Presenting a report on cannabis health and safety outcomes, staff detailed patterns and limitations in their data as board members asked about the findings and future WSIPP studies.

Here are some observations from the Monday September 11th Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) Board of Directors Meeting.

My top 3 takeaways:

- An original requirement of Initiative 502 (I-502) was review of legalization impacts in a series of reports from WSIPP, where research staff are overseen by a board of directors that includes several state legislators.

- In 2012, I-502 set aside “revenue for purposes that include substance-abuse prevention, research, education, and healthcare.” RCW 69.50.550 mandated that WSIPP conduct cost-benefit analysis of cannabis laws. Reports executed through contracts with the Washington State Health Care Authority (WA HCA) and their Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery (DBHR) had dealt with I-502 and cannabis legalization. Other WSIPP reports on cannabis subjects have been mandated through separate legislation.

- Prior WSIPP publications on cannabis include:

- Legalization of Recreational Marijuana in Washington: Monitoring Trends in Use Prior to the Implementation of I-502 (2013)

- Preventing and Treating Youth Marijuana Use: An Updated Review of the Evidence (2014)

- I-502 Evaluation Plan and Preliminary Report on Implementation - First Required Report (2015)

- Updated Inventory of Programs for the Prevention and Treatment of Youth Cannabis Use (2016)

- Employment and Wage Earnings in Licensed Marijuana Businesses (2017)

- I-502 Evaluation and Benefit-Cost Analysis - Second Required Report (2017)

- Measuring Youth Cannabis Use in Washington State (2019)

- Suppressing Illicit Cannabis Markets After State Marijuana Legalization (2019)

- The WSIPP Board of Directors includes members of “the state legislature, executive branch, and the academic community” who govern agency actions, hire the WSIPP Director, as well as reviewing and “provid[ing] oversight for WSIPP’s projects.”

- WSIPP board members and staff (audio - 2m).

- Board Co-Chair Senator Chris Gildon (R)

- Board Co-Chair Representative Larry Springer (D)

- Senator Andy Billig (D)

- The Evergreen State College President John Carmichael

- Western Washington University (WWU) Political Science Department Associate Professor Kate Destler

- Washington State Office of the Governor (WA Governor) Executive Director of Policy and Outreach Rob Duff joined the board (audio - <1m).

- University of Washington (UW), University Analytics and Institutional Research Assistant Vice Provost Erin Guthrie

- Guthrie replaced Planning and Budgeting Vice Provost Sarah Norris Hall (audio - <1m).

- Representative Cyndy Jacobsen (R)

- Washington State Senate Committee Services Director Kim Johnson

- Senator Marko Liias (D)

- Washington State University (WSU) School of Economic Sciences Associate Professor Bidisha Mandal

- Representative Timm Ormsby (D)

- Washington State House of Representatives Office of Program Research Director Jill Reinmuth

- Representative Suzanne Schmidt (R)

- Schmidt was appointed to the board by the Washington State House of Representatives (WA House, audio - <1m).

- Senator Mark Schoesler (R)

- Washington State Office of Financial Management (WA OFM) Director David Schumacher

- WSIPP Research Manager Nate Adams

- WSIPP Director Stephanie Lee

- WSIPP Associate Director for Operations Catherine Nicolai

- WSIPP Senior Research Associate Amani Rashid

- WSIPP Associate Director for Research Eva Westley

- Westley and Rashid briefed lawmakers on development of the report on March 9th.

- Schoesler, Ormsby, and Johnson attended remotely. Liias and Reinmuth were not present at roll call.

- Senior Research Associate Amani Rashid gave a briefing to board members on I-502 and Cannabis-Related Public Health and Safety Outcomes.

