Review of the task force’s scope and responsibilities, draft bylaws, and operating principles elicited member perspectives on the kinds of systemic racism they would attempt to address within the state’s legal cannabis market.

- Lead staffer Christy Curwick Hoff briefed on the group’s scope and responsibilities as defined in statute, followed by remarks from some of the legislators on the task force.

- Hoff began with the law creating the task force, HB 2870, “just to make sure we’re all on the same page of what the scope of this task force is, and what the specific…responsibilities outlined for us are as task force members and also as community members” (audio - 15m, video, presentation).

- Hoff reviewed each section of HB 2870 starting with the lawmakers’ intent which she said “grounded” the task force in the Legislature’s goals. She read part of the intent, calling attention to making the state’s cannabis industry “equitable and accessible to those most adversely impacted by the enforcement of drug-related laws, including cannabis-related laws” with emphasis on “promoting business ownership among individuals who have resided in areas of high poverty and high enforcement of cannabis-related laws.” However, lawmakers indicated task force action was “not to result in an increase in the number of cannabis retailer licenses” absent separate “legislative action.”

- In the session law, the latter provision is spelled out as, “It is the intent of the legislature that implementation of the social equity program authorized by this act not result in an increase in the number of marijuana retailer licenses above the limit on the number of marijuana retailer licenses in the state established by the board before January 1, 2020.”

- This would seem to contravene the authority vested in the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) by the legislature in RCW 69.50.354, which states, “There may be licensed, in no greater number in each of the counties of the state than as the state liquor and cannabis board shall deem advisable, retail outlets established for the purpose of making marijuana concentrates, useable marijuana, and marijuana-infused products available for sale to adults aged twenty-one and over.”

- Hoff said section two “creates the social equity program” at the WSLCB from “retail licenses that have been forfeited, revoked, or cancelled, or that have not been issued without exceeding the limit on the current licenses” allowed in a jurisdiction. At the time, she said that “was about 35 licenses.”

- WSLCB Board Member Ollie Garrett, the agency’s representative on the task force, confirmed the available license count but pointed out that “quite a few of them are in ban and moratorium” areas.

- Washington State Commission on African American Affairs (CAAA) Commissioner Paula Sardinas, who would be voted Co-Chair of the task force later in the meeting, called attention to the law’s allowance for “any other licenses that have been revoked” and asked if “from the date the act went into law, which I believe was June 12th, til today, if there are any additional licenses subject to revocation that should be included.” Hoff confirmed.

- At publication time, one additional retail license had become available raising the total to 35.

- Hoff said that prospective licensees had to qualify as “social equity applicants” who had resided “for at least five of the preceding ten years in a disproportionately impacted area, or an individual who has been convicted of a cannabis-related offense, or a family member of someone who has been convicted of a cannabis offense.” The law also contained “a framework” for what constituted a disproportionately impacted area including poverty and unemployment rates; high rates of “income-based federal or state programs”; or “arrests, conviction, or incarceration related to cannabis offenses.” Hoff commented that disproportionately impacted areas could “be further defined, and should be further defined by this task force.” Applicants would be expected to “submit a social equity plan” which would be “used by LCB to prioritize which applicants will receive a license” as well as by the Washington State Department of Commerce in deciding who would receive technical assistance grants. The task force was asked to define what social equity plans should include to receive increased prioritization.

- Hoff then explained that section three dealt with the “social equity technical assistance grant program” administered by Commerce. She said this was the reason that Christopher Poulos, Executive Director of the Washington Statewide Reentry Council, was representing the department on the task force. Section four addressed the annual appropriation of “$1.1 million for that grant program.”

- The task force itself was defined in section five, with Hoff stating WSLCB had a “timeline that the social equity program is in existence from December one of [2020] through July 1st, 2028.” She acknowledged the late start of the task force due to the coronavirus pandemic, and suggested one topic for consideration was “whether that timeline should be extended because of the delay.”

- The task force’s function was to “make recommendations to LCB including but not limited to establishing a social equity program for existing retail licenses,” and to “make additional recommendations to LCB, beyond the social equity program” to increase equity in the industry “more broadly.” Moreover, the task force would “advise the governor and the legislature on policies related to the social equity program, and that is very broad language” Hoff observed, clarifying that further recommendations could require executive or legislative approval.

