Director of Policy and External Affairs Justin Nordhorn discussed the background, intent, and changes requested in draft legislation on “psychotropic” and “impairing” cannabis compounds.

Here are some observations from the Monday September 27th Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) webinar on the “regulation of cannabinoids” legislative proposal.

My top 3 takeaways:

- Nordhorn offered background as to why agency leaders drafted request legislation seeking greater authority around “psychotropic compounds” in cannabis (audio - 13m, video).

- Nordhorn said his goal was to “make sure that people have an understanding of what the language is, how it was drafted, what our intent is” before fielding questions or remarks on the proposal. He promised to share “why we’re doing this and what we believe the legislative impacts are” to set a “foundation” for people to offer feedback. Nordhorn reported that the request was drafted throughout 2021 as there were “a number of issues at the beginning of the year” that involved “variable impairing cannabinoids, the most prevalent at the time was delta-8[-tetrahydrocannabinol]” (THC).

- After significant public outcry “from licensees, industry members, prevention/public health,” he stated, staff developed a “three prong approach”:

- Established policy and interpretive statements

- Opened a rulemaking project on THC regulations

- Prepared agency request legislation

- Agency staff had arranged two deliberative dialogues with subject matter experts on cannabis plant chemistry on June 3rd and July 20th, Nordhorn remarked, with the former event being a catalyst to refile the rulemaking project on July 7th so that “the scope of the rulemaking could be expanded.” Additionally, WSLCB officials hosted a listen and learn forum about the rulemaking project on September 9th. He said, “this process is kind of going alongside of that...this isn’t something that’s easy to put together in a couple weeks.” The draft legislation wasn’t “necessarily a final product moving forward,” Nordhorn explained, and staff would be “deliberative and diligent” in developing the proposal.

- Nordhorn described themes he believed had emerged in public comments:

- An “across the board” consensus that “delta-8 and other impairing cannabinoids should be regulated in some form or another”

- “Artificial or fake cannabinoids such as your K2 and Spice...should not be in the marketplace...we wanted to take that and move that forward”

- “According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), they’ve seen 660 cases of exposures to delta-8-THC that were reported to the poison control centers, January to July of this year,” and “39% of the cases” involved someone under the age of 18. FDA data noted cases included hospitalization and complaints from consumers, law enforcement, and “animal poisonings.”

- On June 29th, staff reported that they’d reached out to the Washington Poison Center (WAPC), Washington State Department of Health (DOH), and Washington State Board of Health (SBOH) and found “there haven’t been any adverse events reported” in the state. Reached for comment in late June, the Washington Poison Center (WAPC) confirmed adding a code for delta-8-THC in March but had not documented any cases involving the compound at that time.

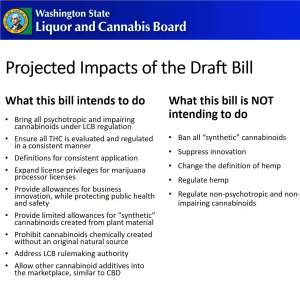

- The draft request bill would address stakeholder concerns, Nordhorn relayed, while steering clear of “the non-psychotropic area.” Agency leaders sought to regulate potentially impairing cannabis compounds in order to safeguard public health and safety, he told attendees, and wanted any law to be responsive to “not only the current state of...Delta-8 and Delta-10[-THC]” but also “if something else comes up.” Nordhorn said clear definitions would be important “for common terms, that way folks aren’t using them in different ways across different areas,” indicating there was already “misinterpretation” in “how we’re using the language right now.” Moreover, regulators wanted licensees to have the chance to “use the non-psychotropic cannabinoids beyond [cannabidiol] CBD,” like cannabigerol (CBG) and cannabinol (CBN), as additives in cannabis products, he said. Nordhorn’s view of the proposal was that it would “bring in the psychotropic and impairing cannabinoids” under WSLCB authority and allow them to be included in products sold in the legal cannabis market. THC would be “evaluated and regulated in a consistent manner,” he explained.

- Nordhorn mentioned the bill would “expand license privileges for the processors” and “provide allowances for business innovations while protecting public health and safety.” To accomplish this, he commented that there would be:

- “Limited allowances for synthetic cannabinoids created from plant material”

- A prohibition on ‘artificial cannabinoids’ “chemically created...without any natural source”

- Sufficient “regulatory authority to create the rules so that we can be flexible and responsive.”

