Senators heard a status report on the social equity task force, concerns from past and prospective applicants, and a rebuttal from WSLCB staff on licensing decision making.

- WA Senate LBRC member Rebecca Saldaña was joined by the lead staffer for the Washington State Legislative Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis to brief senators on progress and potential follow up legislation.

- The first meeting of the task force was on October 26th; a second meeting was scheduled for December 14th.

- Rebecca Saldaña, Senate Democrat appointee to the Washington State Legislative Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis (WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis, audio - 5m, video).

- Saldaña acknowledged it “took a little longer” for the task force to get started but the group “had our first meeting, it was really grounding.” Lauding all who had so far participated, she said the group’s mandated report to lawmakers would be delayed and legislation "to help clarify the jurisdiction of the task force and to make sure that we have continued funding” was likely to be presented during the upcoming legislative session.

- Christy Curwick Hoff, lead staffer for the WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis (presentation, audio - 5m, video).

- Hoff, a Health Policy Advisor and staff to the Governor's Interagency Council on Health Disparities, said all 18 members on the task force attended the first meeting. She identified task force responsibilities and goals and reported “a lot of good community engagement” at their inaugural meeting.

- She said the task force would advise the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) “including, but not limited to, establishing the social equity program for existing retail licenses” as well as make recommendations to the legislature and governor on how to “promote equity in the cannabis industry more broadly.” Hoff indicated task force members were already contemplating “whether the social equity program should be expanded to look at different kinds of licenses in addition to” retail.

- Hoff said the council on health disparities had “a lot of experience working on equity and social justice issues broadly” although “the topic of cannabis is new to us.” She was learning about “the institutional racism that has existed in this industry to date so that we can redress those inequities as we move forward.”

- Due to their late formation, Hoff reiterated past acknowledgement that the task force wouldn’t meet their first deadline on December 1st. However, they would “be coming up with priorities and a revised timeline” for lawmakers in the near future, she said.

- Black Excellence in Cannabis members explained their experience pursuing WSLCB licensing and their ambitions for the social equity program, strengthened by testimony from a Co-Chair of the social equity task force.

- Aaron Barfield and Peter Manning, Black Excellence in Cannabis (BEC) Co-Founders (presentation, audio - 10m, video).

- Barfield began the group’s testimony by describing BEC’s work “fighting for inclusion for African Americans in Washington’s cannabis industry.” He said there was “less than one percent by African American ownership in the regulated cannabis industry...a shameful embarrassment to the state of Washington” and that a “more inclusive and diverse” industry offered both rectification and good policy.

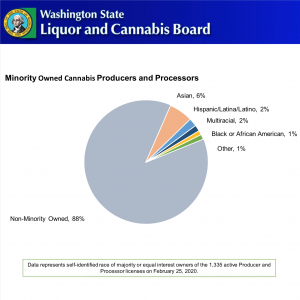

- WSLCB’s presentation claimed that the “self-identified race of majority or equal interest owners of the 483 active licenses on June 30, 2020” revealed 3% of retail owners identified as “Black or African American.” The corresponding survey of 1,335 producer and processor license owners indicated 1% African American ownership.

- Barfield introduced Manning to describe “what dispensary owners went through” during the merging of the recreational and medical markets in 2016 via SB 5052, when the agency opened a second application window.

- Manning explained that he and a partner, Jferrich Oba, applied for a business license in 2011 and believed they “did everything that we should have done and that we were required to do by law” in operating their Seattle-based medical dispensary. When retail cannabis was legalized by voters in 2012 and “the LCB got involved,” Manning reported that “a lot of medical patients suffered” and there was a “crackdown” on dispensaries from city officials, including social equity task force member David Mendoza. Manning said that he was told by city officials they would “face a penalty of $1,000 a day” if they continued operation but reassured that “LCB will most definitely grant you a license quickly.” As an applicant, Manning’s impression was that the agency “had every reason not to give us a license” and the licensing process was a “nightmare.”

- Barfield chimed in to say Manning’s situation reflected “all of the black owned dispensaries in all of Seattle” prompting Committee Chair Karen Keiser to ask how many “black owned medical cannabis stores” had been in Seattle. Barfield estimated “about 20-25%” of the city’s approximately 400 dispensaries had been owned by African Americans.