- Hoff called attention to the 18 members on the task force and how state agencies, licensees, and community groups had been included “as appointed by the legislature.” Task force members could invite “advisory participants” who would have “the ability to inform and provide guidance” to the group. She mentioned that task force staffing would come from the Washington State Governor's Interagency Council on Health Disparities but the state’s Office of Equity would “take on that responsibility” once they were funded.

- Hoff was “the only dedicated staff” for the task force, but Elise Rasmussen, Project Manager for the “just finished” Washington State Environmental Justice Task Force would support the task force through the end of 2020 “to help us get started.” Judy Edwards, a WSLCB Administrative Assistant, would dedicate “20% of her time to support this task force” with technical and “administrative tasks...for the next four to six months.”

- Hoff brought up the statutory timeline of December 1st for the task force’s report to the legislature envisioned in HB 2870, stating that “due to the delay in getting us started we’ll need to determine a more feasible timeline” in a future meeting.

- In section six, Hoffman indicated that WSLCB had been given authority “to issue these social equity licenses.” The final section was “standard null and void language regarding if appropriations are not in the budget.”

- Hoff offered a plan from staff that prioritized “the guidance that the task force is supposed to be providing to LCB to develop” the program since the agency “and the community” were waiting on progress. “And then after that we can take on some of the other questions and priorities that the task force is interested in,” she concluded. Hoff said required guidance included “factors that LCB must consider in distributing the licenses” and whether “any additional licenses should be issued.”

- Lastly Hoff reminded members that the task force was only authorized through June 2022, “unless, of course, the legislature decides to extend that.”

- See Cannabis Observer’s coverage of the law’s House policy committee public hearing and executive session; the House fiscal committee public hearing and executive session; and the House session when the chamber passed the bill. We also covered the legislation’s Senate policy committee public hearing and executive session, and observed the Senate session which resulted in a final bill rewrite before it was signed into law on March 31st.

- Hoff reviewed each section of HB 2870 starting with the lawmakers’ intent which she said “grounded” the task force in the Legislature’s goals. She read part of the intent, calling attention to making the state’s cannabis industry “equitable and accessible to those most adversely impacted by the enforcement of drug-related laws, including cannabis-related laws” with emphasis on “promoting business ownership among individuals who have resided in areas of high poverty and high enforcement of cannabis-related laws.” However, lawmakers indicated task force action was “not to result in an increase in the number of cannabis retailer licenses” absent separate “legislative action.”

- Hoff then provided “an opportunity for our legislators to offer any guidance to us...since this came from their mandate.”

- Representative Melanie Morgan, who would later be voted task force Co-Chair along with Sardinas, stated she had pushed for HB 2870 with the help of the CAAA, Black Excellence in Cannabis (BEC), and others. There were “things we need to push the envelope on” when making recommendations “and I’m willing to go there.” Morgan said issuing licenses was her primary focus, and that she was at the meeting “to start that process, ASAP...to bring the balance to the Black/African American community.” She felt that “as soon as we get everybody in an equitable position, now we can start looking at this as an overall social equity for every culture.” Morgan encouraged “innovative” ideas on the “direction” of the program if there was agreement they helped the marginalized communities represented by the task force (audio - 2m, video).

- Senator Rebecca Saldaña found WSLCB was “set up as an enforcement and compliance, not a coach or business support” institution, and felt its structure was “racist and biased” just like “all of our drug laws” (audio - 8m, video).

- Without attributing discrimination to individual employees, Saldaña felt “the agency itself and the way it’s structured is one that will continue to get in the way because of how it was first formed.” Saldaña credited the increased racial diversity of state lawmakers as one of the driving factors in passing HB 2870. Skepticism about the WSLCB motivated her to see that the Council on Health Disparities staffed the task force rather than the agency.