- “Allowing some of the non-psychotropic additives to be able to come into [the] market similar to CBD.”

- Nordhorn then insisted the draft bill would not:

- “Ban all synthetic cannabinoids”

- “We’re not trying to suppress innovation”

- “We’re not trying to change anything on the hemp side of the equation” except when the “THC level...crosses the 0.3% threshold”

- “Not intending to regulate non-psychotropic and non-impairing cannabinoids”

- Citing the June 3rd deliberative dialogue conversation on phytocannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and artificial cannabinoids, Nordhorn said the first two categories had “crossover,” containing both natural and synthetic cannabinoids. For this reason, WSLCB staff were trying to have allowances for their use in legal products while “wholly” prohibiting use of artificial cannabinoids. He reported that existing law “basically is saying no synthetics, at all” and would need clarification if they were to be permitted.

- Nordhorn went over the specifics of the draft request bill, describing new and revised definitions and licensee privileges (audio - 17m, video).

- Nordhorn said the bill would add the following definitions:

- “(ss) ‘Plant Cannabis’ means all plants of the general[sic] Cannabis, including marijuana as defined in subsection (ff) of this section, and hemp as defined in RCW 15.140.020.”

- “(e) ‘Cannabinoid’ means any of the chemical compounds that are the active constituents of the plant Cannabis including, but not limited to, tetrahydrocannabinol, tetrahydrocanabinolic acid, cannabidiol, cannabidiolic acid, cannabinol, cannabigeral, cannabichromence, cannabicyclol, cannabivarin, tetrahydrocannabivarin, cannabidivarin, cannabichromevarin, cannabigerovarin, cannabigerol monomethyl ether, cannabielsoin, and cannabicitran. Cannabinoids do not include artificial cannabinoids, as that term is defined in this section and in Schedules I through V of the Washington state controlled substances act.”

- According to Nordhorn, the purpose here was drawing attention to “the compounds that are active constituents of plant cannabis” and intended to provide both “consistency and additional flexibility as other compounds are identified.” This was also an effort to be proactive in the event the legislature “decides to change the term ‘marijuana’ to ‘cannabis’...we can then differentiate cannabis” from “plant Cannabis,” he remarked.

- “(c) ’Artificial cannabinoid’ means a chemical substance that is created or manufactured by a chemical reaction that is structurally the same or substantially similar to the molecular structure of any chemical substance derived from the plant Cannabis that is a cannabinoid receptor agonist and includes, but is not limited to, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation that is not listed as a controlled substance in Schedules I through V of the Washington state controlled substances act. Artificially derived cannabinoids do not include:

- (1) A naturally occurring chemical substance that is separated from the plant Cannabis by a chemical or mechanical extraction process;

- (2) Cannabinoids that are produced by decarboxylation from a naturally occurring cannabinoid acid without the use of a chemical catalyst; or

- (3) Any other chemical substance identified by the board in consultation with the department[of health], by rule.”

- Nordhorn stated artificial cannabinoids were not derived from a “growing plant” whereas synthetic cannabinoids created by chemically altering plant extracts “are not fitting into” the definition.

- “(ccc) ‘Synthetically derived cannabinoid’ means any cannabinoid that is created by a chemical reaction that changes the molecular structure of any natural cannabinoid derived from the plant Cannabis to another cannabinoid found naturally in the plant Cannabis”

- If the chemical reaction was “originating from that natural plant” and not “strictly from the lab,” he said it might be permitted.

- “(ddd)(1) ‘Tetrahydrocannabinol’ or ‘THC’ includes all tetrahydrocannabinols that are artificially, synthetically, or naturally derived, including but not limited to delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol, delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol, and the optical isomers of delta-8 or delta-9 cannabinol, and any artificially or synthetically derived cannabinoid that is reasonably determined to have an intoxicating or psychotropic impairing effect.