- Later, Barfield’s estimate was somewhat seconded by task force member Cherie MacLeod, City of Seattle Strategic Advisor and Marijuana Regulatory Program Manager (audio - 2m).

- Manning stated WSLCB staff “froze out black participation” when merging the medical and recreational markets between 2015 and 2016. He alleged that white applicants were forgiven for tax or application errors that applicants of color were not. Manning said he’d been given “misinformation” from WSLCB staff before eventually being informed the paperwork they’d provided “couldn’t be used for anything.” He connected with a business partner who was white and saw them “take it to the same people that had denied us” and receive a retail license “in record time.” Asked later why that partner’s paperwork would be accepted, Manning relayed a WSLCB representative’s response that the partner “cleared it up” with a simple conversation and “that’s why the paperwork became good.”

- “I personally believe it was by design,” Manning said, saying African American applicants had “completely right” applications rejected, “and then you take a white person with the same paperwork, and then they’re accepted.” He found it “crazy” for the State to study “why aren’t there any black people in the cannabis industry” as it seemed obvious that a WSLCB “licensing scheme” was the cause of the ownership disparity. Barfield commented that they’d brought their concerns to WSLCB for some time but that “a system of apartheid” remained in the 502 market.

- Manning raised the issue of discrimination by the agency in 2016. Barfield previously called out a “lack of social equity in Washington’s cannabis industry” to the Board in October and December 2019. BEC members discussed discrimination allegations with board members directly on January 20th, testified in HB 2870’s senate hearing, commented during all three BIPOC sessions hosted by WSLCB, and spoke during the task force’s first meeting on October 26th.

- Barfield was positive that “additional legislation” would be needed to supplement HB 2870, the law creating the social equity program and task force, “to build a real inclusive industry” which generated “huge” revenue for the State. Manning noted the “hypocritical side” of the issue, as African Americans had been disproportionately targeted for arrest when cannabis was illegal, but “now that it's profitable we’re excluded out of it.”

- Barfield began the group’s testimony by describing BEC’s work “fighting for inclusion for African Americans in Washington’s cannabis industry.” He said there was “less than one percent by African American ownership in the regulated cannabis industry...a shameful embarrassment to the state of Washington” and that a “more inclusive and diverse” industry offered both rectification and good policy.

- Sami Saad (audio - 8m, video). Former Owner of 12green, a Seattle dispensary.

- Saad claimed he was the only Muslim dispensary owner “in this field” and “African” rather than African American, making him unique within the state’s black community. He predicted he would “file a lawsuit against all those people put me through [sic]” his shop closure, while a white owned retail shop was permitted to open nearby. Saad said that while his dispensary should have made him a “category 1” applicant when the medical and recreational markets merged, WSLCB staff told him a missing Limited Liability Company (LLC) status meant he was “pushed away.”

- Saad expected that “meeting after meeting after meeting” was “not going to change anything” with WSLCB’s licensing.

- Saad faulted WSLCB for not making materials available in the Arabic language, and continued profiling by local law enforcement. As a medical patient, he hadn’t appreciated being required to “go and buy from somebody else.”

- During the December 2nd meeting of WSLCB’s Alcohol Advisory Council, Director of Licensing Becky Smith said the agency made sure “we are providing information in other languages” for their applications and agency website as a social equity improvement (audio - 5m). At publication time, that information was available in the English, Spanish, and Korean languages.

- Saad felt WSLCB Board Member Ollie Garrett “did not represent us” at the agency. He indicated Washington State Commission on African American Affairs (CAAA) Commissioner Paula Sardinas “never spoke to me again” following an initial introduction. Saad was concerned that he didn’t “want to be left all over” again.

- Saad alleged that WSLCB staff engaged in a bribery scheme among wealthier applicants, something he’d mentioned in public comments at the agency’s June 24th board meeting. Keiser asked that he provide the committee with any evidence of criminal behavior, and Saad offered hearsay about an eastern Washington licensee with no prior cannabis expertise securing a license.