- According to the Washington State Secretary of State (WA SOS) page on African Americans in the Washington State Legislature, only one African American woman, Rosa Franklin, had previously served in the state senate. At publication time, candidate T’wina Nobles was leading in the 28th District senate election. Crosscut noted, “Nine Black women are campaigning for state legislative seats this year — far more than Franklin remembers ever running before in a single year. A 10th candidate, who is gender nonbinary and identifies as Black femme, is running as well.”

- Saldaña described her district as having Washington’s largest African American population “despite gentrification and displacement” and wanted to see newly licensed retail shops “add value to their community.” She thanked BEC for their engagement.

- Saldaña wanted more funding and staffing to support the task force than had been provided, but COVID-19 meant “we are in this context of the triple pandemics that are facing our communities.” Saldaña regretted that “we have been delayed” but assured everyone she would listen to impacted communities and see the task force “adequately staffed and resourced” as well as being a “partner” for “any legislation that needs to happen.”

- Without attributing discrimination to individual employees, Saldaña felt “the agency itself and the way it’s structured is one that will continue to get in the way because of how it was first formed.” Saldaña credited the increased racial diversity of state lawmakers as one of the driving factors in passing HB 2870. Skepticism about the WSLCB motivated her to see that the Council on Health Disparities staffed the task force rather than the agency.

- Republican members, Senator Curtis King (audio - 1m, video) and Representative Kelly Chambers (audio - <1m, video) offered no additional comments on the task force’s scope or responsibilities.

- Hoff began with the law creating the task force, HB 2870, “just to make sure we’re all on the same page of what the scope of this task force is, and what the specific…responsibilities outlined for us are as task force members and also as community members” (audio - 15m, video, presentation).

- Task Force Co-Chair Melanie Morgan and staff discussed the group’s draft bylaws.

- Morgan began the discussion, commenting that even if the bylaws weren’t formally adopted by the task force at that time “we do want to have a robust discussion” after which staff would revise them for eventual adoption (audio - 2m, video).

- Hoff told task force members that bylaws and operating procedures were “foundational documents” for groups like theirs and “regularly” used by staff “to make sure we know how we’re going to work.” She said the draft bylaws, derived from documents that guide the health disparities council, “describe how the task force operates and makes decisions.” In working for that council, Hoff believed they had “used our bylaws and operating principles in a way... that promote equity and social justice.” She offered “to adapt them as they made sense for this task force” (audio - 2m, video).

- Rasmussen went over the draft bylaws (audio - 8m, video):

- Article I: Membership - followed the language in HB 2870.

- Article II: Officers & Workgroups - As the group had already opted to elect Morgan and Sardinas Co-Chairs, “we’ll make sure that that language is included.” Their main function would be to “represent the task force in official capacities” and the term of office would be “as long as this task force is meeting.” The task force could also elect to establish work groups, explained Rasmussen.

- Article III: Meetings - “The task force will meet as often as necessary,” Rasmussen said, with only virtual meetings planned at the moment “due to Covid.” All the task force’s meetings were open to the public and “any decisions that the task force makes has to be done in an open, public meeting” allowing community members to “weigh in.” Meeting agendas would be “posted prior to task force meetings” and meeting minutes available “prior to the next meeting,” she said.

- Rasumussed explained that the draft included a clause around Meetings Interrupted by a Person or Group of People because “We have had, in the past, some experiences with people who are joining our meetings with no, sort of, intention to add to the conversation but rather to detract from it.” She believed it made sense to have a procedure to remove “blatantly offensive” participants from the hosting platform.

- Article IV: Meeting Procedures - Rasmussen went through rules for meeting quorum, order of business, public comment, motions and resolutions, manner of voting, and general rules of procedure, being “determined by these bylaws, the Administrative Procedures Act, the Open Public Meetings Act, and the Task Force’s authorizing authority, Engrossed, Second Substitute House Bill 2870.”

- Article V: Amendments - would allow the bylaws to be amended “if anything comes up later on,” she noted.

- Article VI: Construction of Rules - required the task force to “interpret the rules and procedures in these bylaws in a manner that best aligns with the intents of” HB 2870.

- Morgan opened the call to discussion, and asked about reimbursement for meals during virtual events (audio - 5m, video).