- (2) Notwithstanding (1) of this subsection, tetrahydrocannabinol includes concentrated resins or cannabinoids, and the products thereof, produced from the plant Cannabis, whether or not the cannabinoids were derived from a marijuana plant containing a THC concentration greater than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

- “We intend to establish that all THC cannabinoids fall under the scope of the definition...regardless of its origin,” said Nordhorn, though it didn’t “remove the 0.3% threshold” to be included.

- “(fff) ‘Total THC’ means the sum of the percentage, by weight or volume measurement of tetrahydrocannabinolic acid multiplied by 0.877, plus, the percentage by weight or volume measurement of tetrahydrocannabinol.”

- Regardless of cannabinoid type, all “would contribute toward the Total THC,” he commented, which should help with questions about “serving sizes” for products without delineating between cannabinoids.

- “(f) ‘Catalyst’ means a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without itself undergoing any permanent chemical change.”

- Nordhorn said staff had learned how “catalysts are used in the synthesis process” and that the aim was to clarify this was “a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without undergoing any permanent change itself.”

- “(w) ‘Extract’ means a solid, viscid, or liquid substance extracted from a plant, or the like, containing its essence in concentrated or isolated form” and “(x) ‘Extraction’ means the process to separate or obtain a solid, viscid, or liquid substance from a plant or parts of a plant, by pressure, distillation, treatment with solvents, or the like.”

- Extraction was the process which resulted in an extract, which contained the plant “in a concentrated or isolated form” and involved solvents, Nordhorn conveyed, which differed from catalysts.

- “(q) ‘Distillate’ means to extract from the plant Cannabis where a segment of one or more cannabinoids from an initial extraction are selectively concentrated through a mechanical or chemical process, or both, with all impurities removed” and “(aa) ‘Isolate’ means extract from the plant Cannabis of 95 percent or more of a single cannabinoid compound.”

- Nordhorn reported that the intent was to distinguish between the initial extraction distillates that had been “selectively concentrated through...the extraction process...removing the impurities” and isolates that focus on “a single cannabinoid.”

- Nordhorn then described how proposed legislation would amend existing definitions:

- ‘CBD product’ would exclude items which “have any psychotropic cannabinoids contained in the product.”

- ‘Marijuana’ or ‘marihuana’ would be modified to reference the plant Cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol, and be inclusive of “concentrated resins, cannabinoids, and the products thereof.” An exception for hemp would be amended to say “unless the tetrahydrocannabinol concentration is greater than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

- ‘Marijuana processors’ would be redefined to allow license holders to “compound, convert, process, and prepare, either directly or indirectly or by extraction from the plant Cannabis as defined in subsection (ss) of this section, of natural origin, grown by a licensed producer, unless sourced and used as an additive in accordance with RCW 69.50.326.”

- License privileges in RCW 69.50.325 defined processors as able to “process, package, and label” cannabis items, and the new allowances were intended to permit “some of the innovation that is coming through the marketplace.” As CBD was the only additive cited in RCW 69.50.326 and didn’t allow for “inclusion of some of the others,” staff wanted to permit more flexibility “for non-psychotropic cannabinoids.”

- HB 2334 (“Regulating the use of cannabinoid additives in marijuana products”) was the enacting law for the use of imported CBD as an additive, mandating a WSLCB rulemaking project for implementation.

- ‘Marijuana Concentrates’ would make reference to examples including “kief, live resin, rosin, hash, or bubble hash” with 10% or more “total THC.”

- ‘Marijuana-infused products’ would include a mention of “isolates, or distillates” having 10% or more “total THC.”

- ‘Marijuana producer’ would mean those licensed to produce, “prepare, and propagate marijuana directly from a natural origin.”

- As CBD was the only additive cited in RCW 69.50.326 and didn’t allow for “inclusion of some of the others,” staff sought to enable import of “other nonpsychotropic cannabinoids, or a nonpsychotropic plant Cannabis isolate.” In addition to passing pesticide and heavy metals tests, two new requirements would be placed on imported cannabinoids:

- “(c) Is accompanied by a disclosure statement describing production methods including, but not limited to, solvent use, catalyst use, and synthesis or conversion methods; and

- (d) Is only added to a product authorized for production, processing, or sale under this chapter, and is not further processed or converted into a psychotropic impairing substance.”