- He also cited Shawn Kemp’s Cannabis as a business masquerading as minority owned while Kemp received “a percentage from certain people” to use his name and likeness.

- Kemp’s affiliation with the business has drawn some backlash from the public after the retailer announced Kemp as a co-owner before clarifying their own “statement should not have been released. As a result, it has caused great distraction to this store’s intention.”

- Saad restated that a lawsuit from himself, BEC, and others would target Director Rick Garza and challenge the agency’s practices which had the effect of disenfranchising minority license applicants. When Keiser asked Saad to conclude his remarks he tried to speak over her and was eventually muted.

- Saad was a regular critic of the WSLCB and the regulated marketplace, first speaking at the February 22nd Cannabis Equity in Our Community forum hosted by the City of Seattle and HB 2870’s senate hearing. He also gave remarks during all three BIPOC sessions as well as the task force’s first meeting.

- Paula Sardinas, CAAA appointee to and elected Co-Chair of the WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis (audio - 15m, video).

- Sardinas began with kudos to senate supporters of HB 2870, the task force’s enacting legislation, and acknowledged Black Excellence in Cannabis brought the topic to the CAAA whose members subsequently voted to back the effort. She believed there was “a credible case where they’d been wronged by the LCB.”

- Sardinas sought to criticize biased licensing by WSLCB but clarified that “lumping the Board and the agency together” in this instance was “unfair.” She said the “licensing department...basically gave out misinformation” and that Director Rick Garza had become the focus of “legitimate, widespread concerns.” She questioned the agency’s ability to increase equity in the 502 market while behaving as “a policing agency" in contrast to "a regulatory mentality." Sardinas called out “a fundamental lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion that permeates the culture of the LCB.”

- While “adjudication” of the relative racism of government activities was not within CAAA’s authority, Sardinas conveyed the Commission saw “structural racism as the underpinning of how a lot of agencies and policies work in Washington State” and that WSLCB had “become a suspect” of this manner of bias. Among the agency's failings, she said were “not enough employees who identify as black or African American,” a “flawed” licensing process, and “inflexible” decision making.

- Despite institutional problems, Sardinas’ personal interactions with WSLCB showed her the Board was “honest” and “willing to do the right thing when given the tool,” citing the agency’s equity engagement events as an “emotional” example of this. Nonetheless, she saw police brutality around the nation as “egregious” examples of the same discrimination the panelists before her had experienced from cannabis regulators.

- The African American community didn’t “want anything for free,” Sardinas remarked, “they want fairness.” While grateful for the committee’s attention, she believed the situation was “LCB’s mess to clean up.”

- Aaron Barfield and Peter Manning, Black Excellence in Cannabis (BEC) Co-Founders (presentation, audio - 10m, video).

- Director of Legislative Relations Chris Thompson provided a WSLCB perspective on the history of cannabis legalization and indicated positive steps the agency was taking in response to criticisms before specifically rebutting claims presented to senators.

- Chris Thompson, WSLCB Director of Legislative Relations, (presentation, audio - 15m, video).

- Thompson defended the agency. He explained that staff recognized a racial disparity in licensing, but highlighted the largest identified gap “between the licensee base and the population of the state” was among the Hispanic population who were “about 13% of the state and about 2% of the retail licensees.” He also noted Caucasian licensees were even more overrepresented among cannabis producers and processors. He reported that retail title certificate holders were a less disparate group of licensees but “were not able to open their businesses.”

- Thompson walked the committee through a history written by WSLCB about the merger of the medical and recreational marketplaces.

- Describing how “dispensary growth exploded” following the passage and partial veto of SB 5073 in 2011, the history asserts “U.S. Attorneys for Western Washington (Jenny Durkan) prosecuted few, perhaps emboldening dispensary operators.” At time of publication, Durkan served as Seattle’s mayor.

- The history emphasized WSLCB’s role implementing SB 5052 included a priority application system structured by lawmakers: “The Legislature created a three-tiered system for prioritizing applications for the new retail licenses. The first priority was defined by law as including those who met all four of the criteria set by the Legislature…”

- The history concludes with a note that “law enforcement and county prosecutors varied in their approach to the transition” and highlighted Thurston County Sheriff John Snaza who visited each unlicensed medical dispensary personally.

