Task force members received a data briefing to assist in elaboration of qualifying criteria for cannabis social equity applicants residing in “disproportionately impacted areas.”

- University of Washington researchers provided a data presentation on areas disproportionately impacted by enforcement of cannabis prohibition to help task force members specify geographic zones of eligibility for prospective cannabis retail equity applicants

- The task force must recommend a clearer definition for disproportionately impacted areas, one set of qualifications for applicants to the social equity program at the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB).

- In the late afternoon during the first meeting of the task force, Co-Chair Melanie Morgan, representing House Democrats, introduced a “data briefing and discussion” about disproportionately impacted areas. She said the presenters, University of Washington (UW) Professor of Sociology Alexes Harris and UW graduate student Michele Cadigan, had assessed “cannabis-related convictions data and have offered to assist this task force with mapping convictions and other criteria” so that the group could “identify and define communities disproportionately harmed by this cannabis enforcement” (audio - 1m, video).

- Harris greeted the task force members, saying she’d been invited to help “think through data-related issues to identify the disparate impact areas” (audio - 23m, video).

- Harris said she and Cadigan were “researchers who care about social justice and equity, and we’re just here to support the task force in trying to figure out how you all want to define and clarify the focus of the equity program.” As a sociologist, Harris specialized in “social stratification and inequality” and studied “monetary sanctions, the fines and fees that people are sentenced to” by the criminal justice system. In 2017, she authored A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor.

- Cadigan said she studied “cannabis markets throughout the U.S.” with support from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy Research. In 2018, Harris and Cadigan published Becoming an Expert Cannabis Connoisseur: Toward a Theory of Moralizing Labor.

- Other equity programs. Cadigan first examined other legal cannabis jurisdictions’ “equity, or lack of, approach.” She noted:

- In California, whose voters backed legalization in 2016, “after the measure was implemented...they went back and established a statewide program” with the purpose of “ensuring that persons most harmed by cannabis criminalization and poverty be offered assistance to enter this industry.” She reviewed municipal programs implemented by Oakland, Los Angeles, and Long Beach, which all had some version of disproportionate impact areas.

- In Massachusetts, their 2016 legalization initiative “was the very first to explicitly call for a market that tried to repair harms done to communities of color.” Cadigan reported policymakers created a program requiring “black or Latinx...majority ownership” in “areas disproportionately impacted” and required a “positive impact plan.” Additionally, she explained, the state had a multi-tiered training program which covered ancillary businesses, management, and “business ownership.”

- In Illinois, Cadigan pointed out their 2019 legalization was the first accomplished via a legislature “with an explicit focus on racial equity” including creation of an equity program. She highlighted the City of Evanston’s reparations tax fund from cannabis sales as a way “to improve the black community in Evanston.”

- All the programs had limits “to be considered,” she argued, for instance “lag time” between applying and receiving licensure as well as financial, regulatory, and “real estate issues, too.” Cadigan said programs also saw “too many applications versus available licenses.”

- “the Washington equity program as outlined in the statute”

- Harris reported that Initiative 502 (I-502) in Washington drew support from people who recognized that “Washington’s cannabis laws are enforced disproportionately against African Americans.” Harris said Kathleen Taylor, former American Civil Liberties Union of Washington (ACLU WA) Executive Director, observed that cannabis prohibition before I-502 was “ineffective, unreasonable, and unfairly enforced, they have done much damage to civil liberties.” Harris framed the 2012 initiative’s broader intent as “redressing injustices for the African American community.”

- Harris credited Cadigan for leading their review of I-502’s impact on laws and regulation, and determined that existing Washington policy posed “legal barriers that bar access to populations with criminal records and low income individuals” making it “difficult to secure employment and ownership” within the regulated marketplace. Moreover, “it appears that there was a co-opting of the social justice movement, namely rhetoric suggesting I-502 would redress African Americans in Washington state, to justify ownership and employment to predominantly white individuals,” she stated.

- Harris spoke to the program’s requirements that qualifying social equity applicants may have resided “for at leave five of the preceding ten years in disproportionately impacted area[s], or have been convicted of a marijuana or cannabis offense, or [be] a family member of such an individual.” She described the program’s definition of disproportionately impacted area as “a census tract or comparable geographic area that satisfies the following criteria”

- (i) The area has a high poverty rate;

- (ii) The area has a high rate of participation in income-based federal or state programs;

- (iii) The area has a high rate of unemployment; and

- (iv) The area has a high rate of arrest, conviction, or incarceration related to the sale, possession, use, cultivation, manufacture, or transport of marijuana.