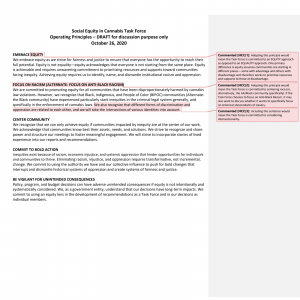

- During a discussion on the task force’s operating principles, many task force members offered their perspectives on how the organization should understand its scope and approach its responsibilities.

- Sardinas described the task force operating principles as “what it is the task force stands for and what we’re about” (audio - 1m, video). Hoff considered the operating principles a description of “the values that the task force agrees to as a group.”

- Rasmussen reviewed the draft operating principles and asked for “community input” on “what’s confusing, what questions do you have, what things would you like to change or add” (audio - 7m, video).

- Embrace Equity - We embrace equity as we strive for fairness and justice to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential. Equity is not equality—equity acknowledges that everyone is not starting from the same place. Equity is achievable and requires unwavering commitment to prioritizing resources and supports toward communities facing inequity. Achieving equity requires us to identify, name, and dismantle institutional racism and oppression.

- Rasmussen highlighted this principle would commit the task force to an equity-based approach instead of an equality-based approach, the difference being “equity assumes that communities are starting in different places.”

- Focus on Racism - We are committed to promoting equity for all communities that have been disproportionately harmed by cannabis law violations. However, we recognize that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities (Alternate: the Black community) have experienced particularly stark inequities in the criminal legal system generally, and specifically in the enforcement of cannabis laws. We also recognize that different forms of discrimination and oppression are related to each other, and we will take the intersections of various identities into account.

- Rasmussen said that “an alternate proposal that staff has” was to “focus on ‘anti-Black racism’ specifically” and potentially further emphasize “American-descendents of slavery, so a group within the black community.” Additionally, the language would commit the group to “considering intersectionality in its decision making processes.”

- Center Community - We recognize that we can only achieve equity if communities impacted by inequity are at the center of our work. We acknowledge that communities know best their assets, needs, and solutions. We strive to recognize and share power and structure our meetings to foster meaningful engagement. We will strive to incorporate stories of lived experience into our reports and recommendations.

- Commit to Bold Action - Inequities exist because of racism, economic injustice, and systemic oppression that hinder opportunities for individuals and communities to thrive. Eliminating racism, injustice, and oppression requires transformative, not incremental, change. We commit to using the authority we have and our collective influence to push for bold changes that interrupt and dismantle historical systems of oppression and create systems of fairness and justice.

- Be Vigilant for Unintended Consequences - Policy, program, and budget decisions can have adverse unintended consequences if equity is not intentionally and systematically considered. We, as a government entity, understand that our decisions have long-term impacts. We commit to using an equity lens in the development of recommendations as a Task Force and in our decisions as individual members.

- Embrace Equity - We embrace equity as we strive for fairness and justice to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential. Equity is not equality—equity acknowledges that everyone is not starting from the same place. Equity is achievable and requires unwavering commitment to prioritizing resources and supports toward communities facing inequity. Achieving equity requires us to identify, name, and dismantle institutional racism and oppression.

- Sardinas was supportive of the ‘anti-Black racism’ wording change in the Focus on Racism principle, as well as the “particular disproportionate impact” experienced by descendants of slavery (audio - 1m, video).

- Poulos asked that "people or individuals impacted by cannabis law violation" be included along with language around centering on communities (audio - 2m, video).

- Pablo Gonzalez disagreed with emphasizing ‘anti-Black racism’ and wanted to include “all types of people that have been socially discriminated against” such as “women as a whole, Hispanics as a whole” (audio - 2m, video).

- Michelle Merriwether supported adding both ‘anti-Black racism’ and wording about descendents of slavery (audio - 1m, video).

- Monica Martinez proposed the possibility of "all minorities and women" being the frame for task force discussions and asked for “more information” around which groups were “disproportionately marginalized” due to cannabis policing. “I would just hate to see us exclude other minorities who have also seen barriers,” she stated (audio - 1m, video; audio - 2m, video).