- Thompson touted equity outreach already undertaken by the agency and said there was an effort for "more nuanced and holistic assessments" of equity applicant’s criminal history than had been used in earlier application windows.

- Thompson explained that WSLCB was engaging with local governments to “explore ways of reducing the barriers” cannabis businesses face, potentially leading to the lifting of some regional bans or moratoriums.

- As the on-going pandemic continued to undercut local government revenues, the City of Everett voted to increase their allowed retail locations on October 14th and the Lynnwood City Council had begun exploring the possibility of ending their ban.

- Thompson then made a point of publicly addressing the specific case of discrimination raised by BEC. He said the agency was still looking at “what happened, was it proper, was it improper, and where do we go from here?” Thompson reported that Manning and Barfield’s application, for a proposed retail entity Cloud Nine, was being reviewed to “see where we would assess that at this point in time.” He attributed the prior change in the application’s priority status to “other applicants” who had made “a case for priority one status based on employment at” Manning’s former medical cannabis collective, Bella Sole. Thompson said a dispute emerged over who and how many people Bella Sole had employed which resulted in outstanding tax questions that ultimately compromised his application’s priority status. Thompson concluded that the Washington State Office of Administrative Hearings had adjudicated the Cloud Nine application and affirmed the lower priority status. Nonetheless, “we want to go back and review that,” Thompson said, to “address anything improperly done.”

- Barfield interjected that Thompson gave “the final reason” for the application’s denial but failed to tell the full story (audio - <1m, video).

- Turning to Saad’s application, Thompson said “he never did provide any documentation to support” a high priority status “and, as a consequence...didn’t receive a license.” He finished by affirming Garza had the “full confidence” of WSLCB on equity and other issues (audio - 1m, video).

- Saad interjected that he’d called WSLCB staff about his priority status “and they refused me.” He protested the agency “did not say the truth” before Keiser eventually asked for his audio to be muted a second time (audio - <1m, video).

- Wrapping up, Keiser credited Thompson’s “refresher course” on the history of Washington’s medical cannabis policies, and commended WSLCB’s “effort to change culture, it is not easy to change culture” (audio - 1m, video).

- Chris Thompson, WSLCB Director of Legislative Relations, (presentation, audio - 15m, video).

Information Set

-

Agenda - v0 [ Info ]

-

Agenda - v1 [ Info ]

-

WA CAAA - WSLCB 2020 Assessment Report (Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Incomplete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Incomplete (2h 3m 12s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Introductions (1m 9s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Welcome - Karen Keiser - continued (1m 32s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Social Equity in Cannabis - Rebecca Saldaña (4m 45s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 04 - Social Equity in Cannabis - Christy Curwick Hoff (5m 7s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Social Equity in Cannabis - Black Excellence in Cannabis (10m 7s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 06 - Social Equity in Cannabis - Sami Saad (8m 7s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Introduction - Mark Schoesler (31s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Social Equity in Cannabis - CAAA - Paula Sardinas (15m 24s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 09 - Social Equity in Cannabis - CAAA - Comment - Karen Keiser (1m 23s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 10 - Social Equity in Cannabis - WSLCB - Chris Thompson (15m 9s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 11 - Social Equity in Cannabis - WSLCB - Comment - Aaron Barfield (28s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 12 - Social Equity in Cannabis - WSLCB - Chris Thompson - continued (1m 22s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Social Equity in Cannabis - WSLCB - Comment - Karen Keiser (36s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 14 - Social Equity in Cannabis - WSLCB - Comment - Sami Saad (28s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Medical Cannabis - Introduction - Karen Keiser (43s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 23 - Medical Cannabis - Mary Brown (4m 32s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 24 - Medical Cannabis - Lukas Barfield (4m 23s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 25 - Cannabis Research Commission - Alan Schreiber (3m 48s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 26 - Cannabis Research Commission - Lara Kaminsky (2m 54s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Cannabis Research Commission - Question - Scope - Mark Schoesler (2m 48s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 32 - Wrapping Up - Karen Keiser (55s; Nov 30, 2020) [ Info ]

-