- “Data on poverty, employment, and cannabis arrests.”

- Harris acknowledged “a lot of difficulty with the measurement,” and a need to determine the “level of data”: counties, municipalities, census tracts, or even city blocks. She cautioned that it became harder to “figure out all these overlapping characteristics at smaller units of analysis.” Harris went over basic racial demographic data and statistics identified in the definition, such as median income and employment.

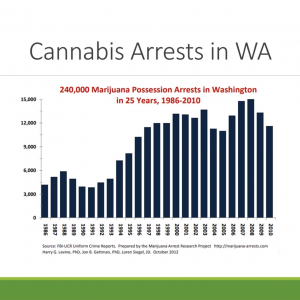

- Cadigan discussed cannabis enforcement, saying that after the federal Weed and Seed program in the early 1990s, Washington saw “exponential growth in arrests for possession of cannabis.” She indicated that King, Pierce, Snohomish, and Spokane counties had the highest “numbers of people” arrested, whereas the highest “ratios” of cannabis possession arrests relative to the population between 2001 and 2010 were in Whitman, Kittitas, and Benton counties.

- Arrests for possession of cannabis targeted African Americans disproportionately, Cadigan noted, “despite equivalent use of all races.” She said that hispanic populations were arrested at a higher rate as well, “but not to the extent that black individuals are.” Cadigan indicated that this disproportionality has persisted “post-legalization.”

- In 2019, Washington State University (WSU) researchers shared a presentation on post I-502 cannabis arrests in Washington, finding a 14% decrease in the disproportionality of African Americans arrested for cannabis possession between 2009 and 2015. However, the same data revealed a 127% increase in the proportion of African Americans arrested for cannabis sales. The WSU findings were similar to a 2018 report from UW researchers which also identified continuing racially disparate enforcement.

- Cadigan told the task force that she and Harris were attempting to pull “case level data” for cannabis conviction outcomes from the Washington State Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC), “and then we can put them in a geographic context.” Cadigan said she and Harris had already looked at poverty rates based on census tracts and planned to add layers for other factors in the disproportionate impact area definition.

- “Outline a few open areas of questions or issues.”

- Cadigan asked, “what kind of criteria do we overlay” to map disproportionate impacts, before openly wondering how the task force would measure “cumulative disadvantage.” She also felt rural areas “can be a little more difficult” as they often had larger census tracts.

- Cadigan said the next issue was income-based program usage because “individuals with drug convictions...aren’t eligible” for those federal programs. She felt that factor could “work against what we’re trying to accomplish here.”

- Harris spoke to a final question around “timing” of residency and how long someone lived in a disproportionately impacted area. She said “gentrification” made people “question what years of data are appropriate to look at” and noted “the large gap between existing and potential property values” that drew in “wealthier residents” had made Seattle “the third most quickly gentrifying city in the U.S.” Further complicating calculations, gentrification happened over different periods of time in different parts of the city.

- Harris said the operating principles for the task force could go a long way in defining who should be most helped by the program as well as forecasting “what does success look like” when the program was evaluated.

- Task force members and citizens had feedback and questions about how the group could further clarify the definition.

- Morgan commented that “in going forward with your research, I would love to see research on these counties” which may “look like they’re sleepy towns” but have highly disproportionate enforcement. “A sneaking one coming up on our heels is Snohomish County,” she claimed. Morgan encouraged Harris and Cadigan to review more data for that area and track the movement of communities of color due to gentrification (audio - 1m, video).

- Curtis King, representing Senate Republicans, wanted to ensure that he could get copies of the data researchers had already shown during their presentation. Task force staffer Christy Curwick-Hoff confirmed she would share the presentation with members (audio - 1m, video).

- Cherie MacLeod, representing the Association of Washington Cities (AWC), said the City of Seattle had lacked the capacity “to review thousands and thousands of cases,” and applauded Harris and Cadigan for their “amazing work.” Additionally, she agreed that gentrification had changed the makeup of Seattle and communities had been “displaced, disinvested.” MacLeod hoped gentrification could be accounted for to “allow people to participate” in the equity program (audio - 1m, video).

- Christopher Poulos, representing the Washington State Department of Commerce, wanted to know about WSLCB’s “vast exclusions” as cannabis convictions were literally counted against applicants during prior licensing application windows. He didn’t understand how that could “fit together” with a goal to not penalize applicants with cannabis convictions. Hoff responded that before the passage of HB 2870, which created both the social equity program and task force, WSLCB was given discretion to consider criminal records under RCW 69.50.331(1)(a). Poulos was grateful for the clarification, predicting “this won’t be the last time I speak on this” (audio - 4m, video).