- Lee walked the board members through Rashid’s experience since joining WSIPP “in May of 2020…she has also been leading our evaluation of Initiative 502.” She said the Institute was “about halfway through that timeline” for evaluation of I-502 impacts that was required by the initiative, and explained “we’re excited to hear” details from five reports Rashid’s team published the previous week (audio - 2m):

- The third required report on the impact of I-502 and legal cannabis

- The Relationship Between Initiative 502 and Reported Substance Use

- Licensed Cannabis Retail Access and Traffic Fatalities

- Initiative 502 and Cannabis-Related Convictions

- Licensed Cannabis Retail Access and Substance Use Disorder Diagnoses

- Rashid elaborated that besides releasing the third of four mandated reports, staff had published a 10-Year Review of Non-Medical Cannabis Policy, Revenues, and Expenditures in June. She said the earlier report “highlights major regulation and policy that ha[d] passed in the last ten years,” along with summarizing “revenues and expenditures going in and out of the dedicated cannabis account over the last decade.” However, her presentation would “not be about that,” Rashid noted, instead centering on “outcome evaluation,” considering how legalization and retail sale “relate to cannabis possession, convictions, reported substance use, substance use disorder diagnoses, and fatal traffic crashes.” These were topics that “f[ell] under the scope and purview of the assignment,” and which she could analyze “data from these outcomes.” Rashid said for “each outcome we assess the information for that outcome,” with data coming “from all over the place,” both local and national, “so we could focus on outcomes within the state” (audio - 3m).

- Possession Convictions (audio - 6m)

- “We describe how trends in cannabis possession misdemeanor conviction rates have evolved after legalization,” Rashid told the board, as “before Initiative 502, possession of any cannabis was a crime,” but “overnight, up to 30 grams of possession is now legal...this is directly affected by the law.” Utilizing a WSIPP “in-house” Criminal History Database, Rashid’s team evaluated "really detailed case records" between 2005 and 2019, including “roughly 120,000” cases of cannabis possession misdemeanors. She commented they could “look at not only outcomes for legal age adults 21 and over, but we also have information on those ages 12 through 20.”

- “We study the male and female population separately for a number of reasons,” Rashid remarked, “but a primary one being that their levels are really different.” She said prior to I-502, conviction rates for cannabis possession had been much higher for males than females, and “after initiative 502 goes into effect…rates dropped to essentially zero.”

- She noted that prior to enactment of I-502, possession convictions had already started to decline “since about 2009.” Rashid speculated on the reasons for this trend, pointing out:

- “One of them would be that Seattle and Tacoma…deprioritized cannabis possession in the years before…this time period.”

- “Another one could be that in anticipation of Initiative 502 passing, law enforcement and prosecutors could have started de-prioritizing cannabis possession.”

- “We still [did] see that sharp significant drop in conviction rates after…limited possession was legalized.”

- Looking at those same convictions for adults aged 18 to 20, Rashid found a significant decline in this age range, though again the conviction rate was higher for men than women. There was “about an 84% drop in the average conviction” for this age group, even though possession wasn’t legalized for them, and she said “many reports of interviews with law enforcement and prosecutors indicate that with initiative 502, came a deprioritization of limited cannabis possession enforcement across the board.”

- For minors between ages 12 and 17, “notably rates of conviction [were] just much lower among these groups, even prior to initiative 502,” particularly for female offenders, she stated, but since the initiative was enacted, “It did seem to go down a little.” But for male juveniles, “the average monthly conviction rate before Initiative 502 is about four per 100,000 population, and then after it dropped to two, so you still see a 50% reduction.”

- “Overall we're finding…substantial declines in, in cannabis possession conviction rates,” Rashid explained, and “other studies have looked at arrest rates and have seen similar results and now we're seeing that with convictions as well.” The data showed that this change in I-502 had achieved “substantial drops, not just for legal age adults, but also those under the age,” she said.

- “We describe how trends in cannabis possession misdemeanor conviction rates have evolved after legalization,” Rashid told the board, as “before Initiative 502, possession of any cannabis was a crime,” but “overnight, up to 30 grams of possession is now legal...this is directly affected by the law.” Utilizing a WSIPP “in-house” Criminal History Database, Rashid’s team evaluated "really detailed case records" between 2005 and 2019, including “roughly 120,000” cases of cannabis possession misdemeanors. She commented they could “look at not only outcomes for legal age adults 21 and over, but we also have information on those ages 12 through 20.”

- Reported Substance Use (audio - 2m)

- Rashid reported leveraging National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data comparing substance use—including cannabis—between Washington to other states that didn’t legalize, to see “if average rates in Washington changed after Initiative 502 relative to before, compared to other states.” She mentioned that they also looked for changes “before and after retail sales started in July 2014,” adding that this was a dividing line in legal access, adding that “studies out of other states have found that actually the advent of retail tends to be a stronger predictor of changes than actually legalization itself.”

