The influence of prevention organizations on WSLCB policy was the focus of a presentation from the agency’s public health liaison and remarks from Cannabis Advisory Council members.

Here are some observations from the Wednesday January 6th Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (WSLCB) Cannabis Advisory Council (CAC) meeting.

My top 3 takeaways:

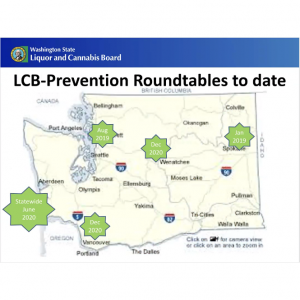

- WSLCB leadership organized a series of closed roundtable events with substance use prevention advocates around the state to train them on agency processes and to hear policy perspectives from “prevention and public health partners.”

- Cannabis Observer began tracking the prevention roundtables in August 2019. Outgoing Board Chair Jane Rushford and eight staff members represented the agency at that event.

- In July 2020 during a scheduling update, agency staff talked about planning more “prevention roundtables and outreach” in relation to the annual Washington State Prevention Summit (audio - 5m).

- In the fall, prevention professionals offered public comment during WSLCB board meetings in August, September, and October 2020 to voice perspectives and concerns.

- In December 2020 when Public Health Education Liaison Sara Cooley Broschart briefed agency leadership, she said “many individuals brought up” concerns about temporary policy allowances granted to cannabis and alcohol licensees due to coronavirus restrictions. She noted two more virtual roundtables would be hosted on December 17th and 18th (audio - 13m).

- Cannabis Observer registered to attend the December events but learned they were closed to the public and only open to individuals affiliated with prevention or public health organizations.

- See Broschart’s presentation from the December 17th roundtable obtained via public records request.

- During a board caucus on January 12th, Rushford highlighted the agency’s engagement with prevention organizations which were “really learning how to work with us and they’re participating more and more often” (audio - 1m).

- At the January 13th Executive Management Team meeting, WSLCB Director of Legislative Relations Chris Thompson described the development of agency request legislation to "extend, temporarily, some of the privileges granted to liquor licensees during the pandemic" through July 1, 2024. The request bill, prompted by outreach from the Office of the Governor, would more permanently encode curbside delivery and to-go cocktails while including a "study reviewing the impact of this extension." Prevention stakeholders had voiced interest in the study but were “somewhat to vehemently opposed” to expanding alcohol privileges in statute (audio - 8m).

- In advance of the January 6th Cannabis Advisory Council (CAC) meeting where I serve as the consumer representative, I suggested an agenda item to discuss inviting a CAC member to future roundtables.

- CAC members also discussed council membership and the 2021 legislative session during the January 6th meeting.

- Other public health and prevention events in the months before the CAC meeting:

- In September 2020, Washington State Health Care Authority (WA HCA) staff hosted a webinar on impacts of cannabis legalization.

- In October 2020, the Northwest Prevention Technology Transfer Center (NW PTTC) hosted a webinar on the pharmacology of cannabis.

- On November 12th at the request of WA HCA, WSLCB staff led an Advocacy and Rulemaking webinar. When asked about the then-recently formed Cannabis Regulators Association (CANNRA), Policy and Rules Manager Kathy Hoffman indicated Broschart was advancing a youth cannabis use prevention message through the organization (audio - 2m).

- At publication time, WSLCB Director Rick Garza was the First Vice President of CANNRA.

- On November 4th, NW PTTC Co-Directors Kevin Haggerty and Brittany Cooper led a session at the Washington State Prevention Summit addressing A Couple of Things About Cannabis.

- On December 9th, Washington Poison Center (WAPC) representatives hosted an education course titled Let's Talk Cannabis.

- On December 17th, NW PTTC facilitated a discussion on cannabinoid concentration research titled The More the Merrier?

- On January 5th, the Prevention Voices coalition requested a class from the Washington State Legislative Information Center (WA LIC) and organized a pre-session summit on January 7th.

- At the CAC meeting, Public Health Education Liaison Sara Cooley Broschart described her “unique” position at WSLCB and discussed the recent roundtables.

- Broschart took time to “talk about what my role is” at the agency as well as speaking to “some interest from folks” on the roundtables (audio - 8m).

- Broschart replaced Mary Segawa as the Public Health Education Liaison in April 2019, “a really unique position” for “a public health person” which “very, very few of the other regulatory agencies in other states have.” Broschart claimed her work helped WSLCB in “understanding impacts...of the substances we regulate to health and the community.” She felt that ‘liaison’ was an apt title for “what my role is.”