- Raft Hollingsworth, representing cannabis producers, asked if there was information on the “outcomes of those restorative justice programs” in California. Cadigan replied that they had “very little data” on that as applicants were still “clogged up” so it was “a little too early to tell.” She said Los Angeles’ zip code-based system appeared to be “not working” to help disadvantaged groups “accessing the licenses.” Hollingsworth inquired about rural counties with small minority populations still experiencing disproportionate cannabis enforcement, and asked if that meant that African Americans were “six, seven, eight times” more likely to receive cannabis policing. Cadigan said disproportionality could change “within neighborhood even, even getting more granular.” Hollingsworth viewed the licenses as “a form of reparations” that should be going to people and communities “disproportionately impacted by the war on drugs” (audio - 4m, video).

- Aaron Barfield, member of Black Excellence in Cannabis (BEC), offered criticism of other social equity programs and said that “nobody is being held accountable” at WSLCB for earlier bias. He felt “that leads to us getting here over and over again” and asked for accountability to be one benchmark in judging the effectiveness of the program (audio - 1m, video).

- MacLeod asked about the “location of the conviction” versus the “residential address provided by the person who was convicted.” Cadigan said that state case records specified an individual’s “residential address that they provide the court” (audio - 1m, video).

- Rebecca Saldaña, representing Senate Democrats, was supportive of “more granular data” and careful consideration of what years to look at in judging disproportionately impacted areas. She also believed the data methodology could be adapted to reflect demographic migration to enhance the program’s effectiveness at achieving equity (audio - 2m, video).

- Monica Martinez, another representative of licensed producers, echoed Saldaña’s call for additional information, particularly on disproportionate arrests in rural counties, and asked for clarification on the state’s overall rates for cannabis arrests of African Americans compared to other racial groups (audio - 2m, video).

- A proposal was made to establish the first work group within the task force to focus on the definition of disproportionately impacted areas.

- Morgan advised creation of a work group. Hoff then proposed that the work group members develop a recommended definition for the entire task force to consider. “There’s a lot of tension,” she said, “between doing this work quickly” so WSLCB could begin rulemaking to structure the program, and designing criteria “thoughtfully and intentionally.” Hoff explained the work group would partner up with Harris and Cadigan to “refine these categories” (audio - 2m, video).

- David Mendoza, representing the Latinx community, supported establishing the new work group (audio - 1m, video).

- Co-Chair Paula Sardinas, representing the Washington State Commission on African American Affairs (CAAA), also backed creation of a new sub-group, provided “there’s equity on that other work group and that there’s minority representation” (audio - <1m, video).

- After a motion to establish the work group from WSLCB task force representative Ollie Garrett, seconded by Michelle Merriweather, a representative of the African American community, the task force members voted unanimously to create a data-focused work group. Hoff said the work group meetings would be open to the public and reaffirmed that “no decisions will be made at the work group,” rather, its members would “provide guidance” for consideration by the entire task force (audio - 3m, video).