- Looking at Washington state in comparison to “states with similar economic conditions, demographic conditions, [and also] states that had similar average rates before legalization,” Rashid stated, the survey showed “in Washington rates of reported use…have been slowly climbing over time, well before legalization started, but several other states, see the same pattern.” She concluded NSDUH provided “no evidence that reported cannabis use changed in Washington after 502, or after retail, relative to similar states,” nor were there changes in “reported alcohol, cigarette, or other substance use generally.”

- Retail Access (audio - 2m)

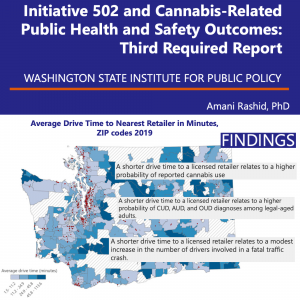

- Accounting for the "slow rollout" of retail stores beginning in July 2014, Rashid remarked this “might hide some of that real impact” in cannabis use, so her team looked closer. Moreover, “access [was] different across regions, not everyone has the same access across the state,” she observed. “In this study, we measure access, as the average drive time to the nearest retailer for the average resident in a geographical unit,” Rashid said. She continued, telling the board “what we did for each zip code, is we got information” to figure out if “this is roughly where people live, on average how far do you have to drive to get to a retailer?” An “average resident of the zip code in Thurston County, doesn't really need to drive more than 10 minutes to access a retailer,” Rashid reported, whereas in “Franklin County or Ferry County…the average resident needs to drive at least 45 minutes to get to retailers.”

- Rashid mentioned accessibility analysis hadn’t covered tribal retailers, since “we just don't have information.”

- Questioning if “reported cannabis use differ[s], do other related outcomes differ” based on retail access, Rashid acknowledged that retail licensing laws were partially based on population. She said their analysis had attempted to account for “regionality,” as well as changes over time: “we're not only taking advantage of comparisons across space…we're able to look within that same spot as it became more accessible” (audio - 1m).

- Comparing average drive time to retailers with reported adult cannabis consumption data from the Washington State Department of Health (DOH), Rashid said the research team wasn’t “looking at roll out…we are looking, as retail becomes more accessible is reported use changing (audio - 1m). She commented that when looking at information from 2014 to 2019, “about 11% of adults are reporting past month use over this sample, and about four percent of adults, on average are reporting heavy past month use over the sample period.” Shorter drive times to retailers appeared to relate to heavier use—defined as cannabis use on at least 20 days in the previous 30 days—though “it's a pretty modest relationship. A 50% reduction in drive time, so if you halve the drive time we see increases or higher probability of reporting half past month use by six percent, and heavy past month use by 8.6%” (audio - 1m).

- In 2022, the Washington State Health Care Authority (WA HCA) Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery (DBHR) published Location Matters: Access, Availability, and Density of Substance Retailers after some researchers expressed concern that individuals’ proximity to cannabis retailers could be an indicator of use.

- At time of publication, WSLCB staff had begun to review outlet density to advise lawmakers in line with requirements of SB 5080.

- Accounting for the "slow rollout" of retail stores beginning in July 2014, Rashid remarked this “might hide some of that real impact” in cannabis use, so her team looked closer. Moreover, “access [was] different across regions, not everyone has the same access across the state,” she observed. “In this study, we measure access, as the average drive time to the nearest retailer for the average resident in a geographical unit,” Rashid said. She continued, telling the board “what we did for each zip code, is we got information” to figure out if “this is roughly where people live, on average how far do you have to drive to get to a retailer?” An “average resident of the zip code in Thurston County, doesn't really need to drive more than 10 minutes to access a retailer,” Rashid reported, whereas in “Franklin County or Ferry County…the average resident needs to drive at least 45 minutes to get to retailers.”

- Substance Use Disorder Prevalence (audio - 5m)

- Rashid said the next stage of their report looked at how cannabis retail access could be correlated with a probability of receiving diagnoses of use disorders for cannabis, alcohol, and/or opioid use disorders. “These diagnoses can occur for, for a number of reasons,” she said, naming doctors appointments or emergency room admittance, but they were “generally measures of health care utilization.”