- Immediately before Broschart joined WSLCB, Scott McCarty was introduced as Segawa’s replacement but left the agency shortly thereafter. Broschart’s hiring was first mentioned in March 2019.

- Broschart felt WSLCB staff “hear so much from the folks we regulate, you all, and others, but the public health stakeholders are often off doing their own thing.” This meant the “particularity of me being able to liaise with them, kind of meeting them where they’re at, is part of the role,” she said.

- Broschart represented the agency “on alcohol, cannabis, and vapor at the state and national level” in addition to sharing “the status of education and prevention programs with the Board and senior agency management.” She aimed to help increase “knowledge of agency, board, and staff regarding public health” for “agency decision making.”

- Broschart replaced Mary Segawa as the Public Health Education Liaison in April 2019, “a really unique position” for “a public health person” which “very, very few of the other regulatory agencies in other states have.” Broschart claimed her work helped WSLCB in “understanding impacts...of the substances we regulate to health and the community.” She felt that ‘liaison’ was an apt title for “what my role is.”

- Broschart said “a couple years back” a suggestion was put forward to host prevention outreach events and she chose the description “roundtable” as the gatherings were “a little bit more” informal.

- At the events, staff conversed with prevention organization representatives, to “learn from each other, and kind of share.” Broschart showed a slide describing goals for the events such as building relationships between agency leadership and the “prevention/public health community,” addressing regional concerns, and allowing advocates to “share experiences, input, and/or knowledge.” She noted that these stakeholders were “not a part of a council such as this one” and had “many, many things on their plate.”

- Roundtables gave the prevention groups “a moment to pause and really hear from each other,” Broschart explained to the Council, and helped advocates stay “connected with” the agency. She created “a regular mechanism” to host events “twice a year” in “two different regions each time.”

- Broschart said that in 2019 two in-person roundtables were held, first in January in Spokane, and then in August in Bothell to coincide with the Board’s public meetings in those areas.

- In 2020, even though things were “shaken up” by the pandemic, June and December roundtables focused on central Washington, “Wenatchee, Ellensburg, and north of there,” and southwest Washington, as well as a summer event that was part of the statewide Prevention Summit, she commented.

- For 2021, dates were not finalized but Broschart expected consideration would be given to prevention groups in “the [Olympic] peninsula” and southeast Washington.

- The topics and takeaways Broschart identified from the roundtables included “regional enforcement updates” and concerns, training on engagement with the agency, collaborative discussions, and “presentations by public health/prevention partners to us...be it data or otherwise.”

- Broschart explained that WSLCB “always did [a] survey” of attendees “to see what the interests of the local prevention and public health partners would be” so that staff could speak to “what they wanted to hear from us.” Broschart told the Council that she had fielded requests “to hear about marijuana advertising...and then, of course, COVID-19 alcohol and marijuana allowances and what that’s looking like.”

- She said roundtables had evolved to include regional prevention organizations as “a part of planning” and that advocates worked with Broschart during several “planning calls” ahead of the meetings “and really, also, focusing on what they wanted to share with” her and agency leadership. The roundtables were “a two way communication point,” she said.

- Broschart told the Council members she found it ”interesting” how prevention groups “may be working with you all.” She cited the Vancouver-based Prevent Coalition’s “Secure Your Cannabis campaign” which featured “high level messaging” on safe storage and conversations with kids discouraging “underage cannabis use.” Broschart said there was interest from prevention groups “to bring some of you into this idea” and the campaign exemplified a “great partnership that we can find of prevention folks with licensees.”

- Broschart took time to “talk about what my role is” at the agency as well as speaking to “some interest from folks” on the roundtables (audio - 8m).

- Broschart then invited questions and comments from the Council, receiving feedback encouraging greater transparency into the agency’s association with prevention stakeholders and recommendations going forward.

- Caitlein Ryan, Interim Executive Director and Board President of The Cannabis Alliance, reported that she had “registered for the roundtable” because her organization was “involved in partnerships exactly like the one that you’ve described.” However, “the evening before the meeting I was told I was not allowed to attend,” she said, raising an “issue of transparency that I know LCB has been endeavoring to correct.” Ryan felt “collaborative efforts” were crucial “to the prevention community reaching their goals” noting the “collaborative success” between the industry and prevention advocates in packaging and labeling rulemaking during 2019. She “strongly” advised inclusion of the cannabis sector in future roundtables to avoid a perception that WSLCB was “functioning as a gatekeeper to keep these two entities apart from one another” (audio - 3m).