- David Mendoza advised moving away from “an either/or” consideration of particular subjects of racism in favor of “a both/and on this.” He suggested “we can include in the paragraph below...an emphasis on anti-Black racism” (audio - 1m, video).

- Saldaña understood the motivation to specify ‘anti-Black racism’ while also mentioning the impact of excessive cannabis law enforcement against immigrant communities, who could not only be barred from a cannabis license but “forcibly removed from our communities” and even deported (audio - 2m, video).

- Raft Hollingsworth was in agreement on using ‘anti-Black racism’ as it was a more prominent factor in the drug war but he didn’t believe women “were a target” to the same level as the African American community. He believed the language had value as it pertained to “restorative justice” (audio - 1m, video).

- Yasmin Trudeau spoke up to say that “intersectionality in community” could be recognized by “honoring the folks who brought forward this issue, honoring the community that brought forward this issue.” She supported using the term ‘anti-Black racism’ and “didn’t see any exclusion” resulting from it. To the contrary “being overly inclusive can sometimes result in not centering and honoring the folks that really need to be at the heart of the discussion” (audio - 2m, video).

- Morgan provided final comments on the operating principles: “the people that were impacted were the indigenous native and then black Africans that were brought here into slavery… that is not to say that we discount any other type of racism that is happening.” She wondered if the language of “anti-Black racism and racism” would be preferable. Morgan then asserted that the acronym BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of color) used in the draft language was "just another name that is being put on us." She noted that African American democrats in Tacoma “pushed back against that, and we wrote a resolution” opposing the term. Moreover, she felt the acronym led to “forgetting the word that we introduced in the first paragraph, which is ‘equity’” (audio - 3m, video).

- Given the diversity of views on the Focus on Racism principle, a vote on adopting the document was not contemplated and task force staff committed to revise the language for consideration at the task force’s next meeting. At publication time, subsequent meeting dates had not been declared on the task force website.