- The statute would be amended to require cannabis testing to feature “other nonpsychotropic cannabinoid[s]” while adding two subsections:

- (4) Licensed marijuana producers and licensed marijuana processors may not use any artificial cannabinoids, as defined in this chapter, as an additive to any product authorized for production, processing, and sale under this chapter.

- (5) The board must revise rules as appropriate to conform to the terminology described in this act.”

- Nordhorn concluded by noting that RCW 69.50.342 would be changed to ensure the Board’s authority included “(o) The production, processing, transportation, delivery, sale, and purchase of naturally, or synthetically derived, cannabinoids, with the exception of hemp as defined in RCW 15.140.020.”

- Nordhorn said the bill would add the following definitions:

- Stakeholders asked a variety of questions and offered remarks about the privileges, definitions, and intent of the proposal.

- Amber Wise, Medicine Creek Analytics Science Director, brought up traceability, curious how “cannabinoids from outside” would be documented in the Cannabis Central Reporting System (CCRS) being implemented by the end of the year “or existing reporting system.” Nordhorn answered that the bill wouldn’t address an “operational issue” like compliance reporting, but expected licensees would “follow the same type of approach that the CBD cannabinoid has right now” (audio - 2m, video).

- Wise was a panelist at the June 3rd deliberative dialogue.

- The CCRS was last discussed by WSLCB staff on September 8th. A second webinar on the system was scheduled for October 4th and the event announcement stated, “All questions must be received no later than September 29, 2021.”

- Sarah Ross-Viles, Public Health - Seattle & King County Youth Health and Marijuana Program Manager and Washington State Legislative Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis Disproportionately Impacted Communities Work Group member, asked about the “practical outcomes” of the draft bill. Would the law require a rulemaking period, she wondered, or “an automatic clearing from sale of psychotropic and impairing substances” until rules were established? (audio - 3m, video)

- Policy and Rules Manager Kathy Hoffman was certain rulemaking would be required due to a new law, as definitions set a “framework” for establishing rule.

- Director of Legislative Relations Chris Thompson added that, as drafted, the bill would take effect on July 1st in 2022, before “any possibility that rulemaking would be completed.” He speculated on some “operative legal provisions that would be in force as of July 1...the prohibition on artificial cannabinoids for instance, but much of the, the detail would only be worked out in rule” likely finished “well beyond” the effective date.

- Ross-Viles later returned to her comment on “bringing all psychotropic and impairing cannabinoids into the regulated market process.” She asked staff to revise the bill language to “just be very clear that these products are not allowed outside of the regulated market” as soon as the legislation took effect “given that these products are currently being sold outside the...regulated market, perhaps preventing the biggest public health risk at this time” (audio - 1m, video).

- Brooke Davies, Washington CannaBusiness Association (WACA) Deputy Director and Associate Lobbyist, inquired if it was the intent of agency representatives to ban “synthetic D8 or D9.” As the revised definition for processors “says these are the allowable things a processor can do and then references the additives section,” RCW 69.50.326---where she noted language specifically said ‘only nonpsychotropic cannabinoids’---she wanted to know if staff intended to ban “hemp-derived THC from” the regulated system (audio - 2m, video).

- Nordhorn replied that the intent was to create “allowances” for producers “that are also growing hemp...in the I-502 marketplace.” If cannabis was “being grown and coming through the system then we want to afford opportunities to be able to do some of...the type of conversions of those products.” But imported hemp biomass “trying to be introduced into the system as THC” wouldn’t be allowed under the bill.

- Davies later commented that WACA members had discussed the topic and “done a lot of voting on it” as part of a “comprehensive survey.” The position of the group was that “all forms of THC...should have a path to be included in the regulated marketplace,” as it would be safer than letting them remain the domain of “the gray market, in the illicit market.” Given the changes to RCW 69.50.326, Davies found WSLCB staff had “raised the bar for testing requirements for non-psychotropic cannabinoids” and, with those restrictions, she speculated staff could develop a “regulatory framework to also make sure that hemp-derived THC from outside of the 502 system is safe as well” (audio - 2m, video).