- Broschart regretted “that was the perception, that was not the intent,” saying the agency met with various stakeholders to be able to “focus on the concerns of that particular body” but that WSLCB would “welcome” more partnerships. She told Ryan she could “bring you two together apart from the roundtables” which had “their explicit purpose,” but that “we’d all like to see more collaboration across all fronts.” Ryan replied that the Cannabis Alliance “already had that connection...but as LCB you are an official host” of the private meetings. She requested the agency then organize “opportunities for our whole industry and prevention to get together...that would be a wonderful goal for LCB.”

- Bailey Hirschburg, the Council’s consumer representative from the Washington chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (WA NORML), told the Board that prevention roundtables would “be improved by inclusion of a CAC representative going forward” (audio - 3m, written comments).

- He argued that WSLCB was arranging events where a collection of groups provided “a message to the agency, but they’re also about influencing policy.” Hirschburg said as a citizen observer he’d found numerous events “geared towards the prevention community that are hosted by state agencies.” However, he remarked, roundtables were the first meetings he had encountered which were shielded from the public and “closed...to prevention partners.”

- Hirschburg did “kind of respect” that “not every meeting at the agency is going to be open, but I think one of the ways we negotiate that” would be to include a council member at subsequent roundtables. He said, “It increases transparency for us” while giving “better feedback” to roundtable attendees whose concerns went beyond regulatory to “legislative questions and questions on industry practices or behavior.” CAC involvement made it more likely “there’s someone there who can speak to those” inquiries, he reasoned, and “gives us a better idea what their agenda is” while avoiding “siloing off” stakeholder information.

- Hirschburg felt another distinction was that prevention advocates currently had “a staff person at the agency who liaisons with them” to provide their “opinion to the public and to, you know, the leadership of LCB.”

- Respectful for prevention groups’ “privacy to have that dialogue,” he remained “troubled,” feeling there were “ways to improve” the roundtables. Broadly, Hirschburg viewed CAC participation as “building inroads” among stakeholders while keeping agendas for roundtables “focused on public health issues” rather than being an overbroad “mix of the two stakeholders.”

- Lukas Barfield, patient CAC representative and member of the Tacoma Area Commission on Disabilities, called attention to the fact that Washington was among the only states to have “a position like this” but that didn’t “necessarily make it a good thing” (audio - 2m).

- He said that available information supported the view that underage use “has not gone up since cannabis legalization” and there was data supporting “incredible health benefits from medical cannabis.” Barfield said he backed “increased access for medical cannabis” in Washington and wondered if WSLCB could “produce empirical data to actually show that we actually need a position like” Broschart’s. He was surprised that there were “tax dollars spent on this” and that while Washington pulled in “a lot of tax dollars from” legal cannabis, regulators had “secret meetings with prevention people around the state trying to prevent people from getting cannabis.”

- Barfield called roundtables “an odd situation” and though he supported education around safe cannabis storage he maintained that “on some of these public health outcomes we have study after study that is showing that cannabis is not having a negative effect.” He closed on a note of skepticism asking why an agency regulating adult and patient cannabis access would “need this, this position...as far as cannabis goes”

- Jeremy Moberg, representing the Washington SunGrowers Industry Association (WSIA), appreciated the update, saying he did “believe that there is the potential for harm” to minors and cannabis consumers around “very high potency concentrates” (audio - 1m).

- Moberg said that concentrates were “becoming cheaper and cheaper” and were “fully obfuscated” by way of “synthesized cannabinoids coming in from the hemp market.” Moberg was curious if prevention organizations had “an opinion on the state of overproduction and what that potentially leads to” insofar as “cheap access to very high concentrations” in products. He hoped that prevention professionals connected “overproduction” and affordable cannabis concentrates.

- Hirschburg replied that prevention leaders at events he’d covered “certainly have sounded concerned about” product potency even if they weren’t “aligning it with that industry practice.” He described prevention advocates’ interest in legislation similar to Representative Lauren Davis’ bill limiting cannabinoid concentrations, HB 2546, which was criticized during a January 2020 public hearing. Hirschburg believed that prohibiting items was equivalent to admitting “I only want this cannabis product available in the illicit market.” If prevention organizations did “want to look at how we label cannabis concentrates, how we package them, and how they’re available to the public,” he encouraged them to consider what items they’d “only want available illicitly” if they were removed from the legal market (audio - 1m).

