- Governor Jay Inslee asked state agencies to consider equity in their budgetary decisions for 2021 as part of his agenda for the issue. The new Washington State Office of Equity had a proposed budget of $2.5 million along with a staff of eight. The Office could potentially take over responsibility for staffing the WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis.

- In 2018 voters adopted Initiative 940, the Police Training and Criminal Liability in Cases of Deadly Force Measure, which required that the State “create a good faith test to determine when the use of deadly force by police is justifiable, require police to receive de-escalation and mental health training, and require law enforcement officers to provide first aid.” The Legislature subsequently modified the initiative, leading to some supporters “raising concerns that state officials are rushing through the implementation process.” Inslee’s office organized a Governor’s Task Force on Independent Investigations of Police Use of Force in 2020.

- SenatorJamie Pederson, Chair of the Washington State Senate Law and Justice Committee (WA Senate LAW) announced support for further dismantling racism in policing by asking committee staff for potential legislation on topics such as:

- Prohibiting the use of chokeholds.

- Prohibiting law enforcement agencies in our state from accepting surplus military equipment.

- Requiring the use of body cameras statewide.

- Prohibiting law enforcement officers from covering their badge numbers while on duty.

- Requiring state collection of data on police use of force.

- Strengthening de-escalation and anti-bias training for law enforcement officers.

- Strengthening the decertification process so that law enforcement officers who are found to have used excessive force lose the ability to work in law enforcement.

- At the September 25th CAAA meeting, Representative Debra Entenman discussed the “African American and member of color caucus” agenda which included “police reform in the first 60 days” of the 2021 legislative session (audio - 3m).

- Washington House Democrats established a Policing Policy Leadership Team which previewed legislative policing reforms on November 30th.

- Leading up to the 2021 session, Task Force Co-Chair Melanie Morgan was re-elected Deputy Majority Floor Leader and Chair of the Member of Color Caucus (MOCC). Morgan “will lead the 19-member MOCC as they seek to remove all barriers of racial discrimination through democratic processes, and to provide equity, access and opportunity for all communities of color.” The MOCC “represents a third of the Democratic Caucus” in the 2021 session, “the largest House Members of Color Caucus...ever in the history of the Washington State Legislature.”

- Treatment First WA is “a coalition of experts and community leaders who support replacing failing drug laws with a public health approach – treatment, recovery, and education.” The group attempted to get a measure decriminalizing personal drug use on the ballot in 2020 but switched to a legislative campaign for 2021.