- AJ Sanders, a Spokane Regional Health District (SRHD) Health Program Specialist, wanted to know if “all psychotropic cannabinoids would be sold only within the licensed 502 stores, not in a convenience store, for example.” Hoffman affirmed all such products would be under the regulation of WSLCB (audio - 1m, video).

- Sanders helped lead the SRHD “Weed to Know” campaign, which was presented at the WSLCB Prevention Roundtable on June 3rd.

- Trecia Ehrlich, Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) Hemp Program Manager, offered a concern “about how psychotropic will be defined” as it was her understanding that “CBD could be psychotropic in the sense that it impacts your brain.” She noted other drugs with psychotropic effects that weren’t impairing. Nordhorn responded that staff understanding of the term psychotropic “relates to the impairing effect on the brain, whereas ‘psychoactive’ can impact the brain, but it’s not necessarily impairing.” Psychoactive compounds were “what we’re not trying to address in this,” he said, but “anything leading into” impairment would be covered. Nordhorn added that this wording had been suggested “from some of the scientists” (audio - 2m, video).

- Ehrlich returned to this topic in later comments, saying that without additional definitions, it was unclear to her “how this will affect some CBD products.” Moreover, she found that many varieties of cannabinoids hadn’t been “well studied for impairment, there might not be any data that says that they produce impairment.” She was apprehensive about setting firm limits in the event “the federal landscape changes.” Ehrlich also pointed out some hemp producers in the state grew “smokable hemp flower” below 0.3% THC and she wasn’t sure how their products would be impacted by the draft request legislation (audio - 1m, video).

- Shawn DeNae Wagenseller, Washington Bud Company Co-Owner, quoted “section [1](3) of the 2013 intentions of I-502” which aimed to place cannabis “under a tightly regulated, state-licensed system similar to that for controlling hard alcohol.” As producers “don’t grow just THC, we grow everything that the plant grows” including “minor cannabinoids,” they could provide those compounds “as additives.” She wondered how any cannabinoids produced from “outside the system” would comport with “the intent of I-502,” adding a concern that they might be sourced from “illegal organizations” (audio - 6m, video).

- Nordhorn asserted, “I don’t think we can go back to 2013 and heavily rely on the overall intent portion” since state legislators had legislated imported CBD from “an unregulated source” for use in legal products. Doubling down on an alleged “legislative interest in allowing the non-psychotropic type of product” into the marketplace “as an additive,” Nordhorn commented, “if the law allows the one, why wouldn’t it allow for others?”

- Thompson noted the law, HB 2334, was passed in 2018 and focused on allowing CBD “to be added to marijuana products from within the system, or if tested, from outside the system.” With that legislative precedent, he presumed the law was “a reflection of interest from industry and consumers, and...a reflection of some of the innovation that we see in the industry.” Thompson stated staff were “mindful of” the intent of I-502, but the draft request bill was “modeled on the legislature’s prior decision on CBD...and we’re raising the bar here” with “new, expanded, more rigorous testing requirements.”

- Hoffman brought up “I-502 and harm reduction, and making sure that these products that are finding their way into the system now that are unregulated are tested to reduce the harms that we’re now seeing.”

- Wagenseller subsequently remarked that the intent of voters with I-502 was to “highly regulate this plant and the sale of this plant and us licensed growers” produced “all the cannabinoids.” She viewed this proposal as “opening up a wide path to support the hemp industry coming into our system” and favored hemp-derived cannabinoids. Wagenseller speculated that the result could be to “absolutely squash innovation of genetic breeding to breed plants that are high in CBD or high in CBG.” She suggested growing practices that had produced high-CBD cannabis could be used to produce cultivars with prominent cannabinoids besides THC. The proposal would instead “hand over all the other cannabinoids to unregulated plants.” Wagonseller preferred something that would “close the door for CBD and not open it wider” (audio - 2m, video).

- Bonny Jo Peterson, Industrial Hemp Association of Washington (IHEMPWA) Executive Director, echoed Ehrlich’s remarks on defining psychotropic as it was “used interchangeably with impairing and it doesn’t seem like that’s exactly consistent.” Turning to required testing, she said the proposed definitions didn’t mention “residual solvents or microbial” tests and that if the intention was to allow for delta-8-THC made by “changing the molecular structure” of CBD, then regulators needed to bear in mind that these changes were done though processes with “damaging, and well, destructive solvents.” She wondered if testing for this would be added or could be included (audio - 3m, video).