- Moberg said that concentrates were “becoming cheaper and cheaper” and were “fully obfuscated” by way of “synthesized cannabinoids coming in from the hemp market.” Moberg was curious if prevention organizations had “an opinion on the state of overproduction and what that potentially leads to” insofar as “cheap access to very high concentrations” in products. He hoped that prevention professionals connected “overproduction” and affordable cannabis concentrates.

- Caitlein Ryan, Interim Executive Director and Board President of The Cannabis Alliance, reported that she had “registered for the roundtable” because her organization was “involved in partnerships exactly like the one that you’ve described.” However, “the evening before the meeting I was told I was not allowed to attend,” she said, raising an “issue of transparency that I know LCB has been endeavoring to correct.” Ryan felt “collaborative efforts” were crucial “to the prevention community reaching their goals” noting the “collaborative success” between the industry and prevention advocates in packaging and labeling rulemaking during 2019. She “strongly” advised inclusion of the cannabis sector in future roundtables to avoid a perception that WSLCB was “functioning as a gatekeeper to keep these two entities apart from one another” (audio - 3m).

Information Set

-

Agenda - v0 [ Info ]

-

Agenda - v1 [ Info ]

-

Complete Audio - Cannabis Observer

[ InfoSet ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 00 - Complete (2h 4m 54s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 01 - Welcome - Ollie Garrett (1m 17s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 02 - Introductions (5m 53s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 03 - Updates - Public Health and Prevention - Sara Cooley Broschart (8m 22s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 05 - Updates - Public Health and Prevention - Question - Caitlein Ryan (3m 14s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 06 - Updates - Public Health and Prevention - Comment - Bailey Hirschburg (3m 11s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 07 - Updates - Public Health and Prevention - Comment - Lukas Barfield (2m 17s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 08 - Updates - Public Health and Prevention - Comment - Jeremy Moberg (1m 25s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 10 - Interpretive and Policy Statement Program - Kathy Hoffman (7m 22s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 13 - Interpretive and Policy Statement Program - Question - Jeremy Moberg (2m 56s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 17 - Rulemaking Updates - Tier 1 Expansion - Casey Schaufler (2m 41s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 18 - Updates - Enforcement and Education - Justin Nordhorn (11m 4s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 19 - Updates - Enforcement and Education - Question - Brooke Davies (2m 29s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 20 - Updates - Enforcement and Education - Comment - Jeremy Moberg (2m 22s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 21 - Updates - Enforcement and Education - Question - Bailey Hirschburg (2m 33s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 22 - Updates - Enforcement and Education - Question - Caitlein Ryan (4m 27s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 23 - Updates - WA Task Force on Social Equity in Cannabis - Ollie Garrett (4m 16s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 26 - Updates - Technology - SMP - Megan Duffy (1m 35s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 27 - Updates - Technology - Traceability - Megan Duffy (1m 34s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 28 - Updates - Rick Garza (27s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 29 - Updates - Budget - Rick Garza (3m 1s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 30 - Updates - Hilliard and Heintze Outcomes - Rick Garza (9m 34s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 31 - Updates - Question - Bailey Hirschburg (1m 56s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 32 - Updates - Question - Lukas Barfield (5m 27s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 33 - Updates - 2021 Legislative Session - Chris Thompson (4m 2s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 34 - Updates - 2021 Legislative Session - Question - Bailey Hirschburg (1m 5s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 35 - Updates - Washington CannaBusiness Association - Brooke Davies (2m 2s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 36 - Updates - The Cannabis Alliance - Caitlein Ryan (5m 39s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 37 - Updates - Washington SunGrowers Industry Association - Jeremy Moberg (7m 21s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 38 - Updates - Craft Cannabis Coalition - Joanna Monroe (1m 42s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 39 - Updates - Consumer Representative - Bailey Hirschburg (1m 15s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 40 - Updates - Ollie Garrett (2m 46s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 41 - Updates - Patient Representative - Lukas Barfield (2m 57s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-

Audio - Cannabis Observer - 42 - Wrapping Up - Ollie Garrett (24s; Jan 6, 2021) [ Info ]

-