Information Set

-

Presentation - Task Force Responsibilities (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Summary of Public Comments at WSLCB Social Equity Events (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Memorandum (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Task Force Bylaws - v0 (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Task Force Operating Principles - v0 (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Complete (6h 17m 26s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Welcome - Benjamin Danielson (3m 49s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Welcome - Christy Curwick Hoff (5m 10s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Approval of Agenda (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 04 - Introductions - Benjamin Danielson (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Introduction - David Mendoza (3m 11s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 06 - Introduction - Carmen Rivera (1m 57s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Introduction - Paula Sardinas (2m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Introduction - Tamara Berkley (1m 31s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 09 - Introduction - Pablo Gonzalez (2m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 10 - Introduction - Monica Martinez (2m 30s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 11 - Introduction - Raft Hollingsworth (4m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 12 - Introduction - Craig Bill (3m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Introduction - Michelle Merriweather (16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 14 - Introduction - Joe Solorio (1m 35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 15 - Introduction - Cherie MacLeod (3m 34s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 16 - Introduction - Yasmin Trudeau (2m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 17 - Introduction - Christopher Poulos (3m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 18 - Introduction - Ollie Garrett (3m 27s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 19 - Introduction - Melanie Morgan (2m 35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 20 - Introduction - Kelly Chambers (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 21 - Introduction - Curtis King (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Introduction - Rebecca Saldaña (5m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 23 - Introduction - Benjamin Danielson (1m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 24 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning (1m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 25 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning - Response - David Mendoza (3m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 26 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning - continued (2m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 27 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Christy Curwick Hoff (14m 45s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 28 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Melanie Morgan (2m 24s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (7m 36s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 30 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Curtis King (44s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 32 - General Public Comments (4m 52s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 33 - Comment - Paul Brice (8m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 34 - Comment - Gregory Foster (3m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 35 - Comment - Mike Asai (16m 44s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 36 - Comment - Kim Henley (5m 28s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 37 - Comment - Kim Henley - Response - Paula Sardinas (4m 58s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 38 - Comment - Aaron Barfield (3m 19s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 39 - Comment - Chris Marr (6m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 40 - Comment - Duane Dunn (5m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 41 - Comment - Zach Fairley (9m 47s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 42 - General Public Comments - Response - Pablo Gonzalez (6m 40s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 43 - Introduction - Michelle Merriweather (49s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 44 - Comment - Bria Jackson (2m 51s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 45 - General Public Comments - Response - Kelly Chambers (1m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 46 - General Public Comments - Response - Paula Sardinas (48s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 47 - Initial Break - Benjamin Danielson (2m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 48 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Christy Curwick Hoff (10m 8s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 49 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Ollie Garrett (4m 58s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 50 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Paula Sardinas (3m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 51 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Cherie MacLeod (1m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 52 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (2m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 53 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Peter Manning (4m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 54 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Melanie Morgan (2m 43s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 55 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Jferrich Oba (5m; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 56 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Mike Asai (5m 14s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 57 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Christy Curwick Hoff (13m 40s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 59 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 60 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Paula Sardinas (4m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 61 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Pablo Gonzalez (1m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 62 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Vote (9m 22s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 63 - Task Force Bylaws - Melanie Morgan (1m 55s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 64 - Task Force Bylaws - Christy Curwick Hoff (2m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 65 - Task Force Bylaws - Elise Rasmussen (8m 17s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 66 - Task Force Bylaws - Question - Reimbursement - Melanie Morgan (5m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 67 - Task Force Operating Principles - Paula Sardinas (35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 68 - Task Force Operating Principles - Elise Rasmussen (7m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 69 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Paula Sardinas (1m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 70 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Paul Brice (3m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 71 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Christopher Poulos (1m 32s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 72 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Pablo Gonzalez (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 74 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Monica Martinez (1m 27s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 75 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - David Mendoza (1m 17s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 76 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 77 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Raft Hollingsworth (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 78 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Monica Martinez - continued (1m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 79 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Yasmin Trudeau (1m 56s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 80 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Melanie Morgan (3m 19s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 81 - Afternoon Break - Melanie Morgan (1m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 82 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Melanie Morgan (57s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 83 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Alexes Harris and Michele Cadigan (23m 16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 84 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Melanie Morgan (1m 21s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 85 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Curtis King (34s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 86 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Cherie MacLeod (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 87 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Christopher Poulos (3m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 88 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Raft Hollingsworth (3m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 89 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Aaron Barfield (1m 16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 90 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Cherie MacLeod (46s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 91 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 36s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 92 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Monica Martinez (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 96 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Work Group Proposal - Vote (2m 45s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 97 - Reflections - Melanie Morgan (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 98 - Reflection - Pablo Gonzalez (1m 29s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 99 - Reflection - Monica Martinez (2m 15s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 100 - Reflection - Kelly Chambers (41s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 101 - Reflection - Paul Brice (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 102 - Reflection - Paula Sardinas (2m 51s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 103 - Reflection - David Mendoza (2m 39s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 104 - Reflection - Cherie MacLeod (3m 18s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 105 - Reflection - Rebecca Saldaña (3m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 106 - Reflection - Paul Brice - continued (1m 26s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 107 - Wrapping Up - Paula Sardinas (11s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 108 - Wrapping Up - Melanie Morgan (6m 56s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

-

WA SECTF - Public Meeting - General Information

[ InfoSet ]

-

Bylaws - v1 (Feb 4, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Operating Principles (Feb 4, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Conversation Norms - v2 (Feb 16, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Recommendations - 2021 (Jan 18, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Recommendations - 2021 - Response - WSLCB (Jan 14, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v1 (Oct 24, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v2 (Dec 6, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v3 (Dec 8, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - Statement - WSLCB - v1 (Nov 17, 2022) [ Info ]

-

-

Minutes - v0 (Dec 9, 2020) [ Info ]