- Hoffman explained that all products had to pass “the I-502 suite of tests” before being sold to consumers regardless of their cannabinoid additives and mentioned the ongoing Quality Control Testing and Product Requirements rulemaking project which might eventually add pesticide testing “to that suite of tests.”

- Thompson sought clarification from Peterson as to whether she was asking agency representatives to “introduce a definition of ‘psychotropic’ or ‘impairing’ or both” through legislation or WSLCB rulemaking. Peterson confirmed this interpretation, and Hoffman said staff intended to define the terms (audio - 1m, video).

- Peterson later asked how the proposal could impact “full-spectrum” hemp products “that [have] all of the benefits of the plant.” Even though “the definition of CBD product is very specific,” it could change due to federal regulations, she remarked. Hoffman replied to say that adding a definition for “full spectrum” was a possibility (audio - 2m, video).

- Mark Tegen, Executive Director of Engineering for clēēn:tech, asked WSLCB officials to consider regulating “non-psychotropics” in the cannabis plant as well, suggesting that compounds like CBN were “almost entirely made synthetically today.” He also suggested the agency establish a “minimum purity or potency” level, since “the unknowns seem to be the issue” (audio - 2m, video).

- clēēn:tech President Marcus Charles addressed the board on his company’s work around synthesized cannabinoids on May 26th and June 9th. A video published on the company website claims they leased “technology to regulated producers and processors around the world on a subscription basis.”

- Kent Haehl, Atlas Group and Atlas Global Technologies LLC President, commended WSLCB staff for “significant progress” on the topic. He sought confirmation that “CBD from outside the market can be brought in as long as it meets the definition of a hemp product” and was an option “on the table.” Haehl was also curious whether WSLCB leaders were “saying that a product that...its legal status would potentially be affected favorably by this legislation passing, that a product that could pass the current I-502 suite of tests would be considered safe” (audio - 4m, video).

- Hoffman called that “a fair statement,” and Thompson reiterated that there would be “new testing requirements” for such products, not “exactly” the system already in place for CBD. Nordhorn added that the draft focused on cannabinoids other than CBD coming into the legal cannabis system “but, only to be used as an additive.” This meant that CBD from outside the I-502 system “couldn’t then be converted into THC at a later state, they could only be used as an additive.”

- Haehl looked for clarification on whether agency representatives were saying “CBD isolate, providing it can pass all of the testing, is available to be used in the marketplace as an additive only. Are we saying that CBD isolate sourced from inside the state of Washington from a hemp farmer or a licensed marijuana producer, that would be allowed to be converted into THC, as in treated differently than something coming in from outside the state?” Nordhorn said “the short answer is yes,” as the goal of regulators was to allow innovation “in the tightly controlled and regulated structure, if we have a licensed producer who’s also growing hemp” and wants to incorporate CBD from hemp into cannabis items “we’re trying to set up a pathway for that to occur.” He made clear they were not trying to allow “creating the impairing substance from outside of the regulated marketplace.” Nordhorn noted that a WSDA licensed hemp grower would “not have the same privileges that a licensed marijuana producer has” (audio - 3m, video).

- Haehl’s LinkedIn profile said his company helps manage a “portfolio of regulated and ancillary cannabis and hemp business units including...Unicorn Brands.” On July 7th, Haehl confirmed that the company had engaged in cannabinoid synthesis to make as much as “200 liters of distilled oil per month” before the practice was formally prohibited on July 22nd.

- Wagenseller referred to section 4 of the proposed request bill where both producers and processors were permitted to “use CBD, other nonpsychotropic cannabinoids, or a nonpsychotropic plant Cannabis isolate” for the purpose “enhancing the nonpsychotropic cannabinoid concentration.” Finding the passage confusing, she said her impression had been that producers could “only grow plants” and couldn’t “process, or enhance, or make a product that’s ready for the market, only processors can do that.” Could producers “bring in 95% pure isolates of minor cannabinoids and utilize them to enhance the product before it goes on to processing?” Wagenseller wondered, “that just completely confuses me” (audio - 3m, video).