Information Set

-

Presentation - Task Force Responsibilities (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Summary of Public Comments at WSLCB Social Equity Events (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Memorandum (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Task Force Bylaws - v0 (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Task Force Operating Principles - v0 (Oct 22, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Complete (6h 17m 26s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Welcome - Benjamin Danielson (3m 49s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Welcome - Christy Curwick Hoff (5m 10s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Approval of Agenda (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 04 - Introductions - Benjamin Danielson (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Introduction - David Mendoza (3m 11s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 06 - Introduction - Carmen Rivera (1m 57s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Introduction - Paula Sardinas (2m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Introduction - Tamara Berkley (1m 31s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 09 - Introduction - Pablo Gonzalez (2m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 10 - Introduction - Monica Martinez (2m 30s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 11 - Introduction - Raft Hollingsworth (4m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 12 - Introduction - Craig Bill (3m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Introduction - Michelle Merriweather (16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 14 - Introduction - Joe Solorio (1m 35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 15 - Introduction - Cherie MacLeod (3m 34s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 16 - Introduction - Yasmin Trudeau (2m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 17 - Introduction - Christopher Poulos (3m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 18 - Introduction - Ollie Garrett (3m 27s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 19 - Introduction - Melanie Morgan (2m 35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 20 - Introduction - Kelly Chambers (1m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 21 - Introduction - Curtis King (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Introduction - Rebecca Saldaña (5m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 23 - Introduction - Benjamin Danielson (1m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 24 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning (1m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 25 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning - Response - David Mendoza (3m 5s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 26 - Introductions - Comment - Peter Manning - continued (2m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 27 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Christy Curwick Hoff (14m 45s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 28 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Melanie Morgan (2m 24s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (7m 36s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 30 - Task Force Scope and Responsibilities - Comment - Curtis King (44s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 32 - General Public Comments (4m 52s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 33 - Comment - Paul Brice (8m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 34 - Comment - Gregory Foster (3m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 35 - Comment - Mike Asai (16m 44s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 36 - Comment - Kim Henley (5m 28s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 37 - Comment - Kim Henley - Response - Paula Sardinas (4m 58s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 38 - Comment - Aaron Barfield (3m 19s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 39 - Comment - Chris Marr (6m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 40 - Comment - Duane Dunn (5m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 41 - Comment - Zach Fairley (9m 47s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 42 - General Public Comments - Response - Pablo Gonzalez (6m 40s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 43 - Introduction - Michelle Merriweather (49s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 44 - Comment - Bria Jackson (2m 51s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 45 - General Public Comments - Response - Kelly Chambers (1m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 46 - General Public Comments - Response - Paula Sardinas (48s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 47 - Initial Break - Benjamin Danielson (2m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 48 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Christy Curwick Hoff (10m 8s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 49 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Ollie Garrett (4m 58s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 50 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Paula Sardinas (3m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 51 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Cherie MacLeod (1m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 52 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (2m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 53 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Peter Manning (4m 13s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 54 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Melanie Morgan (2m 43s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 55 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Jferrich Oba (5m; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 56 - WSLCB Social Equity Engagement - Comment - Mike Asai (5m 14s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 57 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Christy Curwick Hoff (13m 40s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 59 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 33s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 60 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Paula Sardinas (4m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 61 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Presentation - Pablo Gonzalez (1m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 62 - Election of Task Force Co-Chairs - Vote (9m 22s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 63 - Task Force Bylaws - Melanie Morgan (1m 55s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 64 - Task Force Bylaws - Christy Curwick Hoff (2m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 65 - Task Force Bylaws - Elise Rasmussen (8m 17s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 66 - Task Force Bylaws - Question - Reimbursement - Melanie Morgan (5m 9s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 67 - Task Force Operating Principles - Paula Sardinas (35s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 68 - Task Force Operating Principles - Elise Rasmussen (7m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 69 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Paula Sardinas (1m 4s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 70 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Paul Brice (3m 12s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 71 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Christopher Poulos (1m 32s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 72 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Pablo Gonzalez (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 74 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Monica Martinez (1m 27s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 75 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - David Mendoza (1m 17s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 76 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 54s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 77 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Raft Hollingsworth (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 78 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Monica Martinez - continued (1m 59s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 79 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Yasmin Trudeau (1m 56s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 80 - Task Force Operating Principles - Comment - Melanie Morgan (3m 19s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 81 - Afternoon Break - Melanie Morgan (1m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 82 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Melanie Morgan (57s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 83 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Alexes Harris and Michele Cadigan (23m 16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 84 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Melanie Morgan (1m 21s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 85 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Curtis King (34s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 86 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Cherie MacLeod (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 87 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Christopher Poulos (3m 53s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 88 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Raft Hollingsworth (3m 42s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 89 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Aaron Barfield (1m 16s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 90 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Question - Cherie MacLeod (46s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 91 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Rebecca Saldaña (1m 36s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 92 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Comment - Monica Martinez (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 96 - Disproportionately Impacted Areas - Work Group Proposal - Vote (2m 45s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 97 - Reflections - Melanie Morgan (1m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 98 - Reflection - Pablo Gonzalez (1m 29s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 99 - Reflection - Monica Martinez (2m 15s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 100 - Reflection - Kelly Chambers (41s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 101 - Reflection - Paul Brice (2m 3s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 102 - Reflection - Paula Sardinas (2m 51s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 103 - Reflection - David Mendoza (2m 39s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 104 - Reflection - Cherie MacLeod (3m 18s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 105 - Reflection - Rebecca Saldaña (3m 20s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 106 - Reflection - Paul Brice - continued (1m 26s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 107 - Wrapping Up - Paula Sardinas (11s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 108 - Wrapping Up - Melanie Morgan (6m 56s; Oct 28, 2020) [ Info ]

-

-

WA SECTF - Public Meeting - General Information

[ InfoSet ]

-

Bylaws - v1 (Feb 4, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Operating Principles (Feb 4, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Conversation Norms - v2 (Feb 16, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Recommendations - 2021 (Jan 18, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Recommendations - 2021 - Response - WSLCB (Jan 14, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v1 (Oct 24, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v2 (Dec 6, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - v3 (Dec 8, 2022) [ Info ]

-

Legislative Report - Statement - WSLCB - v1 (Nov 17, 2022) [ Info ]

-

-

Minutes - v0 (Dec 9, 2020) [ Info ]