- According to Rashid, WA HCA and the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services (WA DSHS) staff provided WSIPP staff with data from “Medicaid beneficiaries.” She commented how “a lot of our analysis focuses on those ages 21 and older. We do briefly look at some underage populations.” Studying “Medicaid enrollees with a substance use disorder diagnoses quarterly…between the years 2010 and 2019,” Rashid conveyed that “alcohol use disorder diagnosis have been relatively stable over time,” while cannabis use disorder and opioid use disorder diagnoses had been “increasing over time [nationwide] and we do see that jump in around 2015.” There hadn’t been a clear reason for that jump, she said, but the underlying “diagnoses codes, how you define these diagnoses, did change, so that could be part of it.” Rashid told the group that excluding this spike didn’t account for all of the increases in cannabis use disorder diagnoses, however, “these are relatively rare diagnoses. They don't happen that much. So this is quarterly but even at an annual level of about…900,000 medicaid enrollees, ages 21 and older each year of that about 3.6 diagnoses of cannabis use disorder happen, about 4.5, for alcohol use disorder, and about 4.94 opioid use disorder, so not the most common outcomes.”

- Similar to access, the report indicated that a shorter drive time to a retailer could be “relate[d] to a higher probability of cannabis use disorder (CUD), alcohol use disorder, and opioid use disorder among legal aged adults,” said Rashid. “For example, a 50% reduction in drive time relates to a 2.3% higher likelihood of an annual cannabis use disorder diagnosies,” she stated, describing this as “relatively moderate also like the reported use” in surveys. Co-occurring diagnoses, like someone having both cannabis and opioid use disorders, also related to access, with Rashid describing how “about 50% of the time you get one of those co-occurring and about 10% of the time all three co-occur.” She noted this could be evidence to “indicate that those who use or misuse cannabis are more likely to use or misuse alcohol and opioids…to be clear though, this does not establish like, a cause and effect relationship. This doesn't tell us that cannabis use disorder caused it. We're not establishing a gateway effect with these results.”

- This analysis showed from the second report on I-502 from 2017 which “found no evidence that the amount of legal cannabis sales affected cannabis abuse treatment admissions.”

- Fatal Traffic Accidents (audio - 3m)

- Evaluating if “greater access predicts greater use,” Rashid’s team looked for “higher numbers of drivers involved in fatal crashes,” though “we cannot measure cannabis impaired driving. So…we don't know that, but we can look again at patterns and see if greater retail access predicts changes in the number of drivers involved in fatalities.” She described how “only about 50% of drivers involved in a fatal crash actually receive a blood test,” which meant “we actually only know that information relative to the 50% who got tested.” Therefore, Rashid qualified that “when we talk about THC prevalence we are not talking about all drivers, it is the subset who actually received a blood test.”

- Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC) data between 2008 and 2019 had indicated “a shorter drive time to a licensed retailer relate[d] to a modest increase in the number of drivers involved in a fatal crash,” said Rashid. She offered the example that “a 50% reduction in the average drive time to the nearest retailer predict[ed] about 46 more drivers involved in a fatal crash annually,” or a “5.5% increase in the number from those locales.” This data suggested shorter drive times could also be related “to a higher prevalence of drivers who test THC positive,” Rashid remarked. She stipulated that “delta-9[-THC] metabolizes pretty fast…it's a decent indicator of having somewhat recently used cannabis,” though that alone didn’t prove an individual was impaired, “actually, determining impaired driving is a lot trickier than just the blood test result.”

- I–502 included a driving standard of five nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood as per se proof of impairment, which was upheld by the Washington State Supreme Court in a 2022 ruling, though some voiced skepticism in this approach.

- “We were able to look at how retail access predicts prevalence of BAC [blood-alcohol content] and then co-occurring prevalence of BAC and THC in the blood,” said Rashid. While some studies indicated combining both substances “makes you more at risk of traffic fatalities,” she told the board that they hadn’t seen “evidence that retail access predicts higher numbers, or changes in either one, but the samples do get quite small…there's not that many drivers so it's hard to significantly detect those effects.”