- Nordhorn responded that though they weren’t trying to change the “full structure” of producer licenses, there were “a number of folks out there that hold a producer/processor license.” In trying to make the “system flow to work appropriately,” staff also sought to preclude “product coming from outside of the 502 system be used as an additive to a product and then converted into...another impairing cannabinoid.” He asked Wagenseller to put her concerns in writing so staff could better review the draft legislation

- The following people requested to speak but were unable to participate when offered the chance. Staff encouraged any further remarks to be submitted in writing to rules@lcb.wa.gov.

- Hailey Croci, American Lung Association Tobacco Control Coordinator and a representative of TOGETHER! for Youth in Chelan-Douglas Counties

- Sierra Williams, Assistant Attorney General in the Division of Agriculture and Health at the Washington State Office of the Attorney General (WA OAG)

- Gregory Foster, Cannabis Observer Founder + Citizen Observer

- During the webinar, Foster emailed WSLCB staff presenters the following question: “Following on Ms. Ehrlich's and Ms. Peterson's comment, I agree ‘psychotropic’ and ‘impairing’ should be defined. How would the hundreds of cannabinoids, terpenes, flavonoids, and other compounds produced by the plant be measured or declared as psychotropic or impairing?”

- At publication time, Foster had not received acknowledgment nor a response to his email.

- Amber Wise, Medicine Creek Analytics Science Director, brought up traceability, curious how “cannabinoids from outside” would be documented in the Cannabis Central Reporting System (CCRS) being implemented by the end of the year “or existing reporting system.” Nordhorn answered that the bill wouldn’t address an “operational issue” like compliance reporting, but expected licensees would “follow the same type of approach that the CBD cannabinoid has right now” (audio - 2m, video).

Information Set

-

Announcement - v1 (Sep 24, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Handout - Agency Request Legislation - Cannabinoid Regulation (Sep 20, 2021) [ Info ]

-

WSLCB - 2021-22 - Agency Request Legislation - Psychotropic Compounds

[ InfoSet ]

-

Bill Text - Z-0334.1 (Sep 1, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Announcement - Stakeholder Feedback Invited (Sep 1, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Announcement - More Time for Stakeholder Feedback (Sep 7, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Bill Text - Z-0334.2 (Sep 10, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Announcement - Webinar Details (Sep 24, 2021) [ Info ]

-

-

Complete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Complete (1h 26m 11s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Welcome - Chris Thompson (4m 20s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Background - Justin Nordhorn (13m 9s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Draft Legislation - Justin Nordhorn (16m 48s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 04 - Questions and Answers (3m 17s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Question - Traceability - Amber Wise (2m 8s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 06 - Question - Effective Date - Sarah Ross-Viles (2m 45s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Question - Hemp Biomass THC - Brooke Davies (1m 57s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Question - Retail Sales - AJ Sanders (57s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 09 - Comment - Mark Tegen (2m; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 10 - Question - Psychotropic and Impairing - Trecia Ehrlich (2m 16s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 11 - Question - 502 Intent - Shawn DeNae Wagenseller (5m 59s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 12 - Question - Psychotropic and Impairing - Gregory Foster (57s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Question - Testing Requirements - Bonny Jo Peterson (2m 45s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 15 - Question - Sierra McWilliams (40s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 16 - Question - Hailey Croci (20s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 17 - General Comments - Kathy Hoffman (1m 21s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 18 - Comment - Hailey Croci (11s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 19 - Comment - Kent Haehl (3m 43s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 20 - Comment - Brooke Davies (1m 42s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 21 - Comment - Trecia Ehrlich (1m 29s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Comment - Shawn DeNae Wagenseller (2m 12s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 23 - Comment - Kent Haehl (2m 54s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 24 - Comment - Shawn DeNae Wagenseller (2m 59s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 25 - Comment - Hailey Croci (46s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 26 - Comment - Sarah Ross-Viles (1m 25s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 27 - Comment - Bonny Jo Peterson (1m 48s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 28 - Wrapping Up - Katherine Hoffman (55s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Wrapping Up - Justin Nordhorn (57s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 30 - Wrapping Up - Chris Thompson (2m 26s; Sep 27, 2021) [ Info ]

-