- Having presented “a lot of information,” the takeaways for Rashid were that besides the immediate criminalization changes included in I-502, the legal status of cannabis wasn’t “significantly related to [use] changes, but when we focus on access we do see higher retail access relates to higher reported use, and subsequently associates with higher disorder diagnoses, and more fatal crash collisions.” She emphasized that “these are just relationships as we're talking about regulation of the market…we're not establishing cause and effect…we need more information on outcomes,” retailers, sales, and communities (audio - 1m).

- Looking ahead, Rashid noted that I-502 included required studies until 2032, and WSIPP staff would be looking at “reported adolescent use and school outcomes,” as well as “exploring more health care outcomes.” She commented that “we don't talk about direct economic impacts; or labor impacts; wages and employment within the industry…we're hoping to look into that side of the market for future reports” (audio - 1m).

- On September 20th, Washington State Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) staff described planning questions for a study of the economic impact from the cannabis market in 2024.

- Lee walked the board members through Rashid’s experience since joining WSIPP “in May of 2020…she has also been leading our evaluation of Initiative 502.” She said the Institute was “about halfway through that timeline” for evaluation of I-502 impacts that was required by the initiative, and explained “we’re excited to hear” details from five reports Rashid’s team published the previous week (audio - 2m):

- The Board of Directors raised questions about what Rashid covered, and limits of what they could infer about patterns in cannabis access, use, and misuse from the report.

- Jacobsen asked for clarification on the source data for substance use. Rashid replied it was from NSDUH survey data, and that last month cannabis use “didn't change significantly in Washington relative to other states” over the studied period (audio - <1m).

- When Mandal checked whether NSDUH information was broken down by gender, Rashid said “we can't subgroup if the samples get too small,” and she had only been able to compare states based on age groups (audio - 1m).

- Gildon inquired about the number of tribal retailers within Washington, but Rashid didn’t know (audio - <1m).

- In August 2022, WSLCB staff recognized the 21st tribal government cannabis compact, and indicated on September 13th that four more compacts were in development.

- Jacobsen wanted to know about regions Rashid’s team hadn’t been able to get residential data for (audio - 1m).

- Billig was curious if a change in the legal status of cannabis could have made respondents more willing to admit to use. “That is definitely a limitation,” Rashid admitted, “there's a lot of evidence that that could be…what's happening here” (audio - <1m).

- Asking about the “causal relationship here,” Destler guessed that populations with greater cannabis demand were more likely to attract retailers, which translated to lower drive times. Rashid emphasized that retailer placement wasn’t random, and agreed report “results are not causal and shouldn't be framed as causal, they're just relationships.” She remarked that the report did attempt to account for other factors and “we do examine how sensitive our results are” (audio - 2m).

- Jacobsen inquired whether meeting CUD criteria would predispose someone to want to live near a cannabis retailer. “I think intuitively that would seem to be a direction it goes,” yet “mobility could be a little limited” for many people, Rashid responded. Jacobsen also suggested retailers would attempt to locate “near a population with high levels” of cannabis use. Rashid emphasized that “this just says, where…there's greater access there is greater prevalence of cannabis use disorder diagnoses.” She found that “we control for socioeconomic indicators in a neighborhood, we controlled for population demographics, we do not control for health care access or potential for corresponding…things happening related to health care in the background.” Rashid’s example was opioid use disorder diagnosis, as over the period studied “there are a lot of like spikes in opioid use disorder outcomes,” meaning “if that is regionally where retailers are locating…we are not parsing that apart, this is just establishing fundamentally the correlation between” retail accessibility and outcomes (audio - 2m).

- Springer asked, “why would greater access affect 12 to 17 [year olds] more than 18 to 20?” Rashid hesitated to “speculate at this point, but…we're taking a step back and” preparing to study “the Healthy Youth Survey [HYS]. We want to better understand…cannabis use behaviors among youth and young adults.” She asserted that “surveying measures have become more sophisticated in trying to understand where underage use comes from…the hopes would be in the future, we can understand that behavior a little bit better” (audio - 3m).

- Springer was uncertain whether they needed more data. Rashid indicated that more analysis of existing data was needed, but “these results are not saying that 12 to 17 year olds have diagnoses and 18 to 20 don't. This is saying that 12 to 17 year olds are more sensitive, or are responding to access” to a greater extent than young adults.

- Destler guessed “12 to 17 year olds would be more geographically constrained” than young adults. Rashid speculated that being in college might have had an impact.

- Find out more from a WSLCB staff presentation of the most recent HYS responses in May 2022, and of young adult survey data in July 2022.

- Mandal wondered if the Medicaid information covered CUD as a “primary diagnosis” or secondary one. Rashid stated that all claims involving the condition were included (audio - 1m). Mandal then noted “claims data…could potentially be longitudinal. Are you looking at” whether repeated health care visits “counted multiple times or just one time?” Rashid responded “at this moment in time with these analyses you can see the same person multiple times…We are just counting the claims, the diagnosis code coming up (audio - 1m).

- Rashid elaborated “even if I'm not doing a causal analysis, I don't think I would use the word a ‘relationship’ between disorder and access. It's more utilization, because disorders sound like that it's a new diagnosis, and the more of a diagnosis you have the more access, which is not the case here.”

- Duff inquired whether CUD was a “generally new disorder” since cannabis legalization. Rashid said “the definition has been around, and that diagnosis code has been around for a long time. What could be happening though is…the doctor’s willingness to diagnose it ha[d] changed.” Because CUD data was dependent on both “your willingness to interact with the health care system,” as well as “the provider’s willingness to diagnose it, or knowledge of diagnosis,” Rashid explained, “we're not just looking at before and after though…it has to be that doctor behavior is changing systematically as access increase[d].” She suggested more information on “treatment seeking behavior, and other measures…like hospitalization or ER [emergency room] visits” could potentially “contextualize” and “better inform, why do we see this relationship” (audio - 2m).

- Mandal was curious if they could compare ER and outpatient treatment. Rashid was open to looking at that, but “at this moment in time, these are the only data we were able to acquire” (audio - 1m).

- “So 2014, Medicaid expansion happened,” Mandal remarked, resulting in a “humongous” amount of “additional beneficiaries who are different because they [were a higher] socioeconomic” demographic “compared to the original Medicaid.” Rashid called this a “great point,” and said they had a “flag” on their information “and we actually [were] looking at individual claimants. So, we were able to check the robustness of our results” (audio - 1m).

- Rashid reassured Jacobsen that they had a sufficient sample size, describing how limitations she mentioned involved “subsetting and subgroup analysis, that's where it becomes more challenging…I don't want to cut up the sample too much and have really small groups driving results” (audio - 1m).

- Billig had Rashid repeat cannabis use rates identified in the report (audio - 1m).

- Considering the decreased prioritization of some cannabis prosecutions, Billig pointed out “you said one of the possibilities that you heard was that this [was] a result of deprioritization even though it's still illegal.” He remembered a “rationale” behind I-502 “that I heard that made sense to me anecdotally was that with a regulated system there's not going to be a black market, so that it's going to be harder for young people to get…is there any evidence or any chance that, that could be a result?” Rashid expressed uncertainty as their analysis didn’t look into that since “measuring the illegal market is really hard, so we get a lot of questions about that and at this moment in time, that's not something that we can confidently speak to.” She shared that more focus went to a concern “that a legal retail market creates another supply chain and there would be those spillovers with this outcome; we didn't see huge changes” (audio - 2m).

- Westley added that WSIPP staff had looked into this question in 2019, but they concluded “it's super hard to measure and so the report led to a bunch of suggestions about monitoring, and what we could do to kind of get a better picture of that, but it is just really hard to know.”

- Jacobsen asked why women were being arrested less. Rashid noted that trend had been previously observed in other studies of gender and crime, and “we see that male populations…interact with the criminal justice system at much higher rates than the female population” (audio - 1m).

- Destler inquired, “could you use your measure of access” to “go back in time and see whether access in 2014 or 2015 predicts levels of disorder or usage in 2012 when there wasn't actually any [lawful] access” (audio - 2m).

- Rashid felt this was a “great idea.” She hadn’t done that kind of research, but acknowledged “you could look at pre [retail] levels within the community and see if it predicts a retailer opening in the community.” However the ability to parse data was limited “since licenses, like retailers, don't randomly locate - it's going to be such a challenge to get that cause and effect.”